As the world heats up to the point of no return, there’s still a stark gap between business and sustainability at many companies.

Living in Latin America, Rodrigo Berner Bensan felt it acutely. Structural issues like poverty, inequality, and climate change were prevalent and he saw the need for “innovative, socially focused solutions.”

“The emergence of social innovation strategies that aimed to address these problems and benefit society as a whole resonated strongly with me,” he says.

The industrial engineering graduate from Universidad de Chile saw value in helping businesses protect the environment.

To heed the call to make the world more sustainable, he felt he needed to leave his consulting role in Santiago for an unlikely country: Malaysia.

Smoke rises from forest fires at the Batu Caves hill in Kuala Lumpur on February 26, 2016. Source: AFP

Malaysia: Where business and sustainability do not merge

According to the Sustainable Development Report 2021, Malaysia ranked 65 out of 165 countries with an SDG Index of 70.9%.

“We succeeded in achieving one of the 17 goals, namely SDG1 (to end poverty in all its forms everywhere) and we are on track to achieve three other goals — affordable and clean energy (SDG7), decent work and economic growth (SDG8) and industry, innovation and infrastructure growth (SDG9),” says Noraida Saludin, president of Malaysian Institute of Planners.

That leaves 13 other SDGs that aren’t being met, including the following which are directly related to the environment:

- SDG13: Climate action — Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

- SDG14: Life below water — Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

- SDG15: Life on land — Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

Out of 477 monitored rivers, only 47% of the rivers were classified as clean, a Malaysian Environmental Quality Report 2016 found. The rest were slightly polluted (43%) and polluted (10%).

On land, there is estimated to be more than a million tonnes of post-consumer plastic waste.

From 2002 to 2022, Malaysia lost 2.85 Mha of humid primary forest, equivalent to four million football fields.

This came up to 33% of its total tree cover loss in the same time period, according to Global Forest Watch.

When humans raze or thin forests, it can drive many species into extinction. In 2019, Malaysia lost its only surviving Sumatran rhinoceros.

There are now less than 200 Malayan tigers, the only tiger subspecies inhabiting the Malay peninsula, left in the wild. Their numbers are rapidly declining.

These figures hardly paint Malaysia as a beacon of business and sustainability.

Why did Bensan head here?

While the mission to bridge business and sustainability is big, Bensan (pictured on the right with his wife), doesn’t forget to have fun. Source: Rodrigo Berner Bensan

Bridging the gap between business and sustainability: From industrial engineer to climate analyst

For over a decade, Bensan was a Boy Scout — a childhood that exposed him to the importance of conserving the natural world.

When he went to university, the engineering student saw the profound impact of sustainability and climate in the industrial sector when he worked on the Santiago Climate Exchange (SCX) for his thesis.

“The SCX was a relatively new player in the emerging carbon credit market in Chile,” he says.

“It focused on carbon neutrality certification, emission reduction projects and its role as a marketplace for certified projects resonated with my desire to make a positive impact on the world.”

It pushed him to pivot into becoming a climate analyst.

He adds: “I realised that I could contribute to both environmental conservation and corporate sustainability efforts, aligning perfectly with my values and goals.”

Unique challenges Chilean business and government faced in protecting the environment

Since graduating, Bensan has wasted no time in pursuing his passion.

He advised on the financing applications for a wide range of projects, including those in energy and forestry, where sustainability considerations were crucial.

By designing and implementing the country’s first Indigenous Development Programme, the Project Developer and Advisor at CORFO — Chilean’s economic development agency — allowed indigenous communities to access financing for projects with multicultural relevance.

“My involvement with The Eco Note, as its co-founder, provided a platform to promote sustainability and innovation in the business world,” he shares.

“This initiative helped raise awareness about corporate sustainability practices, including topics like the Corporate Sustainability Index and the Hydrogen Society, which are directly related to the challenges businesses face in Chile.”

Through his roles, Bensan had a clear view of the unique challenges Chile faced in bridging the gap between business and sustainability.

Businesses aren’t reducing their carbon footprint, transitioning to renewable energy sources, or investing in green technologies.

Bensan wanted to know how to get businesses to get serious about this. And Malaysia seemed like the perfect place to learn how to do it.

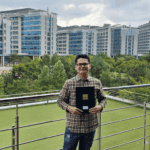

Bensan pursued his Master in Business Administration at the Asia School of Business (ASB) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Source: Rodrigo Berner Bensan

Moving to Malaysia to pursue an MBA

Bensan was attracted by the MBA at the Asia School of Business (ASB) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

“First and foremost, ASB’s unique partnership with MIT Sloan School of Management (MIT Sloan) was a significant draw,” he shares.

“This collaboration not only brought together the strengths of two esteemed institutions but also ensured that I would receive a world-class education.”

It complemented ASB’s approach towards learning, which was inspired by MIT Sloan’s motto of “mind and hand.”

Action Learning opportunities throughout Asia for MBA students at ASB include:

- one-week study treks to global financial hubs, companies, and institutions of interest

- one-month MIT Sloan Immersion

- the opportunity to earn an MIT Sloan Certificate of Completion.

“Beyond academics, the cultural diversity in Malaysia, encompassing various languages, ethnicities, and religions, was an intriguing aspect of living and studying in Kuala Lumpur,” he says.

“The rich culinary heritage, with a mix of Malaysian, Chinese, Indian, Thai, Korean and Japanese, among multiple cuisines, was an enticing bonus that spoke to my love for food and cultural exploration.”

Nothing beats a good meal after futsal. Source Rodrigo Berner Bensan

Through the ASB’s Sustainability Practicum, he worked closely with ASB’s Procter & Gamble Centre for Sustainable Small Owners (CSS) in Batu Pahat and Pontian districts of Johor, a state on the southern tip of Malaysia.

“I had the unique opportunity to dive deep into the complexities of the palm oil supply chain. Collaborating with my peers, we applied management and sustainability frameworks to collect and analySe data from farms, collection centres, and palm oil mills,” he shares.

It showed him the challenges and opportunities within the palm oil industry, a sector notorious for its environmental and social implications, and gave him a holistic perspective on sustainable supply chain practices.

With this knowledge, Bensan feels better prepared to champion sustainability initiatives within businesses, advocating for responsible sourcing and ethical practices.

“Moreover, it has sharpened my ability to identify areas where businesses can make a positive impact by implementing sustainable strategies and aligning them with their broader goals,” says the MBA graduate.

The divide between business and sustainability was shrinking.

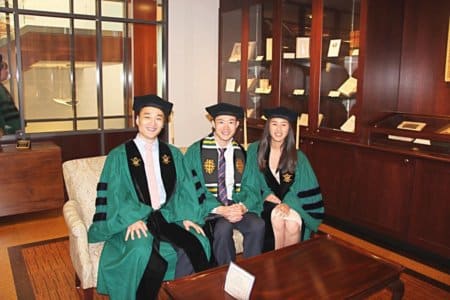

“This special arrangement not only expanded my academic horizons but also enriched my skill set, ultimately preparing me to make a meaningful impact in the fields of management, innovation, and sustainability,” Bensan shares about his time at MIT Sloan. Source: Rodrigo Berner Bensan/LinkedIn

Completing a Master of Science in Management Studies at MIT Sloan

A special bonus for those pursuing their MBA at ASB in Malaysia is a chance for graduates like Bensan to pursue a Master of Science in Management Studies (MSMS) at MIT Sloan.

In addition to being STEM-designated, this programme granted the ASB MBA graduate a chance to secure work authorisation in the US for three years upon completing the MSMS.

What’s more, this master’s programme had an elective-focused curriculum, allowing students to dive deep into an area of interest with courses offered solely at MIT Sloan.

“From my ASB cohort, four students, including myself, were fortunate to be accepted into the MSMS programme,” he shares.

“During my time at MIT Sloan, I had the privilege of conducting my thesis work under the guidance of Professor Robert Rigobon, a renowned expert in management, sustainability and applied economics.”

His thesis, titled “Matching Individual Environmental, Social, and Governance Revealed Preferences with Investment Portfolios,” provided valuable insights into the intersection of business and sustainability analytics.

At the same time, Bensan earned an MIT Sloan Business Analytics Certificate, which equipped him with essential competency in analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence — vital skills that are key to succeed in “contemporary organisations.”

The term is coined for companies that empower employees to make decisions and implement changes without needing the approval of supervisors.

Now, as he graduates from MIT Sloan, Bensan has found ways to close the business and sustainability gap.

“I envision myself actively promoting climate policies, advocating for the decarbonisation of operations and businesses in Chile, and championing the investment in green technologies,” he shares.

“I also believe that my entrepreneurial spirit will continue to drive me to explore innovative solutions and potentially venture into entrepreneurship, all with a strong focus on sustainability.”

Asia may not be the world’s most sustainable region, but analysts predict there is a US$5 trillion green business opportunity here that’s ripe to capitalise on. Source: AFP

Business and sustainability: What the future holds

Bensan has a long road ahead of him. Despite their critical role in addressing social and environmental challenges, most businesses still take a fragmented, reactive approach.

There are ad hoc initiatives to enhance their “green” credentials, comply with regulations, or deal with emergencies but most aren’t treating sustainability as an issue that directly impacts business results.

While a 2011 Harvard Business Review article predicted that sustainability would soon “simply be how business is done,” business and sustainability in 2023 just aren’t doing good enough.

For the past 20 years, businesses have increased reporting and sustainable investing, but carbon emissions have continued to rise, and environmental damage has accelerated.

According to a 2016 study that examined more than 40,000 CSR reports, less than 5% of reporting companies made any mention of the ecological limits constraining economic growth.

This is the reality Bensan has to contend with.

Asked about his end goal, Bensan shares: “My ultimate goal is to bridge the gap between business and environmental stewardship, creating a more sustainable and prosperous future for both.”