Back home, Chinese New Year was a time of reunion. Before the sun rose, I would be in my dad’s car — dozing off — as we made our way back to Sagil, a small settlement in the Tangkak District of Johor, before heading further down to the city of Kluang.

Every year, I would look forward to the food. Tilapia (“fei zhou you”), Hainanese Chicken, and Yam Cakes were some of my favourites. On top of that, nothing beats drinking classic soft drinks like Pop, Sprite, and 100 Plus after a delicious meal.

During this time, relatives would bombard us with a myriad of questions.

“How many more years till you graduate?”

“What are you studying now?”

“Did you grow taller?”

They were a hassle to answer. Looking back, however, I’ve grown to appreciate their interest in my life. After all, I was the first person to study law in my family.

That all changed when I moved to Belfast, Northern Ireland — over 10,000 kilometres away from home — to get a law degree.

Thanks to my spontaneous Malaysian friends, I always felt that I was part of a community even when studying abroad. Source: Nathan Hew

Finding my “family” away from home

Growing up, I wasn’t as close to my family compared to my friends. Unlike my brother, I am an introvert — so I liked being aline.

It wasn’t until I started to live abroad in Northern Ireland that I saw the true meaning of this quote:

“You never realise the value of something until it’s gone, hence why you should always appreciate the little things in life.”

I realised how much I missed the banter within my family or my twin brother talking with me.

Yes, homesickness hit hard — and the cold made it feel worse. You can imagine how tough it was to celebrate Chinese New Year in January when temperatures could get to an average low of three degrees Celcius.

Where I’m from, we have summer all year long and I doubt anyone feels celebratory when they’re freezing.

Good food, great conversations — that is how you celebrate Chinese New Year abroad. Source: Nathan Hew

Celebrating Chinese New Year in Northern Ireland

Lucky for me, Belfast has an incredibly tight-knit international student community.

Apart from those who transferred from Brickfields Asia College (a famous law school in Malaysia), I have met other Malaysians who have lived in Northern Ireland for a few years. Moreover, I was mingling with many of them for the first time in a foreign country.

With that, I had plenty of opportunities to create a reunion feast with my friends.

One famous spot was the Chili House, a popular place for many Asians to eat since they served authentic Chinese food. Nothing beats savouring a bowl of hot soup during winter.

Of course, Chinese New Year was also a time to receive our red envelopes, better known as “hong bao.”

As students, we couldn’t give out these envelopes. Some of my friends had a bold yet practical idea: they would pack chocolate coins in red envelopes.

Let’s not forget the Chinese New Year songs. Playing the regular tunes that I would listen to during this time of the year transported me to my parent’s hometown briefly.

Oddly enough, I was the only Malaysian to live with four flatmates from different parts of China — so that brought me back to my roots.

Surprisingly, my Chinese improved and I grew to appreciate my identity as a Malaysian Chinese. It was also interesting to see the different dishes they would whip in the kitchen during this festive period. For example, there’s a difference between the dumplings made in China and Malaysia.

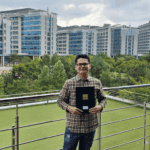

Celebrating Chinese New Year in 2022 with some of my friends who graduated from Queen’s University Belfast. Source: Nathan Hew

How Chinese New Year feels different when you graduate

The questions start to change.

“Where are you working?”

“Are you in a relationship?”

“Don’t you want to move to Ireland?”

Perhaps what surprised me was how I started to bond with my twin brother.

I genuinely started to enjoy his company — even more so when I saw him enthusiastically with my relatives during Chinese New Year.

As working adults, the New Year break is also a good time to rest and reset before we start a new cycle in the lunar calendar.

What stayed the same, though, was my family.

My parents are still naggy, but they tend to show their love in different ways, such as ensuring that we have a roof over our heads.

Alright, that’s the end of my story. I got to call my mum, dad, brother, and cousins to the dinner table.