Did you know that food waste is a global crisis? According to the United Nations, nearly one-third of all food produced is estimated to go to waste, while 820 million people go hungry.

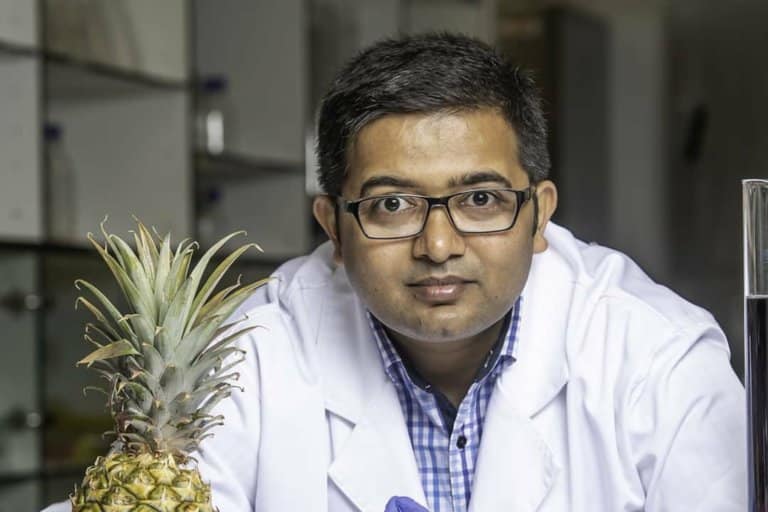

In Australia, one Indian scientist is on a mission to turn food waste into high-valued chemicals. Meet Dr Kiran Mahale, a Research Scientist and biotechnologist enthusiast from the University of Southern Queensland who is famously known for turning food waste into fuel — which started when he discovered leftover solid residues discarded from grapes.

“Winery waste has around 5% anthocyanin left in it, so I invested and developed new technologies to extract and purify those anthocyanins from winery waste,” he tells Study International. Once purified, Mahale explains that these chemicals can be sold at 850 Australian dollars for 10 milligrams.

Mahale explains that these chemicals can be sold at AUD $850 for 10 milligrams.

That’s not all. The researcher continued to synthesise this compound. Dr. Mahale further extracted the fermentable sugars after anthocyanin extraction utilising 100% of the winery waste.

He would further ferment (that refers to the metabolic process which produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes) that into ethanol, butanol, methanol or propanol. These alcohols can be blended with petrol to create a cheap and eco-friendly alternate reusable fuel option.

Early life in Maharashtra

Growing up, Mahale saw the realities of food waste. His father, being a farmer, taught him the importance of food. “In India, we worship food as a god,” he recalls. “My parents taught me that food was worshipable, so we cannot afford to waste it.”

At a blood bank, Mahale discovered how blood was separated into different components and used in various areas. That kickstarted his passion for biotechnology and prompted him to pursue a Bachelor of Science in Microbiology at North Maharashtra University.

Upon graduation, the Indian graduate secured a scholarship to complete a Master of Biotechnology (Honours) from Deakin University. While visa issues forced him to return home, Mahale’s meeting with a professor — speaking at a conference — saw him return to the Land Down Under to pursue his PhD in Renewable Energy at the University of Southern Queensland.

Mahale’s greatest work perhaps was working on extracting and purifying anthocyanins from winery waste and converting them into a cheap, eco-friendly alternate reusable fuel option. Source: Source: David Martinelli

Studying in Australia: A natural choice

The nature of Mahule’s work required a particular set of facilities — and Australia had that. Look no further than the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), an Australian government agency responsible for scientific research.

“They have the facilities that we haven’t seen anywhere in the southern hemisphere. The town Geelong, next to Melbourne, has the only lab which is capable of doing PSV for lab,” the Indian scientist explains. In these labs, scientists could deal with nasty viruses, and Deakin University’s campus was close to that facility.

His first project? Working with orange waste. That includes orange skins and pulp seeds. “I extracted a flavonoid called naringenin, which has a huge potential in the pharmaceutical industry,” says Mahale.

“It takes around 16 to 18 hours to extract and purify it. I developed a different method of extraction, which can be finished in three hours.” He did the same in his PhD with winery and pineapple waste.

Dealing with the language and cultural barrier

Since English was his third language, Mahale had to adapt to learning the language. Despite this, the Indian student developed sufficient competency in the language to pass his IELTS. A diverse international student community and English-speaking groups further polished his fluency in the language.

Before arriving in Australia, Mahale had never celebrated Christmas. He adds, “I did not know what a footie was. Here, they call footie football. But when I saw [them playing] football, there were playing with their hands and legs. I was like, ‘If you touch football with your hands, that’s a ball.”

If you’re considering a career in biotechnology, Mahale advises: “Develop a strong foundation in this area and ensure you clearly understand basic scientific concepts. After that, choose the area you want to specialise in, as biotechnology is vast. In the past, it was about agricultural science, but the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted the focus to health science.”