Experimental theatre is a slice of privilege usually reserved for more well-to-do youth from wealthier countries.

But Mohamad Hassan al-Akraa, one of the lead acts in one such play this weekend, is a refugee in Malaysia, a country notorious for its treatment of asylum-seekers.

This will not be the first theatre production Hassan has participated in, though. Back in Aleppo, Syria, the lanky 17-year-old had acted in two plays in his high school … but that was before war struck his hometown more than six years ago. It was during, as he says, the days of his “perfect life”.

Hassan and the other teens rehearsing for FAME Festival’s We Are Human at a Kuala Lumpur studio this week look like any other group of kids.

Ahmad and Ruid, both 11, are the most mischievous while 18-year-old Omar tries to get them to listen to the director.

Yet, in one sentence, Hassan says something which instantly tells you this is no ordinary rehearsal.

“Sorry, I’m a little sensitive to gun sounds,” he says after a slight recoil when one of the crew tests some background sounds of gunshots. Very politely, he asks if the volume could be lowered, too.

From Aleppo to Kuala Lumpur

This is not a holiday for Mariam and her family in Malaysia.

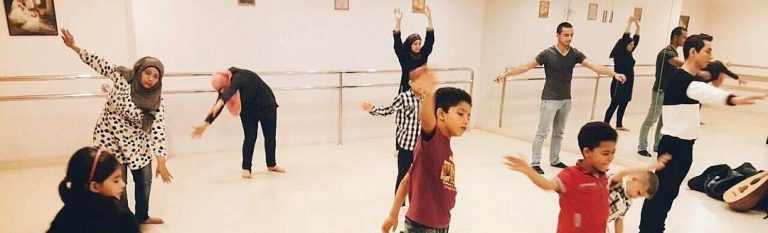

In the ballet studio leased from a music centre in Ampang, a suburb of the national capital, Hassan and eight refugee women and children, clad in black, glide about during a rehearsal for a play about their experiences as war migrants.

The youngest is nine-year-old Mariam, the Syrian-born daughter of Rawsha, an Iraqi refugee who fled to the country before the war.

In one scene, Mariam has to play catch with three sticks, each representing the country she has links with – Syria, her parents’ birthplace Iraq, and her country of refuge, Malaysia.

As the young girl struggles to catch each stick, all taller than her, her own strife for identity and citizenship is shown.

But identity will likely be the least of Mariam’s worries if she continues to live in Malaysia.

In a country which has not signed the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, the Malaysian authorities almost have carte blanche in their interpretation and implementation of local laws on these refugees.

Refugees like Mariam are typically treated more like illegal immigrants. They live in constant fear of deportation or arrest and detention.

Adults cannot work while children are barred from attending formal schools.

Though Syrian refugees have been informally deemed “first-class refugees” i.e. being accorded the most favourable treatment by the Malaysian authorities, they are not exempt from these fears and restrictions.

Three years ago, then 14-year-old Hassan was detained by the Malaysian Immigration Department for flouting a law which prohibits refugees from working.

He explained he was forced to work as his father was ill and could not support his family.

But his explanation fell on deaf ears and Hassan was forced to spend nine harrowing days in detention before being released with the help of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Malaysia.

Apart from living in fear of incarceration, refugee youths like Hassan are fleeced of another basic human right: education.

Though he dreams of getting a degree in education to become a teacher, a formal education is off the books for him.

This leaves Hassan, and others like him, to depend on hodgepodge, informal education from non-governmental organisations.

Against this backdrop, these daily rehearsals are the closest these youths will ever get to an education, especially one in the arts.

Although director Razif Hashim was pressed for time, he made sure his young cast members understand the basics of drama, such as theatre exercises.

“I teach them five things. First of all, you breathe. Then, you focus, you make eye contact, you say ‘Bismillah’ (in the name of God) and then you just to leave it to God,” he said.

Apart from having a creative outlet and learning drama, what Omar loves above all is how the cast is like family members, instead of treating one another as just actors or actresses.

Pointing to Hassan, he says, “I feel like this one is my brother. These are my new friends, my new family.”

Liked this? Then you’ll love these…

This new online resource will help get refugees into university

Lack of laws for education leaves refugees in Southeast Asia vulnerable, with no jobs