While opting for a reusable bag while grocery shopping can help reduce plastic waste, it does not ultimately solve the problem of overflowing plastic waste in landfills or oceans.

Besides, to make a cotton bag a truly environmentally friendly alternative to a conventional plastic bag, it has to be used at least 7,100 times, according to the Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark.

That’s a lot of grocery shopping trips.

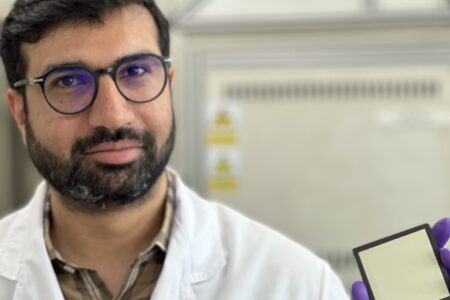

Feranmi Victor Olowookere, a PhD in Chemical Engineering candidate at the University of Alabama, is aware of the dangers of plastic pollution and is finding ways to reduce this waste by running molecular simulations.

The world produces between 350 and 450 million tonnes of plastic per year, and around 0.5% of it ends up in the ocean. In 2019, a study commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund and carried out by the University of Newcastle, Australia, found that we consume at least five grams of plastic weekly — equivalent to the weight of a credit card.

The world produces between 350 and 450 million tonnes of plastic per year, and around 0.5% of it ends up in the ocean. In 2019, a study commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund and carried out by the University of Newcastle, Australia, found that we consume at least five grams of plastic weekly — equivalent to the weight of a credit card.

“It’s a problem that the world is facing,” says Olowookere. “Recycling has been a way for many to reduce the amount of plastic, but it devalues the plastic material itself.”

In general, recycling includes compressing the waste, heating it, and moulding it into something else. Olowookere wants to take it to a different level — a molecular one, in fact.

“For PhD research, I’m looking for ways to turn certain molecules in plastic into something useful and valuable,” he says.

But before looking for ways to save the planet and humankind, Olowookere had other plans and getting to where he is today was far from a walk in a park.

Olowookere at Snowbird in Wasatch Mountain Range in Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah. Source: Feranmi Victor Olowookere

Chemical Engineering: A degree with the best prospects

Born and raised in Lagos, Nigeria, Olowookere is the youngest of four siblings. His father is a retired banker, while his mother is a teacher. Two of his older siblings became doctors, and another became an HR professional.

When it came time to decide what degree to pursue, he was at a crossroads between an architecture and an engineering degree.

The first offered little opportunity.

“Growing up in my household taught me to reach for more, but when it came to choosing my degree, I felt like because of traditions in Nigeria, I had to choose between a degree in engineering or medicine,” says Olowookere. “Architecture was out of the picture.”

Medicine, he knew, wasn’t going to be it either.

It was a field he wouldn’t have enjoyed, and besides, there were already two doctors in the family.

Engineering was the last option, and choosing which speciality was simple.

Olowookere opted for chemical engineering for its versatility and because earning this degree would open up the opportunity for him to work in the oil industry — something that Nigeria is known for.

In 2016, Nigeria had proven oil reserves of approximately 37.1 billion barrels, the largest in Africa. As of 2024, the country has exported US$52.1 billion worth of oil or 3.59% of the global total.

It’s no surprise, then, that demand for experts in this field is high.

After all, it was only 52 years ago, in 1973, when Nigeria’s first set of 14 locally trained students graduated from the University of Ife. Before that, most Nigerian chemical engineers in the mid-1950s had to pursue a degree from UK or US universities, and the profession was relatively unknown until the late 1960s when several trained graduates returned.

Today, Nigeria has over 35 universities and 12 polytechnics for chemical engineering.

With that decided, Olowookere joined a five-year-long BSc in Chemical Engineering programme at the University of Lagos in 2015. He graduated in 2022, two years later than planned.

Olowookere graduated with his MSc in Chemical Engineering from the University of Alabama. Source: Feranmi Victor Olowookere

This delay was primarily due to the strikes by the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU). The reason behind it? ASUU was demanding improved funding from the government for public universities.

During this time, as university lecturers weren’t teaching, students don’t attend classes. In Olowookere’s case, that went on for eight months in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It was extremely frustrating because we were supposed to finish our degree in just five years but it was extended indefinitely,” he says. “No one knew when they were going to graduate. It was also demotivating because I did not know where to go or do whenever it happened.”

Despite the discouragement, Olowookere’s good academic results kept him determined to see his degree through while his friends left school to find jobs.

However, he wasn’t just waiting around for classes to resume. During that period, Olowookere picked up a new skill: UX design. He got so good at it that he even spent eight months working as a product designer before graduating from university.

With his bachelor’s degree in hand, Olowookere wasted no time in packing up his belongings and heading straight to the US to pursue his master’s and PhD in Chemical Engineering.

It wasn’t a decision made on a whim, however.

It was in his third year of his bachelor’s when he decided to search for opportunities in the US. Compared to Nigeria, there’s no doubt that the US offers the space and academic standards to achieve goals that international students strive towards.

Take Stanley Peter Anukwuocha, for example. Moving to the US to complete his master’s degree was a stepping stone to starting Education African Scholars Global Connect, an organisation dedicated to helping African youths achieve their dreams of studying abroad. He was also awarded a prestigious national award from the National Forum for Black Public Administrators (NFBPA).

Anukwuoch wouldn’t have been able to achieve this if he had been back home in Nigeria.

Today, Olowookere is a PhD in Chemical Engineering candidate at the University of Alabama.

Olowookere pictured presenting his research poster as part of his degree. Source: Feranmi Victor Olowookere

Saving human civilisation through a PhD in Chemical Engineering

Chemical engineering is a branch of engineering that uses maths, physics, chemistry, and biology to design and operate processes that convert raw materials into products. In simple terms, it’s the process of producing, transforming, and transporting material.

This field of engineering also goes beyond just the lab, and that’s what Olowookere is most keen on.

“I don’t like being in the lab, and during my bachelor’s, I found that I like working with computational modelling,” he says. “So for my PhD, I decided to focus on molecular simulation of plastics.”

The goal? Saving the planet and human civilisation.

Plastic production and disposal account for 3.4% of all global greenhouse gas emissions, RMI reports.

Nearly one-quarter, 82 million tonnes, of the world’s plastic doesn’t end up not in landfills, recycled, or incinerated. Of that, at least 1.7 million tonnes find their way into the ocean, meaning at least 0.5% of the world’s plastic waste ends up in the sea, according to the OECD’s Global Plastic Outlook.

Mountains aren’t spared from this pollution too. 1Everest reports an estimate of 40 tonnes of garbage on Mount Everest, much of it buried in ice and snow due to increased human traffic.

This threatens the health and well-being of the local communities as the mountain’s glaciers provide for 65% of the domestic water supply in Khumbu Valley. The seas around it are now suspected to contain microplastics as well, which may cause locals digestive issues, toxic exposure, and other long-term effects.

“Even if we want to reduce the use of plastic, we can’t, as almost 95% of things we use in our life are made of plastic,” laments Olowookere. “It’s so commercialised since the 1950s that we can’t escape it.”

The life of a plastic item goes like this: once they’ve been used, they get tossed into landfills or the bottom of the ocean, where they don’t decompose for at least a thousand years. Even if they do decompose, they turn into microplastic.

“The fish will eat the microplastic, and we catch the fish to eat them, so we’re indirectly consuming it,” says Olowookere.

It’s the circle of life, but with plastics.

While recycling can be an option to reduce waste, it can be expensive, and the recycled material can only be used once or twice.

Olowookere is hoping that he can reduce plastic waste by taking a molecular-level approach to this problem. This is done through a computational simulation that zooms into the plastic and observes how the molecules behave.

With this, he can break down the plastic molecules and extract the carbon to be used for another product. The simulation will also help speed up the research process — something that could take six months to a year can be shortened into just a month or two.

For example, if his team wants to create a new solvent to dissolve plastic, Olowookere can simulate and develop models with thousands of chemicals. He can then streamline it to the most effective ones and hand the information to scientists to create in their labs.

He hopes that one day, through his research, there will come a time when oceans and landfills aren’t filled with plastics for the sake of future generations.

Oolowookere pictured on a hike at Lake Harris, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Source: Feranmi Victor Olowookere

A word of advice from someone who’s been there, done that

For Nigerian students looking to pursue a master’s or PhD in chemical engineering, Olowookere advises that it’s best to start looking for programmes as soon as possible — like in your first or second year.

“You should also learn how to write and get involved with research departments — get involved in leadership positions, mentorships, and anything related to that,” he says. “Studying from books isn’t everything; you should get hands-on experience.”

It is something Olowookere wishes he had gotten more involved in his undergraduate dates, so keep it in mind as you tackle your studies.