Thomas Benson once ran a small liberal arts college in Vermont. Stephen Gessner served as president of the school board for New York’s Shelter Island.

More recently, they’ve been opening doors for Chinese education companies seeking a competitive edge: getting their students direct access to admissions officers at top U.S. universities.

Over the past seven years, Benson and Gessner have worked as consultants for three major Chinese companies. They recruited dozens of U.S. admissions officers to fly to China and meet in person with the companies’ student clients, with the companies picking up most of the travel expenses. Among the schools that participated: Cornell University, the University of Chicago, Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley.

Two companies Benson and Gessner have represented – New Oriental Education & Technology Group Inc and Dipont Education Management Group – offer services to students that go far beyond meet-and-greets with admissions officers.

Eight former and current New Oriental employees and 17 former Dipont employees told Reuters the firms have engaged in college application fraud, including writing application essays and teacher recommendations, and falsifying high school transcripts.

The New Oriental employees said most clients lacked the language skills to write their own essays or personal statements, so counselors wrote them; only the top students did original work. New Oriental and Dipont deny condoning or wittingly engaging in application fraud.

Building on a model they pioneered for Dipont, Benson and Gessner helped New Oriental introduce its clients to U.S. admissions officers, linchpin players in the fast-growing business of supplying Chinese students a prestigious American education.

Beijing-based New Oriental is a behemoth. Founded in 1993, the company is China’s largest provider of private education services, serving more than two million Chinese students a year. Its shares trade on the New York Stock Exchange. The company generates about US$1.5 billion in annual net revenue from programs that include test preparation and English language classes. This year, about 10,000 of its clients were enrolled in American colleges and graduate schools.

Winning the trust of American college admissions officers is an important part of the business model. New Oriental’s counseling division – Beijing New Oriental Vision Overseas Consultancy Co – has centers throughout China and 3,300 counselors and staff. It typically charges students between US$1,450 and US$7,300 to recommend colleges and prepare applications.

“IT’S THE NATURE OF THE INDUSTRY”

![]()

A man enters the headquarters of the New Oriental Education & Technology Group in Beijing, China. Image via Reuters/Thomas Peter

A New Oriental student contract reviewed by Reuters states that its services include “writing or polishing” parts of college applications. The contract says New Oriental will set up an email account on behalf of the client for communicating with colleges, keeping sole control of the password. Several former employees said some students never even saw their applications because the company controlled the entire process, including submitting them to colleges.

The new insight into the business practices of Chinese education companies comes at a time when American colleges are relying more heavily on Chinese undergraduates, who tend to pay full tuition. Their numbers grew nine percent to 135,629 in the 2015-2016 school year and represent nearly a third of all international undergraduates, according to the Institute of International Education.

Helping Chinese kids get into U.S. schools has become a significant industry, with hundreds of companies having sprung up in China to cash in. These businesses often charge large sums for services that sometimes include helping students cheat on standardized tests and falsifying their college applications.

Ghost-writing applications for students is so common in China that some who do it speak openly about the practice.

“I wrote essays and recommendation letters for students when I worked at New Oriental, which I still do right now for my own consultancy,” former New Oriental employee David Shi told Reuters. “I know there is an ethical dilemma but it’s the nature of the industry.”

Many of the colleges participating in the New Oriental and Dipont trips said accepting travel expenses from the Chinese companies was appropriate, that they hadn’t been aware of the fraud accusations, and that none of the students received special consideration. Some said they have stopped or will stop participating in the subsidized trips.

Benson, in a statement responding to the fraud accusations, said: “There are many bad actors and bad practices in the world of admissions counseling, in both China and the United States. In every visit we have made to China, we have been strong advocates for the highest standards of honesty in the admissions process. We believe that we and those who have traveled with us have upheld these standards.”

New Oriental said its counseling division “prides itself on its longstanding commitment to education and the very high standards it has.” It added: “The company’s operations are governed by robust policies and procedures designed to guard against any unendorsed behavior by employees who are assisting students.”

Benson, who is 76 and speaks Mandarin, used to be president of Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont. He said he has had a lifelong fascination with China. He had a Chinese roommate in college and led a program for a spring term in China as a professor at the University of Maryland in the 1980s. Benson also is the co-founder of ASIANetwork, a consortium of about 170 colleges that promotes Asian studies.

“China has been in my blood and in my family history all the way through,” he said.

He said he first met Gessner, 72, about eight years ago. At the time, Gessner was a consultant to Shanghai-based Dipont, which runs international programs in Chinese high schools and college-counseling services that can cost a student more than US$32,000.

ESTABLISHING CREDIBILITY

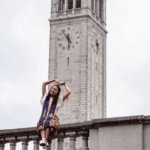

![]()

Stanford University’s campus is seen from atop Hoover Tower in Stanford, California, U.S. File photo via Reuters/Beck Diefenbach

Dipont executives said they wanted to help more students study in the United States. So, they initially hired Gessner, and later Benson, to help train guidance counselors and develop student exchange programs.

Beginning in 2009, Gessner and Benson launched tours and summer camps for U.S. admissions officers to meet Dipont students in China and advise them on applying to colleges. Benson said he and Gessner recruited the universities through contacts in secondary and higher education.

To establish credibility with the colleges, they said, they set up a New York-based non-profit called the Council for American Culture and Education Inc, or CACE.

“It was a more respectable way to work as consultants. It helped us to recruit colleges,” said Gessner.

The strategy worked. The early participants included admissions officers from such prestigious institutions as Cornell, Stanford, Swarthmore College, Emory University, and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Reuters reported in October that the New York Attorney General’s office planned to review the charity, which had failed to disclose its ties to Dipont in U.S. and New York State tax filings. The review could lead to a formal investigation if authorities find evidence that CACE violated New York law.

Reuters also reported that eight former Dipont employees had described how the company had engaged in application fraud, including writing essays for students and altering recommendation letters. Since the story, Reuters has interviewed nine additional former Dipont employees who gave similar accounts.

In a statement, Dipont said: “We will promptly and thoroughly investigate any credible evidence of any situation in which the company’s legal and/or ethical standards may not have been upheld by any of its employees, and will take appropriate action if we find that there have been lapses.”

In 2012, Benson and Gessner said, they were recruited as consultants by New Oriental and ceded control of CACE to Dipont.

Benson described their financial arrangement with New Oriental as “almost a carbon copy” of their deal with Dipont: the two Americans received US$50,000 for arranging each tour. They also set up another New York-based nonprofit, the Council for International Culture and Education, or CICE. Benson said New Oriental has no control over CICE.

The duo enlisted many of the same colleges that had participated in Dipont camps, and added some others, including Haverford College, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Florida. New Oriental covered travel expenses for tours to various cities in China.

THE COST OF ACCESS

![]()

Cigus Vanni, a retired high school guidance counselor, said it was “absolutely” unethical for colleges to accept the money. Image via Reuters/Mark Makela

To get the colleges to participate in the New Oriental trips, Benson and Gessner used the playbook they perfected at Dipont. Both Chinese companies paid airfare, hotel, and other travel expenses for each of the admissions officers whom Benson and Gessner brought to China between 2009 and last year. “They wouldn’t go otherwise,” Benson said.

The ethics code for college admissions officers doesn’t address the propriety of such arrangements. Cigus Vanni, a retired high school counselor from Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, said it was “absolutely” unethical for colleges to accept the money. He likened it to a “pay-for-play” scheme in which prospective Chinese students get special treatment. Many American applicants to elite U.S. colleges – which can receive five to 20 applications for each available slot – don’t get to directly interact with admissions officers.

“You’re giving these people direct access to college admissions officers that no one else has,” said Vanni, who serves on the admissions practices committee of the National Association for College Admission Counseling. “And there’s something expected in return for that.”

New Oriental touts the benefits of this access to prospective clients. In promotional material on its website, the company described how, during the 2014 tour, it arranged for one of its students “to have opportunities to have close contact with a Carleton admissions officer.”

The testimonial ends with the young woman receiving an acceptance letter from Carleton College.

Carleton admissions officers went on tours subsidized by New Oriental in 2013, 2014 and 2015 and participated in six Dipont-subsidized summer camps. Paul Thiboutot, Carleton’s vice president and dean of admissions, said the Northfield, Minnesota college was unaware of the New Oriental ad. He said Carleton is now reconsidering its involvement in such programs “and most likely will no longer participate.”

“We do indeed see ethical issues in accepting all-expense-paid trips from Chinese companies if these companies allegedly engage in college application fraud,” he said in an email.

Dan Warner, director of admission at Rice University in Houston, said when Rice agreed to send an admissions officer on a tour in 2014, it believed the trip was underwritten by CICE, not New Oriental. He said Rice probably wouldn’t have participated had it known of the company’s role. Benson said New Oriental’s role was made clear.

Olivia Qiu said she used New Oriental to apply to eight U.S. colleges in 2010. After completing a questionnaire, the counselors took over. “I didn’t write anything. They wrote everything for me,” she said.

Qiu ultimately didn’t attend any of those eight colleges. Before university, she took a job at New Oriental in Tianjin and said she wrote essays for students. Other employees, she said, wrote personal statements, supplemental essays, and recommendation letters. “Sometimes, the student didn’t even see (the application) before they submitted it” to colleges, she said.

She said she quit over ethical concerns. “I just thought that’s not right, that’s not how you help students,” she said.

FEELING “REALLY CONFLICTED”

![]()

New Oriental Education & Technology Group headquarters in Beijing, China. Image via Reuters/Jason Lee

A current New Oriental employee said he once falsified an entire high school transcript for a student. A former employee who worked in 2014 and 2015 compared New Oriental’s college application process to an assembly line: One person was in charge of signing a service contract with parents, another compiling a college list, a third completing the application, and a fourth submitting it to universities.

Alan Li worked on applications in 2012 and 2013 in Shanghai. He said he wrote personal statements and edited recommendation letters students had written about themselves. He said he would use material for essays from questionnaires the students completed but would invent stories if necessary.

Li said he initially felt “really conflicted”, but ultimately decided that a good student who was a “horrible writer” deserved a break.

By early this year, Benson and Gessner had stopped working for New Oriental and were focusing on new markets, including India, Sri Lanka and Africa.

But the duo hasn’t abandoned China. In June, CICE organized a tour for admissions officers from seven U.S. colleges on behalf of another Chinese company, EIC Group.

“I am getting a late start in putting out invitations for the summer 2016 China tour, primarily because we (CICE) have moved from New Oriental to a new Chinese partner,” Benson emailed an admissions officer at the University of Florida in March. “We were invited by EIC, a large, much more innovative Chinese organization to partner with them on a series of summer tours – boarding school, college, and graduate school.”

In addition to Florida, the schools included Colorado College, Cornell, Macalester College, Smith College, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the University of Rochester.

EIC Group paid CICE US$35,000, according to Benson, and promoted the tour with an advertisement on its website. “By ‘schmoozing and exchanging ideas’ with admissions officers, you are halfway to a successful application to a famous school,” said the Chinese-language ad. The ad disappeared after Reuters questioned the company about it.

A spokeswoman for EIC said the events were open to the public, and aimed to improve Chinese students’ applications. She didn’t respond to questions about the ad.

Benson said he hadn’t seen it. “That is really bad, horrible,” he said. “My goodness.”

– Reuters

Main image via Reuters

Liked this? Then you’ll love these…

China accused of ‘buying’ influence in Australia by channeling funds to universities

US, UK most popular destinations for China’s wealthiest students