“Muslim migrant beats up Dutch boy on crutches!”

“Muslim Destroys a Statue of Virgin Mary!”

“Islamist mob pushes teenage boy off roof and beats him to death!”

These were the three videos shared by US President Donald Trump last November to his 43.6 million followers. Originally tweeted by ultranationalist group Britain First, they purportedly show regular Muslims committing acts of violence, without any context. In some cases, without any attempt at accuracy.

International outrage ensued.

One of the voices was Sadiq Khan, London’s mayor and the first Muslim to hold that position in a major European capital. In a tweet, Khan condemned Trump’s use of Twitter “to sow division and hatred in our country,” demanded an apology and asked for his upcoming visit to be canceled.

It was swift, decisive and very clear in stating racism has no place in London or the UK.

It’s the type of reaction Malaysian and Indonesian Muslim students in the UK hope more government figures and universities would emulate.

“I’m not so sure about the UK government as a whole, but as for London, I do see that the good mayor is doing a lot to stop any kind of Islamophobic and prejudicial attacks that are increasing nowadays, such as putting a lot more men on patrol,” Siti Aminah Muhammad Imran, a Malaysian PhD student at Imperial College London said.

Hate crime has no place in London & @metpoliceuk take a zero-tolerance approach. If you see a hate crime, report it. https://t.co/vfHbHJwXEu

— Sadiq Khan (@SadiqKhan) October 17, 2017

The city’s zero-tolerance approach to all forms of hate crime takes many forms: the #LondonIsOpen campaign, the introduction of specially-trained investigators to deal with hate crime in every London borough, the creation of an online hate crime hub to identify, prevent and investigate online abuse.

Beyond Khan and London, however, the fight against racial bigotry appears tepid, if it exists at all.

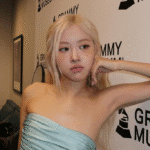

Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London carries flowers outside the Houses of Parliament on the anniversary of the terror attack in London. Source: Reuters/Peter Nicholls

Speaking to the BBC, Shakira Martin, the president of the National Union of Students called out UK universities’ poor performance in dealing with racism on campus. Commenting on the recent spate of racist abuse in several UK universities earlier this year, Martin said more needs to be done to make sure every student is safe on campus:

“They’re not prioritising it and taking it seriously … universities are more concerned about their reputation than the wellbeing of their students.”

“This is something that we need to tackle, not because it’s in the headlines of the media, but every student has the needs to be safe on campus.”

One way to do so could be through the creation of helplines on campus, suggests Qurratuain Ihsan, an Economics student at the University of Warwick. Aynn, as she wishes to be known, is grateful she’s never had to encounter an Islamophobic attack in the UK but told us she was the unfortunate victim of one in Europe. She now takes martial arts classes to learn how to defend herself better.

When asked what universities could do, Aynn said:

“For those who have experienced these incidents, the university should encourage them to go to a counselling session so that these incidents won’t affect their academic performance or wellbeing.”

Hate crimes cause lasting damage, both on the victim and their community. Beyond physical wounds, they can cause emotional harm on victims, through evoking despair, anger and anxiety.

When Putri was targeted for verbal racist abuse, it left her confused and disturbed. The overwhelming perception about Muslims is negative, she says, and universities can do more to counter this:

“I think they can start making an explicit statement about their stance against Islamophobia – not as a response to a particular incident, but as an initiative.”

A University of Edinburgh spokesperson said:

“The University is intent on promoting a positive culture for working and studying in which all members of the University’s community treat each other with dignity, respect and where inappropriate behaviour – including any form of discrimination, harassment and bullying – is handled accordingly. ”

“We would treat any claims of anti-Islamic sentiment on campus extremely seriously – should they arise – and act very swiftly if ever we are alerted to incidents of any kind.”

Failure to tackle racism towards Muslim students, including those from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Bangladesh, means isolating close to 10 percent of the international student population. Source: Shutterstock

A five-year study by the University of Sussex found empirical evidence that hate crimes leave “serious consequences” on communities as a whole. Simply knowing or reading a victim is enough to cause harm – making people feel vulnerable, anxious, angry or ashamed – and compelling them to change their behaviour such as avoiding certain situations or places where they may be more at risk of abuse.

A National Union of Students survey published this year found similar findings at the campus level. Muslim students are less likely to participate in the activities of or seek a high-profile position in their student unions. Two out of five respondents (43 percent) who reported having been affected by Prevent said this experience made it harder to express their opinions or views, especially on issues like racism, Islamophobia, Muslim student provision, terrorism, Palestine or Prevent.

Instead of preventing radicalisation, Shaffira Diraprana Gayatri, who graduated with a Masters in World Literature from the University of Warwick in 2015, believes the Prevent duty only serves to perpetuate Islamophobia and xenophobia.

“Academic institutions should be independent and protect their students, instead of unnecessarily putting teaching staff in an uncomfortable situation as a tool of the state, and causing students (especially Muslim students) to be paranoid and feel unsafe in their own campus,” Shaffira said.

Malaysian and Indonesian students make up more than 20,000 of the international student body in the UK. Failure to tackle racism towards Muslim students, including those from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Bangladesh, means isolating close to 10 percent of the international student population.

Shaffira remembers how then-Home Office secretary Theresa May’s strict immigration policies – regarding visa length, visa requirements, ease to get work post-study – added to feelings of antagonism felt. These policies, in addition to the Prevent duty and growing anti-Muslim sentiment, are “bad news” and can be costly for UK universities in the long run, she says.

“From my experience, it’s important for UK universities to make their students (in this case, especially international ones) feel safe, respected and valuable if they want to compete or stay competitive in the international market.”

Liked this? Then you’ll love these…

What it’s like to be a Muslim student in Britain today – report

UK authorities on-hand after students receive ‘Punish a Muslim Day’ letters