For many international students in the US, an American education can open the door to opportunities in the US or in students’ native countries. The transition to an American university, however, can throw many out of kilter.

Classrooms may be more engaging than what some students are used to. Here, students aren’t merely passive learners; they’re expected to speak up in class, share their opinions and work in groups. In some countries, eating in a classroom is taboo, but that’s not always in an American classroom.

These are just some of the things that Dr. Rajika Bhandari can relate to as a former international student in the US.

“The first few days were a blur of new tastes, smells, ideas, and learning — from savouring the fizz from a real Coca Cola to getting acquainted with the all-American chocolate chip cookie on the American Airlines flight that brought me into Raleigh, to gauging and understanding classroom dynamics in America,” she told Study International.

Bhandari came to the US as an international student back in the 90s. Today, she is a naturalised citizen. She is the founder of Rajika Bhandari Advisors, which offers data-driven and evidence-based strategic consulting and advisory services for global higher education institutions and governmental agencies, to name a few.

We speak to the international higher education expert and author about her time as an international student in the US and how her book can help others develop a deep understanding of what they are likely to experience by studying in the US.

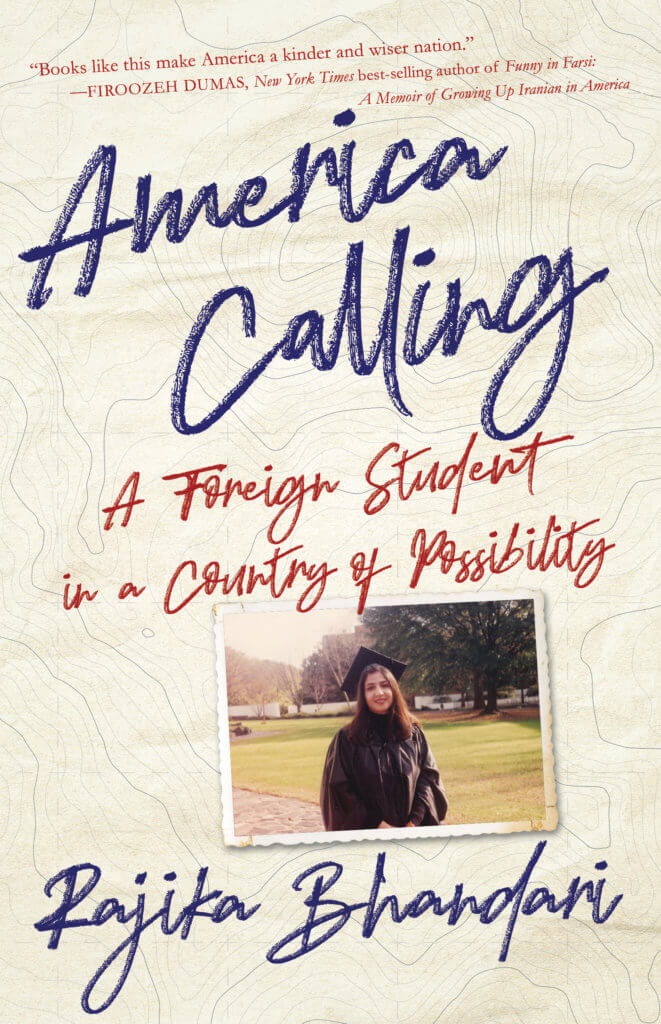

Bhandari completed her doctorate at North Carolina State University. Source: Dr. Rajika Bhandari

Hi Rajika. Can you tell us about yourself? How did your interest in education begin?

I am a social scientist by training and most of my career has been spent as a researcher in the field of education, primarily international higher education.

I started out like many Indian students with an undergraduate degree in India, and then came to the US to study. Although I was initially studying psychology, I found myself drawn to the study of social and global issues and became interested in the role that education plays in global development, especially girls’ and womens’ education. The role of women and education in development and the impact that has on societies has always been a deep interest of mine.

Upon completing my doctorate in North Carolina, I made a conscious decision that I did not want to remain in academia or what I perceived as the “ivory tower,” so I decided to work outside the university sector as a researcher in the field of education. I found myself researching domestic education issues in the US such as high school reform, parental involvement in education, etc. But the international and global piece was missing and kept beckoning.

After a failed attempt at moving back to India, I deepened my roots in America and over time became an expert in studying the movement of international students around the world. The subject matter and issues also resonated deeply with me as it had been a lived experience for me, having gone to the US as an international student from India.

Tell us about your experience as an international graduate student in the US back in the early 90s. For instance, what were some of your fondest memories? Did you face any challenges that today’s international students in the US don’t, or vice versa?

This is a very broad question and one I tackle in-depth in my book! I arrived in North Carolina to attend North Carolina State University. Even though I was coming from a large, cosmopolitan city like Delhi, there was a lot to learn and absorb, especially because the American south was so different from what I knew or understood about the US.

The first few days were a blur of new tastes, smells, ideas, and learning — from savouring the fizz from a real Coca Cola to getting acquainted with the all-American chocolate chip cookie on the American Airlines flight that brought me into Raleigh, to gauging and understanding classroom dynamics in America, and beginning to realise that all the fundamentals of education I had grown up with in India had not prepared me for the culture of teaching and learning in an American university. In the years to come, the experience of coming to the US as a student would stretch my boundaries and challenge my thinking and assumptions in ways I hadn’t imagined.

There was a whole village of people who were very supportive during my early years in the US, ranging from my academic advisor who understood the large educational and cultural gap I was experiencing and helped me settle in, to two dear American classmates and friends who treated me like family — donating furniture to me for my student apartment, bringing me a real Christmas tree on my first Christmas in the US, and showing me the ropes of everyday life in America. And then there was my support system of other Indian students just like me who were trying to adjust to life in the US the same way I was.

International students today are far more savvier and better prepared than those of my generation: they are up-to-date on American popular culture, thanks in part to the internet and the accessibility of information.

Further, as the US has itself become a more diverse society, today’s international students see others around them who are from their country and culture. However, what has not changed over time – or from when I was an international student – are the academic, cultural, and immigration challenges that international students continue to face. Another challenge that has persisted – or perhaps worsened over time – is the sheer unaffordability of a US degree and the financial barriers that many talented and aspiring international students face.

Some things have not changed since Bhandari was an international student in the US, including “the sheer unaffordability of a US degree”. Source: Dr. Rajika Bhandari

You recently published your book, “America Calling: A Foreign Student in a Country of Possibility”. What inspired you to write it?

I have worked in the field of international education for many years and during this time came to realise how little the American public knows about international students — who they are, where they come from, what their experiences are. Even though there are almost one million such individuals from over 200 countries who study in the US, there is no broader understanding of the value that they bring to American society and are presented with educational and immigration hurdles every step of the way.

I want the book to be a glimpse into the lives of these students and potential future immigrants, to add a face and voice to their stories. I want Americans to understand how important their colleges and universities have been in connecting them to the rest of the world and that the future of the country is at risk if the world stops coming to American institutions.

If it were not for this type of exchange, the US would not have a Kamala Harris, a Barack Obama, or writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. These issues became even more urgent under the previous administration, when there was an onslaught of damaging proposals — including the infamous travel bans — which made America feel very unwelcome to international students.

As someone who had watched this from the sidelines, albeit as an expert, I knew I had to speak up and share my story and that of others on what being an international student and future immigrant feels like.

Finally, even though the book is focused on the US, its messages and themes apply to other countries like the UK, Canada, Australia and others that attract large numbers of international students.

In her book, Bhandari shares her personal story of the trials and tribulations of an international student in the US. Source: Dr. Rajika Bhandari

Your book received plenty of praise, including from those in the HE sector. What do you think international students can gain from reading it?

I am delighted that the book has also resonated with students and many in our sector have described it as a “must-read” for both international and US students.

What current and future international students can gain from the book is a deep and honest understanding of what they are likely to experience as an international student in the US and how to better prepare themselves for a journey that can be both transformational yet challenging in its own way.

The book can also help international students understand the role they play as unofficial ambassadors for their countries, helping connect the US and other countries through education, cultural exchange, and innovation.

My hope is also that the book will inspire international students everywhere to learn to advocate for themselves, for their academic and cultural needs, and to know that they have agency as individuals and as an important population of students on a campus.

Lastly, the book will also prepare international students for the difficult choices they will need to make in the future as they consider issues of where to live and work, issues of brain drain, and how best to be global citizens regardless of their geography.