When a language dies, the identity, history, and a whole way of life go with it.

Take Tandia, a language used in West Papua, Indonesia, for example. It was declared extinct in 2024; the last Tandia speaker passed away in 2002, and their children no longer understand the language.

In Pakistan, a similar story is happening with the Punjabi language. Despite being the most widely used language in the country, it’s slowly fading out of public and academic life, replaced by Urdu, the national language, and English, the official language, respectively.

This has resulted in a major educational crisis.

“While studying at the University of the Punjab, I was surrounded by incredibly smart people,” says Fatima Ebadat Khan, an MS in Education graduate and educator in Pakistan. “But they were struggling. Not because they weren’t capable, but because the programme was in English.”

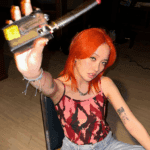

Khan was born and raised in Pakistan. Her grandparents migrated from Lucknow, India, to Lahore, Pakistan. Source: Fatima Ebadat Khan

An educator’s mission: Fixing a broken system

Pakistan was under British colonial rule for over 150 years. When the country finally gained independence in 1947, it inherited more than just borders, it also inherited a foreign education system.

Today, most Pakistani schools and universities operate in English or Urdu.

“There’s no clear vision for education in Pakistan,” Khan says. “Policies are made by politicians or bureaucrats who don’t understand the classroom reality. It’s like a vehicle running without a driver.”

Khan, who was born and raised in Lahore, Pakistan — the centre for Punjabi speakers — was taught in English for her BS in Political Science and Media Studies at Lahore School of Economics and MPhil in Sociology at the University of the Punjab — two of the country’s top private universities.

While Khan herself had no issues with her studies, she noticed that many Punjabi or Urdu speakers were put at a disadvantage.

“The students around me were smart, but they were struggling to keep up with the English-medium system because Punjabi or Urdu was the only language they knew; it was eye-opening for me,” she says.

Thanks to her MS in Education, Khan is currently working in education policy and education for peacebuilding. Source: Fatima Ebadat Khan

And it wasn’t just that the programme was delivered in English — most of the teaching materials came from the West, resulting in a serious lack of representation and perspective from South Asia, especially Pakistan.

Realising this, Khan was determined to help resolve this issue, making it her personal mission to decolonise education in Pakistan and make it more inclusive and localised to improve the locals’ livelihoods.

Khan became an O-level world affairs (history and sociology) teacher and an A-level sociology teacher at local high schools. On the side, she worked as a research assistant at the National Curriculum Council (NCC), helping Dr Mariam Chughtai, the Director of the NCC, map out the K-8 curriculum in social studies.

While working towards making a change in the educational field in Pakistan, Khan knew she needed more in her arsenal to help her with her mission.

The answer? An MS in Education.

Khan was a Commonwealth Shared Scholar at the University of Bristol. Source: Fatim Ebadat Khan

Using an MS in Education as a key to unlocking new solutions

In 2022, Khan received the Commonwealth Shared Scholarship to pursue an MS in Education at the University of Bristol, UK.

While it might be strange to most — after all, Khan planned to decolonise the education system in Pakistan, so pursuing her studies in the country that colonised her nation might raise some brows — she had a sound reasoning for it.

Ranked #54 on the QS World University Ranking 2025, Bristol is one of the few institutions in the UK actively working on decolonising their curriculum.

“Many higher educational institutions and disciplines of study were created during colonial times and their curricula developed to match that world view,” writes the university on their website. “This has affected the way knowledge is produced, validated, and disseminated. Decolonisation is an active process of critical scrutiny of our curricula and teaching practices aimed at understanding this legacy and beginning the work of dismantling it.”

So, Khan’s programme — an MS in Education focusing on Policy and International Development — gave her the resources she needed to tackle some of the most pressing issues back home.

Her master’s thesis focused on how the Pakistani curriculum often preaches intolerance and exclusion of minority communities.

“I wanted to understand how we can reshape our education to reflect our history and experiences, not someone else’s version,” says Khan.

While at Bristol, she worked with the university’s library to include more books and resources written by minority scholars from Latin America, Asia, and Africa. She also helped the school run workshops that taught students how to create more inclusive and equitable research and writing.

One of the biggest highlights? Being a part of the Education, Justice and Memory Network (EdJAM), led by Dr. Julia Paulson, an associate professor at Bristol’s School of Education.

This international initiative brings together educators and researchers to find creative ways to teach about violence, conflict, and colonialism — all from a justice-driven perspective.

“EdJAM was one of the deciding factors for me to join the MS in Education programme at Bristol, and it was an honour to participate in it,” shares Khan. “It aligned with the research prospects that I had for my thesis during my master’s.”

With her MS in Education and experience abroad, Khan founded The Graduate Route and has since helped several Pakistani students to seek an education abroad. Source: Fatima Ebadat Khan

Building a better, more localised future for Pakistanis

Today, Khan, equipped with her MS in Education, is a researcher on the National Primary School Curriculum project at the Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP), a curriculum consultant for the Lahore Grammar School, and a member of the Futures of Education, a collaboration with Harvard’s Human Flourishing Programme that gets people worldwide to think in new meaningful ways about education and work together to create better learning opportunities.

She has also launched two passion projects.

The first is Miyan Mithu, a platform aimed at preserving and teaching the Punjabi language and culture to local Pakistani children.

Despite Punjabi being the most spoken language out of the other 14 available in Pakistan — 36.98% of the population speak it — it is often seen as a lower social status language, especially in urban Pakistan.

Parents feel embarrassed to speak it, so the next generation doesn’t learn it. Naturally, this means that the number of Punjabi speakers in the country has dropped, decreasing from around 44.15% in 1998 to 38.78% in 2017, according to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

However, the number of Urdu and English speakers in Pakistan aren’t great either. The Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS6) by the United Nations reports that the languages are spoken by only 0.01% of the population.

Still, these languages promise power and opportunity — but not without some contradictions.

“While Urdu is an official language and many are now learning it, it’s hardly used in day-to-day matters,” says Khan. “If you don’t speak it well, you’re automatically left out, especially when you want to get a good job. It’s unfair for those who grew up speaking Punjabi or any other local language.”

Through Miyan Mithu, she’s creating accessibility to resources for children to learn Punjabi and reconnect to their roots, hoping to ignite an interest in the language and prevent it from dying out.

Khan’s second venture, the Graduate Route, tackles another big issue — access to higher education.

“When I was studying abroad in the UK, I realised there were so few Pakistani students at overseas universities,” she says. “Most of the students in Pakistan didn’t know where to start looking for higher education abroad or how to find scholarships to fund their education.”

The Graduate Route offers mentorship and guidance to those who want to pursue higher education locally and internationally. They help with everything from applications to scholarship hunting.

Khan credits her time at Bristol for giving her clarity and motivation to launch these projects.

“Studying abroad really opened my eyes,” she says. “But more importantly, it showed me how few Pakistanis have the same opportunity, and I want to change that.”

“Pakistan is a post-colonial country. We’ve been independent for 77 years, but mentally and structurally, we’re still stuck in the colonial mindset. If we want to move forward as a nation, we need to start by reclaiming our education, which starts with our language, stories, and people.”