You might think that if you stop using a language after studying it at school, you will end up forgetting everything you knew. But this isn’t true. Language knowledge will stay in your brain for decades.

In 2022, around 25,000 A-levels and around 315,000 GCSEs were taken in a modern foreign language. This means that language GCSEs taken have fallen by more than 40%, and A-levels by around 25%, over the past 20 years. Between 2014 and 2019, entries to modern language GCSEs fell by 19%.

This is a worrying trend, not least because learning a language is valuable in and of itself. Among the many benefits are better performance on general standardised tests and a boost to your wage.

There is another reason why studying a language at school will serve you well. As my new research shows, the knowledge you acquire in a foreign language appears to be astonishingly stable over long periods of time.

A similar finding was reported almost 40 years ago. The psychologist Harry P. Bahrick carried out an investigation of some 600 Americans who had learned Spanish in high school up to 50 years previously. While Bahrick found a small amount of loss between the third and sixth year after learning had ceased, knowledge appeared stable for decades afterwards.

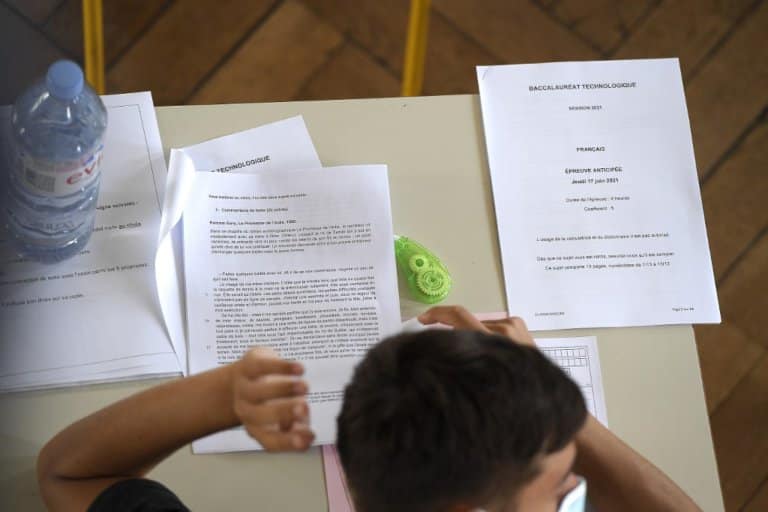

Results from a study show that language learners retain around 70% of the vocabulary they had learned after 25 years, despite not having used the language at all. Source: Jean-Christophe Verhaegen/AFP

Holding onto knowledge

Learners retained around 70% of the vocabulary they had learned after 25 years, despite not having used the language at all in the interim.

In comparison, a similar study of the retention of knowledge of high-school mathematics found that, unless participants continued to study maths in college, their performance on questions for high-school algebra and geometry indicated they had forgotten pretty much everything.

My colleagues and I recently carried out a similar study on the retention of foreign language knowledge. We asked 491 participants who had taken French GCSEs or A-levels up to 50 years ago to complete a test of French vocabulary and grammar knowledge. We also included a detailed survey on their use of French in the interim period, as well as looking at other factors, such as whether they had enjoyed studying French, and how successful they had been. We excluded anyone who continued studying the language later, for example at university.

Our findings were unambiguous and startling. We found no loss at all in their knowledge of grammar and vocabulary. In other words, participants who had taken their exam decades ago and not used French since then performed at the same level as those who only took the exam a few months ago, and as those who did, on occasion, use French.

This finding may seem even more surprising and counter-intuitive than Bahrick’s original results. After all, we know – or think we know – that if you don’t use a skill, you’ll lose it. Why would language be different from anything else?

The answer probably lies in the way in which we acquire, remember and use language.

When you learn a foreign language, you build a similar net, which partly overlaps with the one you already have in your native language. Source: Philippe Merle/AFP

How your brain works

Some parts of language (mainly the vocabulary) are memorised in the same way as facts, rules of algebra, dates, names and so on. This memory system is indeed vulnerable to erosion. Other parts, though, like grammar, are learned in a way that is much more similar to riding a bicycle. We use the part of our brain that is good at remembering rules and sequences through frequent repetition, so grammar becomes more like a reflex, and that kind of knowledge resists forgetting.

What’s more, your brain does not have a distinct part labelled “English” and a separate part labelled “French”. Rather, think of language as a very complex, responsive net, and that every time you use a word, you are touching the net.

Every time you touch one part of the net that point lights up with energy. However, this energy also spreads to all the areas of the net that are connected to the bit you are touching – words that sound similar, words that mean similar things, words that are often used together with the one you are touching.

When you learn a foreign language, you build a similar net, which partly overlaps with the one you already have in your native language. If, at some point in your life, you learned that “apple” in French is “pomme”, then that word will receive a small amount of stimulation every time you use the English version – and even more so if the two words happen to sound similar, such as English “banana” and French “banane”. This stimulation is what prevents the language from eroding entirely.

Of course, this does not mean that you can simply start chatting away in perfect French decades after your GCSEs. What it does mean is that, if you decide to return to it, you don’t really have to painstakingly re-learn the grammar you were taught back then – the likelihood is that it is still in your brain and only needs tickling a bit to emerge.

One of the great findings from our project was how many people felt that their language skills came flooding back during some minor emergency on holiday, like lost luggage or a broken down car. This also suggests that our brains remember the languages we have learned, and just need a bit of help bringing them back to the surface.![]()

Monika Schmid, Professor of Linguistics, University of York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.