A disgrace to the family — that\’s what Sarah fears becoming. “We say that if you drop out, you bring disgrace to the family,” she said. “It shows you don’t have enough perseverance to continue on, so it’s quite shameful.”

Sarah is one of many international students desperate to return to China. The PhD candidate has been locked out of the country since the first wave of the pandemic, when borders were abruptly shut to curb the coronavirus outbreak. What she expected to be a temporary disruption that would only last a month dragged to months. She did not predict she would be going up against what would be some of the world’s most formidable barriers to entry for foreigners. Or that she would still be waiting to return to her Chinese university almost two years later.

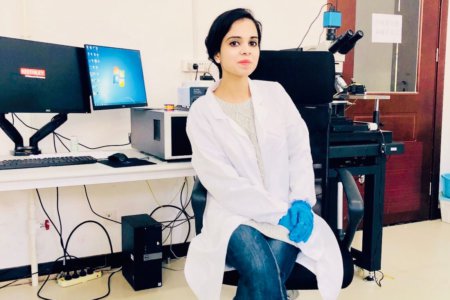

Since then, Sarah has been living in her family home in Singapore. This means juggling extra tasks, or what sociologists call the “double burden” of work and family responsibility. “A lot of times, when I’m doing my research, I still have to help out with the housework,” Sarah explained.

To balance her chores, research and teaching, she often has to work seven days a week. Her younger brother, who had dropped out of polytechnics and has more time to spare, is not expected to bear this burden. He is allowed to be “lazy” — a privilege she, as a daughter, is not afforded.

This gruelling predicament penalises Asian women. In 2018, women in Asia and the Pacific were found to spend 4.1 times more hours in unpaid care work than men. The pandemic exacerbated this, seeing a dramatic increase in the care work undertaken by women throughout the COVID-19 crisis.

The human costs of China’s “zero COVID” policy cut deeper still.

Grace and her husband decided to move from their home country, Senegal, to China in pursuit of a PhD, believing it would open professional doors for both of them. When their daughter fell sick, however, it was Grace who had to return home to care for her — and when China shut its borders to the world, it was Grace who suffered the consequences.

She had suspended her work contract for four years to complete her PhD. Now, shut out of her Chinese university for two years, her career will be in limbo for longer. “I lost years of my life waiting to go back because I can’t work with my supervisor online,” Grace said.

The prolonged uncertainty is beginning to take its toll. Grace fell into a deep depression, cutting her hair out of despair. Her family, however, doesn’t emphatise — they believe women shouldn’t be concerned about completing PhDs. Meanwhile, her husband is in China and on track to finish his PhD this year.

Indian parents can be just as dismissive of this loss in learning. “Most parents just want to show that their daughters have completed an undergraduate degree, but don\’t expect these women to use them,” explained Priya, a female medical student from India. “They don\’t allow their daughters to practise further.”

Sarah, Grace and Priya declined to be named for fear of professional retribution.

The stories by these women are not anomalies. They echo the new, disorienting reality of many international students who are locked out of China. As many as half a million have become collateral damage due to China’s uncompromising “zero COVID” policy, a hardline strategy to eliminate the virus by all means. The country’s international borders have remained shut to foreigners since March 2020.

For students stranded offshore, the policy has been nothing short of a complete upheaval to their lives and plans for the future. Trapped in academic limbo, many have taken to social media with hashtags such as #TakeUsBacktoChina and #TakeUsBackToSchool to voice their plight.

“We tried so many ways to make the universities hear our pleas, but they always replied the same thing, ‘Amendments will be made in the next semester,’” Priya laments. “That ‘next semester’ never came.”

Women in particular face unique challenges in higher education as a result of restricted global mobility. Frustrated, anxious, and desperate, female students locked out of China are weary from straddling expected care work and the additional pressures to succeed as a woman, according to questionnaires and interviews compiled by Study International.

Pitted against diminishing educational and career trajectories, some are taking the first exit they see by transferring to universities elsewhere. Others are not so fortunate and must ride out the border reopening waiting game — or risk losing everything they’ve sacrificed up to this point.

“My heart goes out to the international higher education students who have been locked out of China and have had their lives upended due to travel restrictions,” said Curtis S. Chin, former US Ambassador to the Asian Development Bank; and inaugural Asia Fellow of the Milken Institute, a nonpartisan, nonprofit economic and policy think tank.

\”Women and girls\’ education is critical to any nation\’s development needs,” he remarked in an email interview with Study International. “The impact of Chinese closed borders will be particularly felt in those nations that had hoped that Chinese universities would be a key provider of access to higher education for female students.”

This picture taken on Feb. 14, 2020 shows two men wearing face masks walking through a nearly empty terminal at Daxing international airport in Beijing, as travel has ground to a halt in the wake of the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak.According to the 2018 World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report, six out of 25 developing Asian countries had achieved gender parity in education. The numbers show even greater promise in tertiary education: 12 out of 18 countries studied have women outnumbering men in terms of enrolment rates.

This picture taken on Feb. 14, 2020 shows two men wearing face masks walking through a nearly empty terminal at Daxing international airport in Beijing, as travel has ground to a halt in the wake of the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak.According to the 2018 World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report, six out of 25 developing Asian countries had achieved gender parity in education. The numbers show even greater promise in tertiary education: 12 out of 18 countries studied have women outnumbering men in terms of enrolment rates.

In that same year, China admitted a record 492,185 overseas students to expand the ongoing internationalisation of its higher education sector. The country now hosts the largest cohort of foreign students in Asia — thanks in part to its generous volume of scholarships and good value-for-money education, which is far cheaper than studying in Western institutions.

These are major pull factors for students from South Asia and West Africa to obtain a Chinese education. “China offers a high number of scholarships, and many of these go to students who are poor and could not attend university otherwise – in their home countries or elsewhere,” said Heidi Østbø Haugen, Professor of China Studies at Oslo University.

“Because Chinese higher educational aid is so effective at reaching groups in need, a border closure is very dramatic. It takes away the only hope they had of getting a university degree,” added Dr. Haugen, who has done extensive research on migration in China.

“For several of the women in my study, China was also attractive because it was considered safe, and because China gives scholarships to women and men on equal terms. The border closure has removed an accessible university opportunity. This is a setback for young people who don’t have other options,” she added.

Greater educational access and mobility do not necessarily translate into career mileage and equal participation in the workforce for women in the Asia Pacific region. The pandemic reduced women’s employment in Asia and the Pacific by 3.8% compared to 2.9% for men, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

For women pursuing STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) careers in the region, the scales were already tipped against them before the pandemic. UNESCO Bangkok’s groundbreaking 2015 report, “A Complex Formula. Girls and Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics in Asia”, found that only three of 18 countries in Asia had an equal or above proportion of women participating in STEM-related fields.

The report also found that women in STEM are often concentrated in lower levels of employment with less job stability. At the higher levels, their representation decreases dramatically, whether in education or the workplace. An updated report in 2020 found that women eventually leave the field in disproportionate numbers, either during their education, their transition to the workforce, or during their career cycles.

This grim prospect is closing in on Nanditha, who is studying to become a doctor at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. She has missed all her lab work so far, a fate shared by medical students who are in a similar bind due to border closures.

“Honestly, my practical knowledge is still stuck in second year even though I’m already in my fourth year. The fear that I might not be a good doctor scares me every day,” says the Indian student. If the situation persists, Nanditha might not even become one. Without on-site practical training, her qualifications won’t be recognised for professional medical practice, leaving years of hard work in tatters. “It’s making me go insane.”