A New York City mother said she kept her son in remote schooling during the pandemic because she believes city education officials “lie a lot.” “These buildings are old and don’t have proper ventilation,” she explained to journalist Melinda Anderson. “They don’t have the supplies they need, and they don’t even have nurses.”

One of the nation’s teachers’ union leaders has also heard repeatedly that teachers too often haven’t seen soap or running water in school bathrooms. Teachers in Chandler, Arizona, accused their school board of breaking promises to close schools if COVID-19 became widespread locally.

A New Jersey mother wanting her child to attend school in person “lost a lot of faith in the district” and may send her child to Catholic school in the fall of 2021 after she experienced repeated, unpredictable openings and closings in her local public school.

All of these situations represent cases where trust broke down between parents or teachers and the schools in their communities. While much news coverage and debate during the pandemic has been about things like wearing masks and adequate spacing between students and ventilation, the topic of trust seems to get much less attention.

As an education historian, I believe that if the importance of trust is continually ignored or overlooked, it could have serious consequences for the nation’s schools.

Racial factors at play

Trust in school safety varies among communities.

In national polling, white parents were far more likely than other parents to favor sending their children to in-person schooling during the pandemic. The stark racial differences should not be surprising given that Black and Hispanic communities have been more severely affected by COVID-19. But pandemic vulnerability is not the only difference.

A parent leader in Memphis, Tennessee, told a reporter of her community’s reaction to the idea of returning students to school: “For generations, these public schools have failed us and prepared us for prison, and now it’s like they’re preparing us to pass away.”

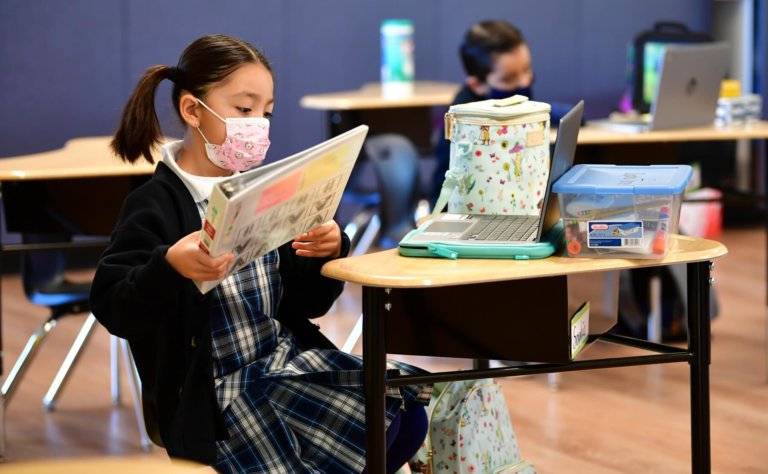

Asian American parents in Chicago, New York City and Fairfax, Virginia, have also been more likely than those cities’ white parents to keep their children in remote schooling. A key factor has been a desire to protect their children from anti-Asian attacks that have escalated during the pandemic. These attacks are widely believed to be a byproduct of the blame that President Donald J. Trump has heaped upon China as being responsible for the spread of COVID-19.

How should these different levels of distrust from different segments of society be understood?

Elements of trust

Asian American parents in certain cities are more likely than those cities’ white parents to keep their children in remote schooling. Source: John Moore/Getty Images North America/Getty Images via AFP

The key is relational trust, a term coined by sociologists Anthony Bryk and Barbara Schneider. Relational trust deals with how much people see unity of purpose around them. Do they believe that the people they depend on have the right intentions, essential competence and integrity to work for the common good?

In schools “that operate in turbulent external environments,” teachers and other school staff risk their professional careers and sense of self on the job. Parents risk their children’s and families’ futures. Given the high stakes involved – that is to say, people’s health and safety – relational trust is essential.

In a pandemic, it has become more obvious that educators and students often work and study in buildings where plumbing – and especially heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems – need major repairs.

The physical condition of schools is critical. A wealth of research has shown that the school environment can influence student academic achievement, as well as student health.

But with the pandemic – and news reporting of failure by the federal government and many state governments – relational trust is one of the casualties.

White House push for teacher vaccinations

The Biden administration addressed relational trust when it pushed states in early March 2021 to prioritize teachers and other school staff for vaccinations. By the end of the month, all teachers were eligible for vaccines in 46 states and the District of Columbia.

Americans agree with an emphasis on vaccinating educators: in a February national poll, 59% of surveyed American adults said that schools should wait until all teachers had the chance to be vaccinated before completely reopening.

State officials can ask whether key decisions might erode relational trust. For example, should students who are learning remotely be required to step into a school for achievement testing? The Biden administration is not waiving all testing requirements, but it is discouraging the idea that students must “be brought into school buildings for the sole purpose of taking a test.”

In contrast, Florida Commissioner of Education Richard Corcoran has decreed that all students must take tests in person. Parents want state and school officials to respect their judgment of whether to send children back just for tests. If education leaders want to build more relational trust with parents, it will include letting them manage risk to their children.

Investing in safety

Beyond the 2020-21 school year, relational trust can be built if public money is invested in what will keep students and staff safe.

The Biden administration’s infrastructure plan has one component of this: US$45 billion to remove pollution sources such as lead-lined pipes from schools and day care centers.

With the pandemic focusing attention on the dangers of being inside, remediating lead, asbestos and other pollution sources should help build relational trust. The lead crisis in Flint, Michigan’s water supply is only the most visible example; tests found elevated levels of lead in 37% of schools where drinking water was tested.

Addressing facility conditions also requires giving more authority to employees to raise environmental and health concerns. In Chicago, for example, a new labor contract includes a provision for school safety committees.

Ways to build trust

The theory of relational trust suggests schools need to build respect and bring the community into school operations and decision-making. Bringing in the community can look as simple as a bilingual outreach program to parents around college attendance or a program to hire parents as family liaisons to the school district. Or, with organizations that specialize in this work, education leaders can bring schools, parents and community members together to define and solve shared problems.

It may sound squishy to assume that parents and communities bring unique wisdom. But even done imperfectly, this kind of convening helps to build relational trust.

As researchers hear from parents, direct experience with schools that respect parental perspectives changes their relationship with schools:

“I have more coraje (courage) now” in raising concerns with school officials, one parent explained to educational leadership scholar Susan Auerbach.

“Here you come and how can I say it, with confianza: There is trust here,” another parent told education professor Ann M. Ishimaru and her colleagues. “We already know this place and other teachers help us more with the children.”![]()

Sherman Dorn, Professor of Education, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.