On February 27, 2026, the Grand Ballroom at Renaissance Hotel was abuzz, filled with people from all walks of life, but united by one common factor: They’ve all studied in the UK.

These people were here to network, yes, but also to witness and celebrate four Malaysians – all alumni of universities in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland – who were selected for the British Council’s Study UK Alumni Awards Malaysia 2026.

The awards, currently in its seventh edition in Malaysia, feature four award categories:

- Business and Innovation, honouring those driving economic growth through forward-thinking ideas and enterprises

- Culture, Creativity and Sport, a newly introduced category celebrating artistic and athletic excellence

- Science and Sustainability, recognising alumni championing solutions that protect our future

- Social Action, acknowledging individuals empowering communities and creating positive societal impact

Here are the four Malaysians that clinched the awards.

Dr Rebecca Tay Sook Hui receiving the award for Business and Innovation. Source: British Council Malaysia

1. Dr Rebecca Tay Sook Hui, winner of the Business and Innovation category

Graduate of: University of Nottingham, Universiti Putra Malaysia

Degree: Doctor of Philosophy, Pharmacy (Nottingham) and Molecular Medicine (UPM)

Graduated in 2021

One word to encapsulate Dr. Rebecca Tay Sook Hui, an alumna of the University of Nottingham, is inspiring. She’s someone who turns emotions into actions and boy has she gone through plenty of emotional experiences.

The CEO of Beacon Precision Diagnostics and Precision Diagnostics turned her grief from losing her mother at a young age into a zeal to bring pharmacogenomics to Malaysia.

Pharmacogenetics is the study of how an individual’s genetic makeup affects their response to drugs, merging pharmacology and genomics to enable personalised medicine. Having lost her mum to cancer, this is something that Dr Tan genuinely is dedicated to researching.

Her expertise in pharmacogenomics allowed her to tailor treatment for her stepmother when she was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in 2019. With this help, her stepmother pulled through, enjoying an excellent quality of life for over five years after diagnosis.

While often used interchangeably, pharmacogenetics typically refers to single gene effects on drug metabolism, whereas pharmacogenomics covers the influence of the entire genome.

The University of Nottingham alumna has also consulted on a national roadmap, believing deeply in the value of her work.

Thanks to her efforts, the Study UK Alumni Awards recognised her in the category of Business and Innovation.

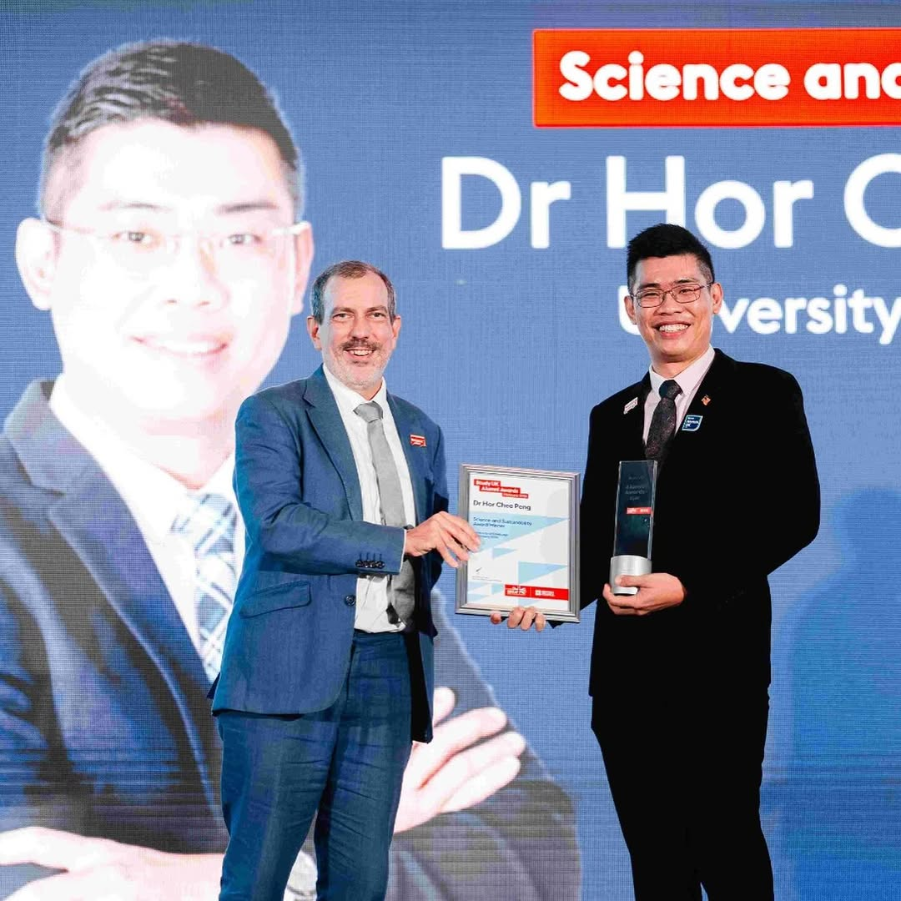

Dr Hor Chee Peng receiving the award for the Science and Sustainability category. Source: British Council Malaysia

2. Dr Hor Chee Peng, winner of the Science and Sustainability category

Graduate of: University of Edinburgh

Degree: Master of Science in Global Health and Infectious Diseases (Online Distance Learning)

Graduated in 2014

Dr Hor Chee Peng was recognised by the Study UK Alumni Awards for his impact in leading his hospital’s pandemic preparedness and response.

A proud Commonwealth Scholar, he attributes his ability to manage the evolving needs of the hospital during that period to the evidence-based approach, systems thinking and collaborative leadership learnt during his time in the UK.

He shares that his time at Edinburgh gave him the confidence to make rapid decisions without compromising scientific rigour.

While he trained as a doctor, studying public health in the UK fundamentally changed how he viewed healthcare. It taught him to think beyond individual patients and focus on systems and how they hold up under pressure.

Matthew Tan Yi Jian won the Study UK Alumni Awards for Culture, Creativity and Sport. Source: British Council Malaysia

3. Matthew Tan Yi Jian, winner of the Culture, Creativity and Sport category

Graduate of: University of Oxford; New York University

Degree: Master of Studies in Film Aesthetics; Bachelor of Fine Arts (double majoring in documentary filmmaking and philosophy)

Graduated in 2021 for his Bachelor’s and 2024 for his Master’s

Matthew Tan Yi Jian was recognised for his influential role in shaping the next generation of Malaysian storytellers.

His ethnographic documentary, “Partition” on Southeast Asian migrant women in the UAE was selected for the Oscar‑qualifying Short Shorts Film Festival and Asia 2024 and was nominated for Best Documentary Film at the British Film Institute’s (BFI) Future Film Festival 2025.

Passionate about nurturing emerging filmmakers, the judges were impressed by Tan’s commitment to amplifying Malaysian achievements in film on the global stage. He shared that he is passionate about shaping how film is made, taught, and understood through philosophy driven storytelling.

Studying film aesthetics at Oxford taught him how cinema can think, not just show. It gave him the language to connect philosophy and filmmaking, and to situate Malaysian stories within global conversations.

In particular, his time in the UK allowed him to gain access to one of the richest traditions of film scholarship in the world and gave him the opportunity to get immersed in a living film culture that extended far beyond the classroom.

On his return home, he brought that way of thinking into the classroom and work — mentoring students, shaping critical film culture, and creating films that foreground Southeast Asian voices on international stages. A Chevening scholar, Tan is currently an adjunct lecturer at Multimedia University.

Tan Shi Min was the winner of the Social Action category at the Study UK Alumni Awards. Source: British Council Malaysia

4. Tan Shi Min, winner of the Social Action category

Graduate of: University College London; University of St Mark and St John, Plymouth (Plymouth Marjon University)

Degree: MA Music Education; Bachelor of Education in TESL

Graduated in 2014 for her Bachelor’s and 2024 for her Master’s

The University College London (UCL) graduate has impacted the community in a demonstrable way with her innovative product, the Wheel of Learning, a multicoloured, multi-layered graphic organiser, which helped to increase English passing rate.

It has supported over 1,000 teachers and students and growing the English aptitude of her students in rural Malaysia.

Prior to UCL, the Study UK Alumni Awards winner was also a student at Plymouth Marjon University in England. She had received a full scholarship from the Ministry of Education to pursue her bachelor’s degree here.

Hailing from Penang, she now runs an initiative called “Projek Anak Malaysia” that has benefited over 5,000 students over the past 13 years. Her social work efforts were inspired by her time serving as an English teacher in a rural school where many students struggled with literacy.

British Council Malaysia Director, Jazreel Goh, delivering her welcome address during the Study UK Alumni Awards 2026 Malaysia ceremony in Kuala Lumpur. Source: British Council Malaysia

Beating 1,000+ other applicants

At the event, British Council Malaysia announced that it received over a thousand submissions, which went through rounds of longlisting and shortlisting.

This goes to show the breadth of talent and ambition among alumni in Malaysia, reinforcing the value of a UK education in equipping graduates with skills, perspectives, and leadership needed to succeed in a rapidly evolving global landscape.