It is 2017. The US Department of Justice announces that more than US$4.5 billion was syphoned by a few powerful individuals from the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) fund — a sovereign wealth fund meant to help alleviate poverty — to buy luxury real estate, a private jet, Van Gogh and Monet artworks, finance Hollywood blockbuster “The Wolf of Wall Street”, and hoard 272 exclusive Hermès Birkin bags owned by the then-first lady of Malaysia Rosmah Mansor.

The wife of then-Prime Minister Najib Razak inflamed regular Malaysians when she allegedly bought a US$200,000 crocodile Birkin bag. It is the price of two three-bedroom apartments in the Malaysian capital or what the average Malaysian earns in 38 years.

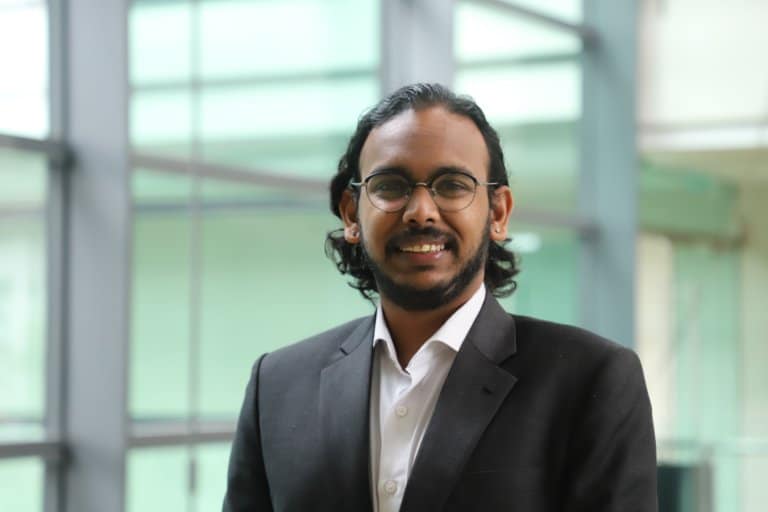

Where many simmered in anger, one fresh graduate from the University of Warwick sprung into action. Daniel Rajasingam Subramaniam became an aide to Democratic Action Party’s (DAP) Tony Pua, a member of the opposition who was vocal against former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s wrongdoings. “I had the chance to work with Tony Pua as a Special Officer after I graduated. At the time, Malaysia was seeing a lot of political fervour with the general elections due the following year,” Subramaniam tells Study International.

All smiles as political activist Subramaniam poses with Malaysian politician Yeo Bee Yin for the “Break Up with Plastics” video campaign. Source: Daniel Rajasingam Subramaniam

A budding interest forms into a passion

Although Subramaniam had been interested in politics since he was in school, he wanted to explore more subjects and did not fancy going into something so niche during his time abroad.

That changed after he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics from the University of Warwick. He was in the thick of it all after the ruling party lost the elections in 2018. Subramaniam found himself working for key figures leading Malaysia’s first-ever change of government.

“I was able to work for strong-willed politicians like Tony Pua and DAP’s Yeo Bee Yin, who were at the forefront of explaining the complexities of the scandal to ordinary Malaysians and drawing public attention to the issues of the day,” he says.

“It was the first time Malaysia saw a change in government, and there were a lot of new things to learn about the government administration, functions, and operations of the civil service. That experience really helped me see how policies are made, negotiated, and executed in the government.”

Subramaniam at the launching of the World Bank Report. Standing in the middle is finance minister Tengku Zafrul Aziz. Source: Daniel Rajasingam Subramaniam

‘Making politics accessible is key to a functioning democracy’

Widespread apathy drives Subramaniam. He can’t stand seeing young people uninterested and unwilling to vote. “I think that a lot of people get the sense that it is the big, immovable force and so they disengage from it,” he says. “But in reality, politics is part and parcel of our lives.”

“The area I’m most passionate about is helping people realise this and get involved. Making politics accessible is key to a functioning democracy because it ensures that people are engaged with questions that shape their lives and the country,” Subramaniam said.

He joined UNDI18, a youth-led project that aims to bridge the gap between politicians, policymakers, and youth. Once a student movement, the organisation successfully advocated for the amendment of Article 119(1) of the Federal Constitution, which reduces the minimum voting age from 21 to 18 years old in 2019 — the first time in history that a Constitutional Amendment received 100% of the votes in the Upper and Lower Houses of Parliament.

As soon as lockdown restrictions were lifted in his home country, Subramaniam was invited to join UNDI18 as a Programme Manager, where he led energy policy campaigns and conducted political education workshops.

“For me, the idea of expanding civic participation in governance has always been important. Governance is something that affects everyone, yet we often leave it to the domain of politicians and, increasingly, become jaded with the process,” he says. “UNDI18 offered not just the fundamental right to vote to young Malaysians but it also came at a time when there was strong public enthusiasm for change and reform.”

The political activist packed his bags and is now studying in Singapore. Source: Roslan Rahman/AFP

Taking his love for Malaysia a step further by studying in Singapore

Subramaniam was also a part of Closing The Gap, a programme that pairs mentors with mentees (bright but underrepresented students) to unlock their full potential and enrol in universities. Subramaniam volunteered to work with one mentee, who prefers not to be named, for over two years during the pandemic to help them prepare for post-high school plans.

Recalling how he chose to pursue an undergraduate degree in the UK, Subramaniam says, “I felt the UK undergraduate system suited me better with a focus on seminars and in-class discussions and the environment felt a bit more familiar compared to other countries abroad. Warwick was an easy pick as one of the top universities offering PPE. It was a really good opportunity to make friends and really explore life’s options, which, in my opinion, is one of the greatest things about university.”

For his master’s degree, Subramaniam chose to be closer to home. He’s now at the National University of Singapore‘s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy for what he calls more “pragmatic reasons”.

“I realised I had an interest in getting more involved in policy work. However, I lack research skills. That is what I am hoping to gain out of the Master in Public Policy,” he says.

After studying abroad not once, but twice in his life, Subramaniam learned that one should always be open to trying new things: “Studying abroad can appear daunting and applying to foreign schools is probably more so. What’s important is that you make the most of your time studying abroad.”