Imagine taking a test to prove your proficiency in a language you’ve been fluent in your whole life — and paying a hefty sum on top of it. That’s the reality of many international students who have to fork out a great deal of money to pay for English proficiency tests in order to apply for universities abroad.

Take the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), for instance. The fee for the academic IELTS varies from country to country; in the UK, for instance, fees start from 175 pounds, which can be exorbitant for students from developing countries with lower currency rates. Nigerian students have been campaigning for universities to scrap the IELTS for their university entry, even going as far as starting a petition on Change.org.

IELTS is pure extortion.

Nigeria with English as its lingua Franca should not be mandated to write IELTS before working or schooling in the U.K.

it makes no sense at all.I took up a job in the UK and I didn’t have communication issues even without IELTS#ReformIELTSPolicy

— General Okwulu Okalisia (@RapidMax01) January 26, 2022

Presently, the UK Home Office has only waived the IELTS test for citizens of 18 countries where English is adopted as an official language. Yet, it is also widely taught at all levels of education in Commonwealth countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, India, and Malaysia. Students coming from these countries must produce an acceptable level of English at the application stage before they can be considered for admission.

English proficiency tests: Fair for international students?

Much of the furore surrounding mandatory English proficiency exams is due to the unreasonable fees charged for a single test. The Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) — another popular English proficiency exam — doesn’t have a fixed price and varies by location. In India, for example, the TOEFL can cost from 190 US dollars. Additional charges apply for late registration, rescheduling, and extra score reports, which adds to international students’ financial burden.

To complicate matters further, the IELTS and TOEFL have a two-year validity date. Once it expires, the test scores cannot be used for future applications, and students have to retake the exam even if they did well the first time.

“I personally believe that it’s a crime for the English proficiency tests in English-speaking countries especially knowing that they cost up to US$250 (three times the minimum wage in Nigeria),” said Ebenezar Wikina, a critical voice behind the #ReformIELTSPolicy movement, in a previous interview with Study International.

“This means if I take the IELTS to study in Australia before I graduate from my bachelor’s programme, my first IELTS would have expired and I would have to prove it once again by paying another US$250,” he said.

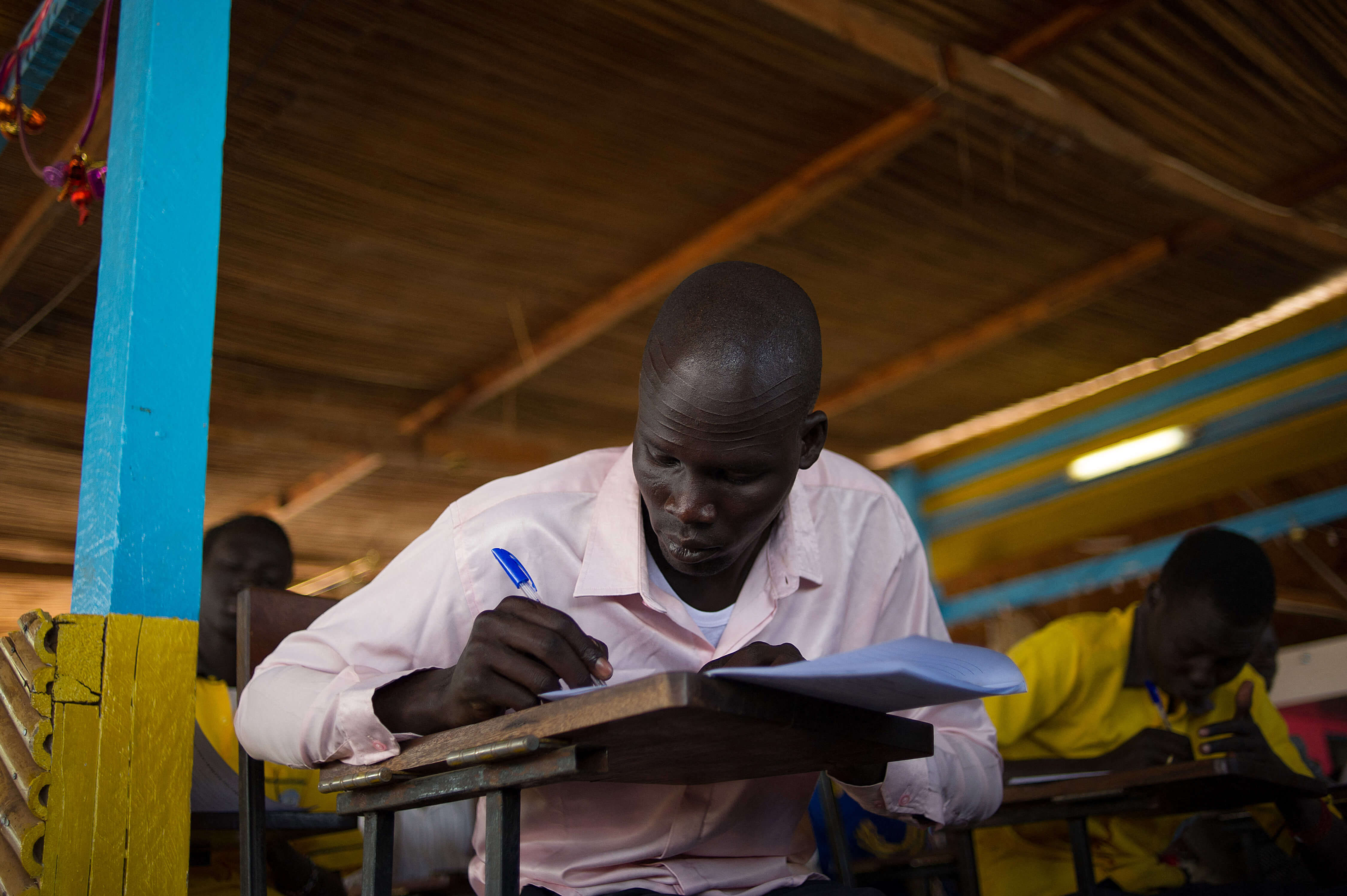

Some have accused the English proficiency test business as a profit-driven industry instead of truly measuring a user’s fluency in the language. Source: Phil Moore/AFP

International students already face near-insurmountable barriers with skyrocketing tuition fees, and that’s not including other costs involved in studying abroad, such as visa applications and flight tickets. Some argue that the necessity for English proficiency tests is motivated by revenue rather than linguistic fluency.

With three million test-takers yearly, IELTS is known to be a lucrative business. IELTS’ co-owner IDP generated revenue of nearly 487 million Australian dollars in 2018, said a report.

“It should be urgently reviewed as there are flaws in this system. Why are we forcing migrants to sit in this test again and again? I wonder how your English can expire,” said Navdeep Singh, member of the Greens Senate political party in Australia, to SBS Punjabi when commenting on the testing system used to gauge English language proficiency among migrants.

While concerns over incoming students’ fluency in English at the academic level is valid, limitations still exist with standardised testing to fully indicate a student’s full range of abilities.

Alternative tests, such as an internal examination administered by universities, or accepting past transcripts where English was taught at the secondary level, could make things easier for international students.

“A change in the policy would make life easier for Nigerian students who wish to study abroad or access opportunities because now the ultimate English proficiency barrier has been removed,” said Wikina in a separate interview.