Martina Dimoska is not your “typical” international student. In a country where space exploration is unheard of, the Macedonian found her passion in engineering — to take off to the sky, literally.

“I grew up with a sister who had disabilities,” Dimoska explains. “Through my analytical thinking, I learned how to make her life more interesting, amusing, and helpful. That inspired me to solve bigger problems in my education and career.”

But breaking into the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) field was no easy feat. Data from the UN Scientific Education and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) shows that there are few women in STEM. Only 30% of female students select STEM-related fields at university.

To stand out, Dimoska was willing to put in the work. Even as a high school student in Kičevo, she participated in competitions and hackathons. As a postgraduate student, the Macedonian secured a scholarship to pursue a Master of Space Studies at the International Space University.

Recently, she became the first Balkan female analogue astronaut (a person who plays the role of an astronaut during a simulated crewed mission) to work with UND ILMAH – University of North Dakota Integrated Lunar Martian Analogue Habitat, which is supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

We caught up with her to learn more about her extraordinary journey:

Martina Dimoska participated in a simulated crew mission with two students at the University of North Dakota for 21 days. Source: UND ILMAH Crew 14 team

Tell us your background as an international student.

While I was admitted to various prestigious high schools, I couldn’t afford to study in the Capital. I studied at a high school in my hometown called Kicevo.

I went to do a Bachelor of Material Engineering and Nanotechnology at the Faculty of Technology and Metallury, UKIM – Skojpe in Macedonia because they were offering scholarships. Because of my GPA, I secured a scholarship that enabled me to pursue my studies.

When I was studying, I went to exchange studies in Germany and Europe. I have also been awarded a Global UGRAD grant, where I spent some time at Kent State on their aerospace campus in Ohio.

Once I saved enough to pursue my graduate studies, I knew I wanted to do it abroad. Fortunately for me, because of my involvement with the start-up sector, I was awarded the Aldrin Family Foundation Scholarship to study the Commercial Space Studies programme at the Florida Institute of Technology.

Likewise, I secured another scholarship to do my Master of Space Studies at the International Space University.

What are analogue astronaut missions?

They are common in the space sector. Analogue astronaut missions mimic various space scenarios. You could be on the moon or in an environment that mirrors another planet.

These missions are vital to the scientific community in space exploration. As we send more people into space — whether commercial or not — more testing is required to analyse the effects of space travel on the human body, covering issues like confinement isolation, blood clots, stress levels, and many more.

There is other research too. You test the habitat (a place where humans can get food, water, and shelter), supply, machinery, and all the systems. You can conduct experiments on the ground to see what works and can be improved before you go into space.

For example, suppose you have something flown on the International Space Station and have the same partner collaborating with you on the ground. In that case, you can compare the data, determine the flaws, or analyse if it behaves differently in space than on earth.

These experiments help to promote space exploration as only approximately 570 individuals have travelled into space.

These space suits help analogue astronauts like Dimoska to get a feel of conducting experiments in space. Source: UND ILMAH Crew 14 team

Could you tell us about the mission you were on?

There are different types of analogue astronaut missions — some private and some affiliated with a government, university, or specific organization. Our UND ILMAH 14 was organized by the University of North Dakota and the amazing Aerospace Department, aided by NASA.

We participated in a 21-day “Martian” scenario (The “Martian” refers to humans who practice life similar to a future Mars base). I served as the science officer, together with a flight engineer and a commander.

Within the confined area, we had a core module, a workout module, a geology module,a plant module, and an EVA (Extravehicular Activity) module.

Apart from wearing space suits, how do you simulate the sensation of being in space on Earth?

You can’t play with gravity, but you can control other factors. Missions can be conducted underwater, in the desert or in extremely cold places like Antarctica. There’s also the aspect of isolation, never leaving the habitat, and implementing a proper chain of command.

Sadly, you can’t isolate noises. Fortunately, people at the University of North Dakota have plans to perfect the simulation and separate analogue astronauts from the external environment to enhance the experience, and I am so excited about the high-fidelity missions they are planning to implement in the future!

Share with us some challenges you had to overcome as an international student eager to venture into the space exploration industry.

First and foremost, you need funding. Space exploration is a prestigious industry. When you think about graduate schools doing this type of research — the kind that is validated by the space community — countries like the UK, the US, or France come to mind.

The competition is fierce. In the US, high schoolers can enter NASA. You are fighting against people who could join the space agency much earlier or have done outstanding research over the summer. If you lack the experience, internship, right background or go-getter attitude, you’re starting on the back foot.

My country is also not a member of the European Union. Students like us need help to get funding as those from a member country with the European Space Agency has more opportunities to participate in projects that are well funded. They might even get a job afterwards. Without scholarships, it would be difficult for us to enter the industry.

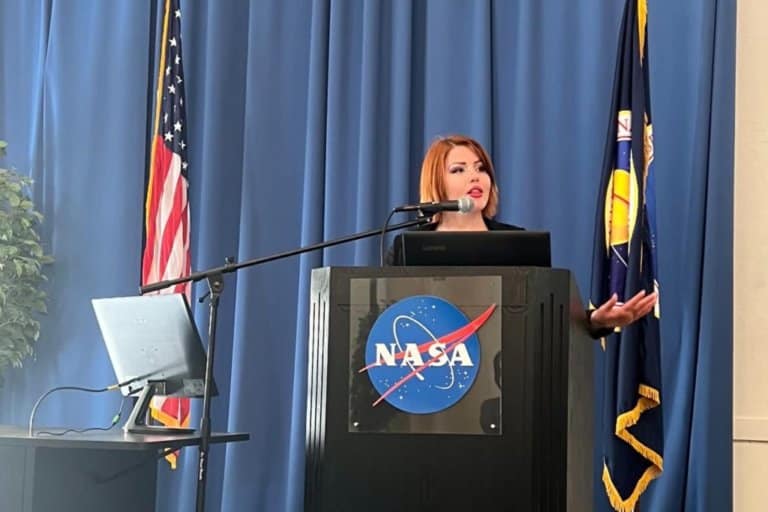

Dimoska (pictured in the centre) led the NASA Space Apps Challenge Mountain View, held at NASA Ames Research Center. Source: NASA Space Apps Challenge Mountain View at NASA Ames Research Centre

What were some of the cultural differences that you have experienced in the US?

I picked up a lot of languages before learning English. My first language is Macedonian. Coming from Macedonia, I have different traditions, values, and ways of life. Adapting to the modern, westernized civilization is challenging because my values can exclude me from participating in certain things. But I am never quick to judge and I am even quicker to adapt!

We did have cultural classes where our professors taught us that not everybody perceives the world the same. Sometimes you have to look back, rephrase and ask, “Is that what you meant?”

I am missing out on many social cues because of work overload. But I know that welcoming, well-cultured, and well-mannered people will fill me in and bring me to a proper level of understanding without hesitation.

Do you have any advice for students who want to kickstart a career in aerospace engineering?

You have to work hard to solve complex problems. Be prepared for sleepless nights and challenging days where you have to do a lot of work. If that’s your passion, build your knowledge.

I also actively post opportunities for people to participate in hackathons, host informative Zoom calls, and lead panel discussions on my social media platform like Linkedin. You can always find out more on my Instagram. The goal is to make everyone feel included and build an extremely proactive and kind community that tolerates all sorts of differences.

Practise a growth mindset. Once you are comfortable learning from your mistakes, that will help you thrive in one of the harshest industries.