Getting a master’s degree in education policy can lead to a rewarding career, one that positively impacts students and their development. This is what Samuel Isaiah had in mind as he applied for the Fulbright scholarship: a chance to make a bigger-scale impact by educating the Orang Asli (an impoverished indigenous minority group in Malaysia),

When Isaiah completed his bachelor’s degree in 2011, he had not set out to teach in a rural primary school, where many Orang Asli children attend. Posted to Runchang, deep in the country’s heartland, he would discover his future calling.

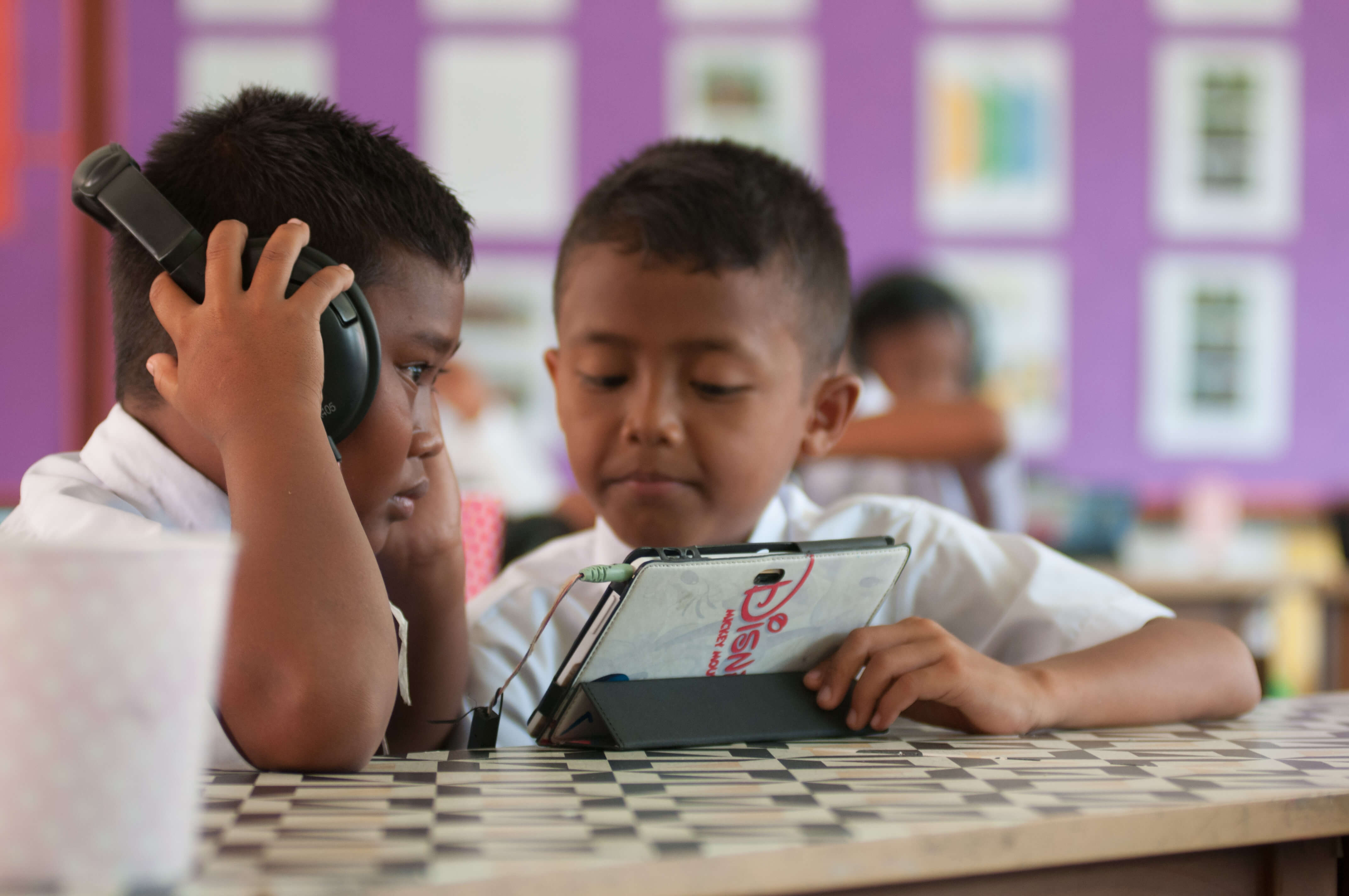

The root of the problem was obvious here: people didn’t care enough to try. Isaiah made an effort to bond with his indigenous students and understand their points of view. He set up a crowdfunding project to create a fully-equipped classroom with tablets and computers so the Orang Asli children could learn English as any other urban pupil would.

Recognition followed. Isaiah won the Best Teacher Award 2018, Best Innovative Teacher 2018, the Star Golden Hearts Award 2019 and the National Hero Teacher Award 2019. He was also a finalist for the Global Teacher Prize.

Today, Isaiah has bigger goals. He plans to empower other indigenous communities in Malaysia with the help of like-minded teachers through his “Cikgu Kickstart” (translated to “Teacher Kickstart”) project. Below we talk to this inspiring student and teacher about his experience and future plans:

Tell us about your Fulbright Scholarship. What made you want to apply?

I knew I was there teaching the Orang Asli community for a reason and I knew I had to do my best to help them. Every year, I saw myself doing different things, improving and networking with different individuals and organisations. But after eight to nine years, I realised I hit a plateau.

If there is no sustainability, for instance, when my kids leave my class or principles of teaching and go to another school, it all goes back to square one. One of the biggest problems with the Orang Asli community or an indigenous education is that the school dropout rates are extremely high.

Isaiah set up a crowdfunding project to create a fully-equipped classroom with tablets and computers. Source: Samuel Isaiah

Here, I realised that for me to be able to bring significant changes and make a big impact, it has to be holistic. I decided to apply for a scholarship so I can learn and come back with more of a capacity to help children and contribute to policy-making in general.

Where did your love for teaching come from? Is there a personal story behind this?

I think my journey to teaching was quite a confusing one because I never planned on it. I was in a science school so I was inclined towards fields like engineering and medicine. I only developed a strong sense of love and passion towards languages and culture later on.

My parents were not wealthy so they couldn’t afford to send me to private colleges or institutions. My only option was to go to a public uni. I opted to teach English as a second language in this teacher’s college in 2005 — the closest I got to learning about languages.

Even then, when I was exposed to the theories of Western methodologies of teaching and I still did not find any interest in it. I was very lost and did not know what I was doing — like being actively involved in a band and doing a lot of side stuff.

Isaiah was also a finalist for the Global Teacher Prize. Source: Samuel Isaiah

I wanted to plan my career to get my master’s done and make a leap towards higher education, doing a PhD or something but life had different plans for me. I was sent to a high-need school in a rural area in Pahang. That was when my whole view of what teaching is and what it’s for started to develop. I’ve got my students, my children and the Orang Asli community to thank.

Walk us through the difference between teaching and pedagogy. Give us an example and why you think it’s important to instil different methods.

So, I grew up in public school and the common notion for teaching there is for the teacher to come to class and give you homework or lectures. Nobody gets to ask questions, you’re not allowed to speak — that was the understanding of discipline and learning.

At the end of the day, the month, or six years of education, you sit for a major exam and move on. I noticed this system did not work on my students, mainly because education was not something meaningful for them.

So I started looking at incorporating aspects of project-based learning aspects of experiential learning which is engaged learning instead of just hoping to inspire children. I had to create meaning with education so the children would want to be involved. This came in the form of various interventions like music, technology, nature, and so forth. All these interventions of teaching and learning practices were kind of like pieces of puzzles coming together to form meaningful experiences for the children.

“I will always be trying to make a difference and challenge the status quo to help children,” Isaiah says about his future plans. Source: Samuel Isaiah

Tell us more about your career trajectory with Edufication and Cikgu Kickstart.

Edufication launched an innovation competition called, ‘Cikgu Kickstart’ Awards in partnership with Teach For Malaysia (TFM); an organisation that mobilises leaders for the empowerment of education and PEMIMPIN GSL; an organisation that implements professional development programs for the improvement of school leadership. This is funded by YTL Foundation and ECM Libra Foundation.

It’s a platform by teachers and for the teachers because a lot of times, organisations out there are not run by teachers along with a lack of critical discourse in education in Malaysia. These issues should be critically discussed. One of the aspects we needed to help was to mediate learning loss that has happened because of the pandemic — a big issue. We thought the best way to mediate the learning loss was to empower teachers.

We opened applications in March this year, where teachers submit projects and interventions they want to implement to help with learning in their school and community. Some were related to sport, some to mental health, and so on.Cikgu Kickstart is basically giving three finalists funds to begin their projects (15 finalists will be given seed funds where three winners will receive 6,000 ringgit each and the remaining 12 2,000 ringgit each), then we give them training so their small projects have a bigger impact, and lastly we network these pitches to industry leaders — that’s where the money is. The last phase of this kicstart (happening May 22) is a live pitch session, a sort of shark tank thing where we bring teachers directly to industry leaders.

“I realised that for me to be able to bring significant changes and make a big impact, it has to be holistic,” Isaiah says. Source: Samuel Isaiah

What more do you think should be done to help these communities get the education they deserve?

The Ministry of Education here is on track to progress, but I think what needs to be done is to give the Orang Asli community a voice. They need to be involved in the decision-making because organisations, ministries and whoever it is come in and try to change their livelihoods.

Making sure they’re centralised gave them perspective because I was doing something with them, not for them. We often leave out the identity and the voice of these Orang Asli communities. We need to celebrate their culture and identity.

When I was in school, I never learned anything about these communities so we need to create awareness about their identity and culture. We need to reimagine how we celebrate their identity on a national scale because we have this Messiah complex where we think we come in and save them from their underprivileged culture which is ridiculous.

Tell us more about your time abroad at the University of Albany.

So I completed two semesters at the University of Albany and decided to return to Malaysia in June last year when the pandemic was at its peak. My funders — the US Department of State — initially allowed me to stay in New York for one semester but this disrupted my plans.

Fortunately, they understood and have allowed me to complete my final semester in Malaysia. So that is what I’m currently doing.

Cikgu Kickstart is Isaiah’s project where he plans to empower and fund creative projects by public school teachers. Source: Samuel Isaiah

What advice do you have for students who aspire to go abroad under scholarships?

I had a compelling story and I think this is probably what most candidates don’t have when they apply. Instead of just a story to tell, I had a purpose of why I started something and worked on it. People have come to me for advice when they want to apply for scholarships and although they could identify issues in whatever they were doing, they never knew how to answer when I asked them: “What did you actively do about it?”

When you’re applying for international scholarships, this is what they look for: candidates with leadership qualities, passion, aspirations and who want to make a difference on a larger scale. Instead of looking at it as an academic opportunity to make your CV look good, they want genuine people who are honest with what they’re planning to achieve.

At the same time, you’ve got to be academically equipped and smart as well — all these aspects need to come together in a convincing narrative. My experience was a challenging one in a good way. It gave me opportunities I never had before and made me feel capable in policymaking and policy design. For example, with criticising policy, I started looking at higher education policies and the financial aspects of education in general along with the sociological aspects as well.

“Once you’re a teacher, you’re always a teacher,” Isaiah says. Source: Samuel Isaiah

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

I don’t really know if I’ll be teaching or not, but I will always be trying to make a difference and to challenge the status quo to help children. I’ve been actively looking at the opportunity to expand what I can do to create a bigger impact and change.

I have to look at the sustainable side of this and not restrict myself to the confines of teaching. I will still be in education for sure. I’m leaving the window open for the betterment of the community.

Lastly, what is one thing you missed from home while in the US and how did you substitute it?

Well, on a personal note, I missed my family a lot. I planned to bring my wife with me but because of the pandemic, that didn’t happen. When it comes to my career, I missed the kids the most.

Once you’re a teacher, you’re always a teacher. I was with those kids for 10 years before uni from morning till evening — speaking to them, creating lessons for them and playing music with them. I brought that to uni — my different perspectives stood out from my classmates and my professors really appreciated that.