The German Academic Exchange Service, or DAAD, has uncovered the colossal gap between demand and supply of scholarships for Syrian refugees enrolled at German universities.

The German international education support organisation has revealed that 271 Syrian students have been awarded a scholarship this academic semester, accounting for less than one in 18 of the total 5,000 applicants.

Approximately 200 scholarships in the ‘Leadership for Syria’ scholarship programme are being paid for via the Federal Foreign Office. The further 71 are being funded by the federal states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Baden- Württemberg.

Germany: 5000 applications received for 200 scholarships for Syrian refuges. https://t.co/9QoQeEQ0zF #highered #SyrianRefugees #Germany

— UniversityWorldNews (@uniworldnews) December 1, 2015

Syrian nationals who had already fled to Germany were invited to apply for the scholarships, along with others in the region, predominantly from places like Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Turkey and Egypt, according to Dr Christian Hülshörster, director of scholarship programmes for the DAAD.

“We received about 5,000 applications, most of them electronically, with about 500 applications handed into our offices handed in to our offices in the region,” Hülshörster told University World News.

Over half of the application (58%) came from prospective students still inside the Syrian border, while a quarter (25%) had already made it to Germany, whilst all remaining applicants (17%) derived from Syria’s neighbouring countries.

“The key challenge was to cope with the extremely high number of applicants and organise a fair selection procedure, based on DAAD’s high quality standards,” said Hülshörster. “For students coming from Syria to Beirut, we had to provide documents to enable them to cross the border.”

After receiving the applications, the universities began the pre-selection process. Five hundred potential candidates were invited to personal interviews in Bonn, Amman, Istanbul, Beirut, Erbil and Cairo. A ‘travelling committee’ of German academics who covered all the relevant disciplines were sent to manage the interviews.

“Successful candidates then had to apply for visas – and last but not least we had to find them places at German universities and organise language classes,” said Hülshörster. “In some cases, this has been relatively easy; in other cases we really had to discuss in length with the generally very supportive German universities which previous qualifications were transferrable.”

Refugee #Scholarship Apps now accepted for Jordanian universities: https://t.co/BIX4P0YRb7. Thanks to the work by @DAAD_Germany @giz_gmbh

— PRME Secretariat (@PRMESecretariat) November 25, 2015

The final decision was based purely on academic performance, and 200 students were awarded Foreign Office funding, plus another 21 scholarships donated by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Research of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Furthermore, the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of Baden- Württemberg supplied funding for 50 scholarships for Syrians already in the region.

Hülshörster emphasised that the Leadership for Syria programme is not only targeting refugees, claiming: “The purpose of the programme is helping to educate and train a future elite of academics who will participate in the rebuilding of Syria one day.

“Scholarship holders therefore have very different backgrounds – some of them have fled their homes for Lebanon or Turkey, others have already been in Germany as students – with the majority still in Syria at the time of application.”

With the Leadership for Syria programme, along with a separate annual DAAD programme that will fund 50 Syrians across all areas of study set for 2016, the German organisation provides living evidence of how universities can support the youth of Syria as they hope for a better future.

“German Minister of Foreign Affairs Steinmeier has said that ‘we cannot afford a lost generation in Syria’ – and that is what this programme is all about,” said Hülshörster. “In order to continue our effort, we have teamed up with partner agencies from the UK, France and the Netherlands in order to apply for European funding, setting up new scholarship schemes for Syrian refugees.”

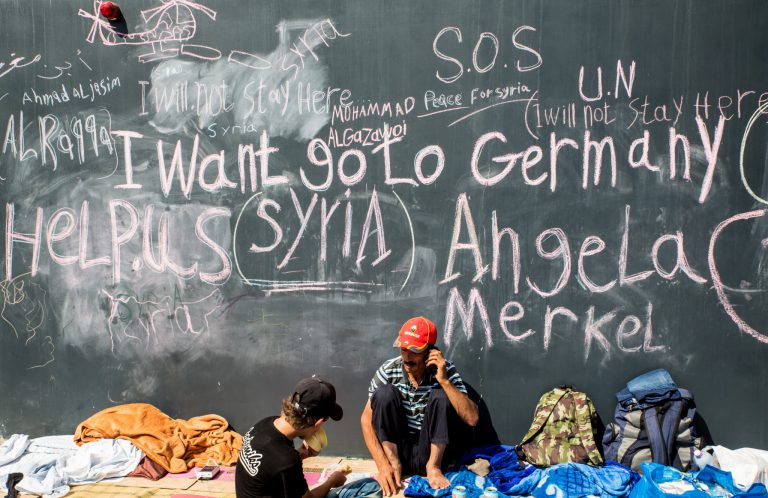

Image via Shutterstock.