Recent announcements by the B.C. and Ontario governments emphasise that institutions of higher education should plan a familiar return to normal in campuses over the next month. Their recommendations call for a return to normal with an eye on backup plans and transitions.

But the research my colleagues and I have done suggests that faculty and students hope for better futures. They don’t want “a return to normal.”

Over the last year and a half, my colleagues and I have interviewed faculty across Canada and sifted through surveys gathering the opinions of nearly 150,000 Canadian students. We have also surveyed faculty and administrators in the United States multiple times about their experiences with teaching and learning during the pandemic. Most recently, we have returned to interviewing faculty across Canada to learn more about their hopes and fears.

We heard that many of our students and colleagues are anxious, tired and disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Students and faculty recognise that the pre-pandemic “normal” wasn’t optimal. It was simply the status quo, the default, that students and faculty were living with.

What faculty and students hope for is that their colleges, universities and governments support them as they seek to carry forward what they learned and experienced during the pandemic. They are hoping the lessons of the pandemic aren’t fleeting. Some of these lessons appear below.

Return to normal: What should we carry forward?

1. Teaching and learning innovation

Regardless of how a course is delivered — online, in-person or in a hybrid fashion — faculty noted that they hoped to carry forward various teaching and learning innovations.

Such innovations include things like the ability to invite other experts to their courses for virtual appearances as lecturers or discussions with students. Others include continuing to develop new assessment practices, in favour of more frequent and authentic evaluations of learning rather than tests.

2. Greater support

Faculty and students want greater support from their institutions and from government that will help them maintain physical and mental health during and after the pandemic.

Both students and faculty noted that commitments for predictable and consistent funding can alleviate concerns and anxieties about the challenges that they foresee. To put this into perspective, a Statistics Canada survey of approximately 100,000 students from May 2020 identified that 67 per cent of respondents “were very or extremely concerned about having no job prospects in the near future.”

Faculty expressed anxiety about workload, program cuts and precarious academic work, hoping that they can be involved in discussions about these issues and about campus safety.

3. Flexibility

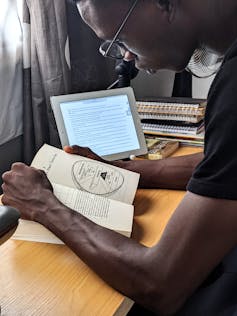

Students appreciated flexibility in deadlines when they were facing uncertainties in their lives. Source: Pexels/Oladimeji AjegbileOne idea that emerged consistently in both our work and the work of other researchers is the value that flexibility affords students and faculty. Students, for instance, appreciated flexibility in deadlines, when they were facing uncertainties in their lives outside their studies.

Faculty whose institutions supported them in working remotely expressed gratefulness for such flexibility. Some also appreciated being able to approach their courses with flexible designs that supported student learning (for example, shifting lectures to pre-recorded sessions and using real-time meetings for workshops). Flexible approaches to teaching and learning will likely help colleges and universities grapple with future local and global threats like climate change.

4. Trust and compassion

While education is an endeavour that involves establishing standards of learning and evaluation, it is also one that involves humans, with all of life’s unpredictability and variation. In approaching education with a humanizing lens, faculty and students hope that institutions and governments do not lose sight of the trust and compassion that was extended to them during the pandemic.

In practical terms, trust and compassion may translate to rethinking assessment practices that are grounded on mistrust, such as using surveillance technologies for online exams. It may mean trusting faculty to determine the best assessments for their courses. For example, a faculty member told us they felt what’s needed is “culture shift” towards trusting students, away from an “adversarial kind of relationship” that assumes everyone’s cheating.

5. Focus on equity

The pandemic has brought to light the many gaps that students of varied socio-economic and demographic backgrounds face, such as inequitable access to technology and private study spaces, as well as inequities in having their basic needs met.

Students and faculty are hopeful that institutions and governments continue to take action on addressing inequities. Some ideas offered include the purposeful design of courses to accommodate different people’s needs, and institutional supports to enable broader access to programs and resources.

Rather than regressing “back to normal,” what our research highlights is how students and faculty hope for a better future — better than the one dominated by COVID-19, and better than the status quo that existed prior.![]()

George Veletsianos, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Innovative Learning and Technology, Royal Roads University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.