In 1880, Columbia University’s Department of Political Science was founded as the first of its kind in America. Since then, it has become one of the largest of the Ivy League’s political science departments and one of the nation’s most acclaimed in every subfield of the discipline. Columbia political science scholars teach us about the psychology of leaders as well as of voters; the consequence of civil war and peacekeeping; the effects of spreading political misinformation, changing media consumption, and increasing education; and how democracies change, backslide, and, sometimes, die. The department also works at the forefront of methodological innovation, with a deep understanding of the opportunities and challenges that the new world of data has created.

The MA program in Political Science is embedded in the intellectual life of the department. Students learn about ground-breaking methods and theories directly from the same scholars who created them, and training occurs not only in classes, but also in co-curricular workshops and during the multiple interactions outside classes.

“In the past years, the program has developed both academically and professionally to guide our students through rigorous training as well as help them find a meaningful job after,” says Chiara Superti, MA director. “We aim to give our students the tools to understand, investigate, and shape the political dynamics surrounding us. Several of our students have gone into top-tier PhD programs and are continuing on the academic path. Others have started careers in the field of media, non-profit organizations, and government, to name a few.”

To give you a flavour of the interesting questions discussed in the department, we have chosen a few to share here with you.

How do we change political culture? Can it even be accomplished?

Patriarchy, inequality, and injustice are still today ingrained in the political cultures of countries across the world. How can we change these deeply rooted beliefs about the role of women in society, about the inequality of some minorities, or mistrust of others?

In a prize-winning article in 2009, Professor Donald P Green sought to find out how we can make a society less deferential to authority and more willing to express dissent. In the East African nation’s 1994 genocide, news reports stressed Rwanda’s “entrenched culture of obedience” when accounting for how the majority Hutu population killed over 800,000 civilians, primarily from the minority Tutsi group. Green conducted an assessment to determine the effectiveness of a radio soap opera program (called Musekeweya or New Dawn), in educating listeners about the underlying causes of violence, the significance of critical thinking, and the risks of excessive obedience to authority. After a year, communities of genocide survivors, Twa people, and incarcerated genocidaires still retained many of the same beliefs and attitudes. However, the program was discovered to significantly impact the listeners’ readiness to voice dissent and their approach to resolving communal issues.

This is one of the early examples of Professor Green’s dedication to understanding the psychological dynamics that influence citizens’ political attitudes worldwide. Today, he is the leader in the field of experimental approaches to studying electoral turnout and voting behaviors.

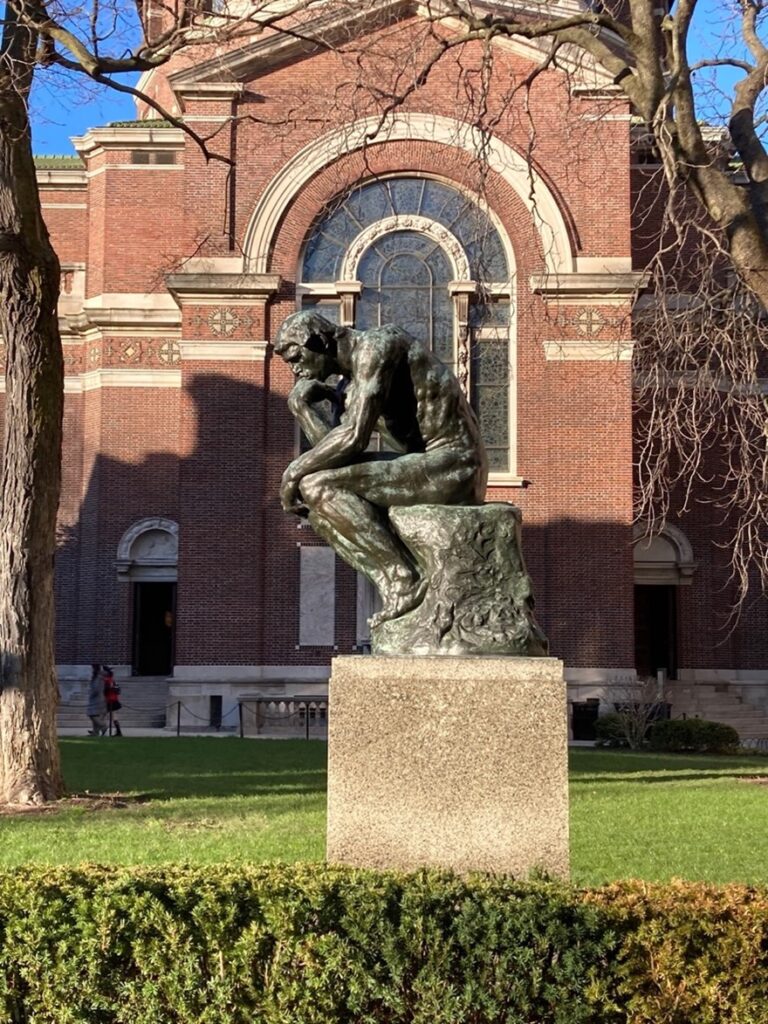

The Thinker (Le Penseur) by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), situated on the lawn outside Columbia University’s Philosophy Hall. Source: Columbia University, Department of Political Science

How does populism change democracy?

With the rise of populist leaders in many democracies worldwide, no question has been more pressing. Professor Nadia Urbinati addresses this in her book “Me The People.” She argues that populism disfigures representative democracy. The leaders become the only embodiment of the will of the people and speak directly to the people and on behalf of them. Politics become moralized and the battle for power becomes a fight between “good” and “evil”. In this context, the plurality of opinions, a vital component of democracy, dies. As the global trend of the electoral success of populist parties persists and the widespread use of the internet allows leaders to bypass intermediaries such as political parties and traditional media evermore, Urbinati’s work prepares citizens to understand the challenges to liberal democracies.

Low Library is a National Historic Landmark and the symbolic center of Columbia University. Source: Columbia University, Department of Political Science

Can political violence be stopped?

In the last 30 years the number of ongoing violent conflicts, the level of fatalities in violent conflict, and violence across the world has increased (Uppsala Conflict Data Program). Today more than ever, the work of scholars of war and peace such as Professor Page Fortna is crucial. In the 2008 book, “Does Peacekeeping Work?: Shaping Belligerents’ Choices after Civil War,” Fortna studies Sierra Leone, Mozambique, and Bangladesh, and shows how peacekeepers can “alter incentives, alleviate fear and mistrust, prevent accidental escalation to war, and shape political procedures to stabilize peace.”

Professor Fortna has also shed light on other forms of political violence, in particular terrorism. In a renowned 2015 article published in International Organization, “Do Terrorists Win,” she shows that terrorist groups are less likely to achieve their political goals than other groups using non-terrorist tactics.

Does TV matter in politics?

For decades, scholars and media personalities have thought about and discussed the role of news and political shows in influencing peoples’ opinions and political beliefs. But have we all missed an important piece of the puzzle? Assistant Professor Eunji Kim found that the answer is a resounding “yes”, we missed entertainment. Kim shows in her research how the entertainment media consumption of Americans shapes their perceptions of economic inequality, racial conflict, and electoral dynamics. Some of Kim’s ground-breaking work published in the prestigious American Journal of Political Science in 2023 demonstrates that reality shows such as “American Idol” and “MasterChef” with rags-to-riches narratives increase viewers’ beliefs about upward mobility in the United States (despite empirical evidence to the contrary).

Butler Library is home to collections in the humanities, history, government documents, social sciences, literature, philosophy, and religion. Source: Columbia University, Department of Political Science

How do authoritarian regimes really work and survive?

According to a report from Idea International (2023) in recent years, more countries have moved toward authoritarianism than toward democracy. A large share of the world population lives under a government that curtails human, political, and civil rights to some extent. Understanding the dynamics of democratic backsliding and authoritarianism’s inner functioning and survival mechanisms are fundamental research agendas that are taken very seriously by scholars in the Department of Political Science at Columbia University.

One of these scholars is Professor Timothy Frye, who has built his career studying Russia from the post-soviet era to Putin’s regime. In his latest book, “Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia” (2021), Frye demonstrates that the media and much scholarship have overemphasized the exceptionalism of Putin’s Russia. By comparing Russia to other non-democracies, Frye helps shed light on the mechanisms that dominate this modern autocracy. Through multiple empirical approaches to studying public opinion in Russia, he shows how Putin uses the strategies of many authoritarian regimes, from electoral fraud to internet propaganda to maintain political power and control of the state-society relationship. Frye finds that recognizing Putin “as an autocrat, and Russia as an autocracy like many others, may seem obvious — and yet doing so brings into sharp focus the inherent limits on his power” (Frye, Russia Beyond Putin, 2021).

To learn more about these and many other fundamental questions in the world of politics, check out the admission process to the M.A. Program in Political Science.