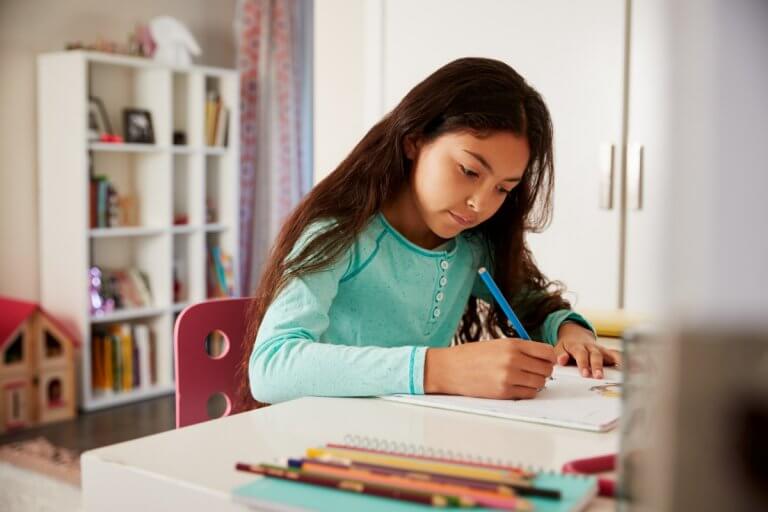

Most students in school – whether public, private, or international – can relate to the feeling of looking forward to a lovely break only to have a mountain of homework to complete.

The more diligent will complete it during the first few days so they can enjoy the holiday, but there are several who will wait til the last minute!

But should there really be homework during a school holiday? One teacher known as Sarah recently wrote on BoredTeachers how she believes that it is a mistake to assign homework over the break, even though she used to do it herself.

She wrote, “It’s taken a lot of experience and personal reflection, but after seventeen years of teaching high school students, I am firmly in the “not to assign” camp.”

She said that there was a time when she felt differently, especially when she couldn’t finish teaching a particular unit before a major break or felt like she wasn’t challenging her students enough, so she would assign some short papers or reading over the holidays.

“This was especially true when I personally wasn’t doing anything special over the break except staying at home. I guess I selfishly reasoned that if I was going to be spending part of my time off grading the work that I had already assigned, then they could be spending part of that time off doing homework for me.”

Are students spending the bulk of their school holidays finishing homework? Source: Shutterstock

But what Sarah realised is that she wasn’t the only teacher assigning homework, or who felt pressed to finish teaching what they’re supposed to before the break, which leads the homework to pile up for the kids.

“I was trying to do “all the things”, and assigning work over short breaks allowed me to fit more learning into each semester. Instead of focusing on increasing the quality of what I was assigning, I became more concerned about the quantity, convincing myself that the more I assigned, the better a teacher I became.”

Is homework just busy work?

When Sarah went on to become a Graduate Teaching Assistant at university while studying for her Master’s, she found herself on the other side of the desk and began to realise what was really expected of college students.

“All of my years of telling my students “in college you will need to be able to do this” felt like a lie. Yes, there were skills that I expected from my students that they did need to master to be successful in college.”

“However, skills were more important than me imparting all of the knowledge that I could and having them read everything that was humanly possible, in a single school year. In the end, cutting out a novel or short story was not going to break them, something I slowly realized as I made my return to the high school classroom.”

Both kids and teachers should be allowed to enjoy their breaks and use it as a time to relax and recharge. Source: Shutterstock

Becoming a mother also altered her views on children and the pressures they face in school. She wrote, “Parenthood changed the way I viewed my students. I no longer saw them as just students. They were sons and daughters with parents who were watching their babies grow into adulthood.”

Reality really hit home when her daughter started bringing home homework from kindergarten which seemed more like busy work rather than encouraging real learning.

“When she could have been playing or we could have been reading together for fun, she had to do homework for which I saw no academic value. More than before, I started to critically consider the homework that I assigned and reconsider the value and importance of each assignment.”

“These are the questions I have started to ask myself through every unit: Is this worth my students’ time? Is grading that assignment worth my time as well? What is the ultimate benefit of a given assignment and does the benefit outweigh the cost to both teacher and student?”

Sarah urged other teachers to realise that they are allowed to take well-deserved breaks, and in turn, allow students to enjoy those same, well-deserved breaks.

“We have to ask ourselves how much of a difference that extra work is going to make in the end. I know that some of my fellow educators, especially those teaching high stakes courses in a single semester, will struggle to cut back, and that is understandable.”

“But maybe the rest of us can take a moment to invite our students to enjoy the quiet, teaching them to practice the self-care that so many of us struggle with so that they can return to us after a break renewed and refreshed with hearts and minds open for learning.”

Homework can be good, but not too much

This week’s homework for parents is making an Easter bonnet and a garden shoe box. What homework has your school set you? pic.twitter.com/Qw1NJcuvGj

— Becky Allen (@profbeckyallen) April 1, 2019

However, in a study done by Duke University, researchers found that homework does actually have a positive effect on student achievement, especially for younger children.

Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and director of Duke’s Program in Education, said, “With only rare exception, the relationship between the amount of homework students do and their achievement outcomes was found to be positive and statistically significant.”

But it is noteworthy to mention that despite the findings, the analysis also showed that too much homework can be counter-productive.

He said, “Even for high school students, overloading them with homework is not associated with higher grades.”

“Kids burn out. The bottom line really is all kids should be doing homework, but the amount and type should vary according to their developmental level and home circumstances.

“Homework for young students should be short, lead to success without much struggle, occasionally involve parents and, when possible, use out-of-school activities that kids enjoy, such as their sports teams or high-interest reading.”

Therefore, assigning homework over breaks is not necessarily a bad thing. But teachers should re-evaluate if students are really learning through them, or they would be better off enjoying a rejuvenating holiday with some light reading or a fun project instead of hours spent poring over difficult homework.

Liked this? Then you’ll love…

What’s the point of taking AS-levels anymore?

How do you encourage innovation in schools? Listen to teachers and empower them