Few people doubt the value of developing students’ thinking skills. A 2013 survey in the United States found 93 percent of employers believe a candidate’s “demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important [the emphasis is in the original] than [their] undergraduate major”.

A focus on critical thinking is also common in education. In the Australian curriculum, critical and creative thinking are known as “general capabilities”; the US has a similar focus through their “common core”.

Critical thinking is being taught successfully in a number of programmes in Australian schools and universities and around the world. And various studies show these programs improve students’ thinking ability and even their standardised test scores.

But what is critical thinking and how can we teach it?

What we mean by critical thinking

There are many definitions of critical thinking that are vague or ill-formed. To help address this, let’s start by saying what critical thinking is not.

First, critical thinking is not just being smart. Being able to recognise a problem and find the solution are characteristics we associate with intelligence. But they are by themselves not critical thinking.

Intelligence, at least as measured by IQ tests, is not set in stone. But it does not seem to be strongly affected by education (all other things being equal), requiring years of study to make any significant difference, if at all. The ability to think critically, however, can improve significantly with much shorter interventions, as I will show.

Second, critical thinking is not just difficult thinking. Some thinking we see as hard, such as performing a complex chemical analysis, could be done by computers. Critical thinking is more about the quality of thinking than the difficulty of a problem.

So, how do we understand what good quality thinking is?

Critical thinkers have the ability to evaluate their own thinking using standards of good reasoning. These include what we collectively call the values of inquiry such as precision, clarity, depth and breadth of treatment, coherence, significance and relevance.

I might claim the temperature of the planet is increasing, or that the rate of deforestation in the Amazon is greater than it was last year. While these statements are accurate, they lack precision: we would also like to know by how much they are increasing to make the statement more meaningful.

Or I might wonder if the biodiversity of Tasmania’s old growth forests would be affected by logging. Someone might reply if we did not log these forests, jobs and livelihoods would be at risk. A good critical thinker will point out while this is a significant issue, it is not relevant to the question.

Critical thinkers also examine the structure of arguments to evaluate the strength of claims. This is not just about deciding whether a claim is true or not, but also whether a conclusion can be logically supported by the available data through an understanding of how arguments work.

Critical thinkers make the quality of their thinking an object of study. They are sensitive to the values of inquiry and the quality of inferences drawn from given information.

They are also meta-cognitive – meaning they’re aware of their thought processes (or some of them) such as understanding how and why they arrive at particular conclusions – and have the tools and ability to evaluate and improve their own thinking.

How we can teach it

Many approaches to developing critical thinking are based on Philosophy for Children, a programme that involves teaching the methodology of argument and focuses on thinking skills. Other approaches provide this focus outside of a philosophical context.

Teachers at one Brisbane school, who have extensive training in critical thinking pedagogies, developed a task that asked students to determine Australia’s greatest sportsperson.

Students needed to construct their own criteria for greatness. To do so, they had to analyse the Australian sporting context, create possible evaluative standards, explain and justify why some standards would be more acceptable than others and apply these to their candidates.

They then needed to argue their case with their peers to develop criteria that were robust, defensible, widely applicable and produced a choice that captured significant and relevant aspects of Australian sport.

Learning experiences and assessment items that facilitate critical thinking skills include those in which students can:

- challenge assumptions

- frame problems collectively

- question creatively

- construct, analyse and evaluate arguments

- discerningly apply values of inquiry

- engage in a wide variety of cognitive skills, including analysing, explaining, justifying and evaluating (which creates possibilities for argument construction and evaluation and for applying the values of inquiry)

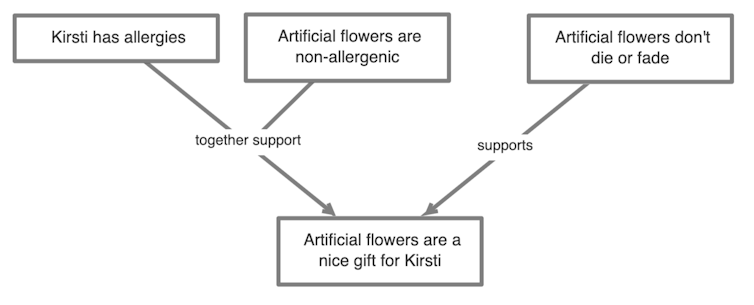

One strategy that also has a large impact on students’ ability to analyse and evaluate arguments is argument mapping, in which a student’s reasoning can be visually displayed by capturing the inferential pathway from premises to conclusion. Argument maps are an important tool in making our reasoning available for analysis and evaluation.

This map shows part of an argument in favour of giving artificial flowers over real ones.

How we know it works

Studies involving a Philosophy for Children approach show children experience cognitive gains, as measured by improved academic outcomes, for several years after having weekly classes for a year compared to their peers.

This type of argument-based intellectual engagement, however, can show high outcomes in terms of the quality of thinking in any classroom.

Research also shows deliberate attention to the practice of reasoning in the context of our everyday lives can be significantly improved through targeted teaching.

Researchers looking at the gains made in a single semester of teaching critical thinking with argument maps said: “the critical thinking gains measured […] are close to that which could be expected to result from three years of undergraduate education”.

Students who are explicitly taught to think well also do better on subject-based exams and standardised tests than those who do not.

Our yet-to-be-published study, using verified data, showed students in years three to nine who engaged in a series of 12 one-hour teacher-facilitated online lessons in critical thinking, showed a significant increase in relative gains in NAPLAN test results – as measured against a control group and after controlling for other variables.

In terms of developing 21st-century skills, which includes setting up students for lifelong learning, teaching critical thinking should be core business.

The University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project has a number of tools to help teach critical thinking skills. One is a web-based mapping system, now in use in a number of schools and universities, to help increase the critical thinking abilities of students.

By Peter Ellerton, Lecturer in Critical Thinking; Curriculum Director, UQ Critical Thinking Project, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Liked this? Then you’ll love…

Are critical thinking skills taught the ‘right way’ in schools?

Can we bridge the critical thinking skills gap with online learning?