The United Nations General Assembly has proclaimed 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages. In doing this, it says, it wants to acknowledge that

Languages play a crucial role in the daily lives of people…

Indigenous languages tend to be spoken by politically marginalised groups whose nations were historically colonised and their languages sidelined in favour of the colonisers’.

There are over 7,000 known living languages; about one third of them are in Africa. Most African children grow up in multilingual environments, and are often familiar with more than one language before they enter school.

The UN’s call makes it an opportune time to examine how best these languages ought to be re-empowered through intellectualisation and regular use in education. Drawn from my own extensive, decades-long research – and the work that’s been done by others in the fields of multilingualism and language education – I have drawn up a list of five ways that promise to work when it comes to meeting these goals. And I’ve explained why these approaches matter in the long term.

Doing this is a valuable way to develop, build and champion these languages. Simply continuing the status quo in education with the almost exclusive use of languages like English, French, Portuguese and Arabic will exclusively serve the interests of the former imperialist powers and perpetuates post-colonial political and cultural dominance.

Golden rules

Recognise and accept multilingualism as the norm: Many development models from the “Western” world imposed on African countries tend to be based on the idea that nation-states are ethnically and culturally homogeneous and basically monolingual. They are totally inadequate in the face of the essential linguistic plurality and diversity that is characteristic of the countries in the Global South, including those in Africa.

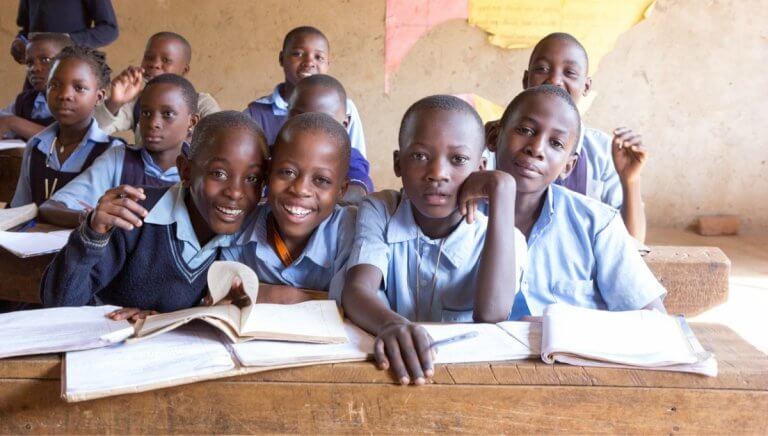

Don’t teach children in a language they do not understand: Globally, 40 percent of children don’t have access to education in a language they understand. There is no solid data for Africa, but the rate is likely to be much higher.

That’s because most African countries prioritise a language for education which is not a language that the children speak at home nor understand at the point when they enter school. They do this for several reasons. One is that the education system was already established at independence and people did not want to change something they perceived as working. Another is that most countries on the continent are home to several indigenous languages and new governments did not want to cause conflicts by prioritising one over another.

Globally, 40 percent of children don’t have access to education in a language they understand. Source: Dan Gold/Unsplash

This has serious consequences. For one, learning in a foreign language has a negative impact on test scores in practically all content subjects. Research has repeatedly shown that children who learn in their own languages, or mother tongues, are more involved in class and are more likely to complete their schooling.

Learning in the mother tongue also facilitates children’s ability to learn another language. This could be English or another “global” language, opening doors to learning or living in other countries.

If necessary, make education trilingual: Some countries may need to introduce a third language in their education systems. This is because of migration, displacement and the wide variety of languages found across Africa.

In this setup, schools would teach through the local mother tongue as a first language; a regional lingua franca or a national language as a second language, and a foreign or global language (English, Portuguese, French) as the third. This will secure early school success (through use of the first language). It will allow learners to acquire a relevant second language so they can participate and function fully in regional and national business. And it will equip them with a “world language” for official national and international business and politics.

This approach will minimise language barriers, as well as giving learners a competitive advantage when they leave school.

Trilingual education is being discussed widely on a global scale, but is being hesitantly implemented. The late Cameroonian linguist Maurice Tadadjeu proposed this approach for his country as early as 1975; Kazakhstan is working towards a trilingual education system with Kazakh, Russian and English. And Luxembourg is a success story: there, the majority of people are trilingual. Any number of African countries, among them Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Africa, could follow suit.

Make language policy inclusive: Mother-tongue based education fosters inclusion and equity. It has been shown to have positive effects on girls’ enrolment, attendance, achievements and transition from school to university rates. It also de-marginalises minority sections of the population, and can help to integrate migrants.

It will cost money now, but the long-term gains are enormous: Some argue that it costs a great deal of money to set up a multilingual education system. It does, but not that much: research has found that taking this approach may amount to only up to 2 percent of a country’s national education budget. And the rewards, as I’ve highlighted, far outstrip the investment.

What next?

The International Year of Indigenous Languages serves as a good impetus to start implementing policies that will prioritise Africa’s own languages on the continent. All the evidence suggests this could kick start a genuine “African renaissance”.![]()

By H. Ekkehard Wolff, Emeritus Professor of African Linguistics, University of Leipzig. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Liked this? Then you’ll love…

Should students use Netflix to learn language?

These are the top languages UK employers are currently seeking