In Beijing’s exclusive Haidian district, Zhao says she ploughs US$10,000 a year into extra classes for her eight-year-old in one of China schools, a leg up in the competitive scramble of modern China — and an advantage the state now wants to restrict.

As they scythe down oversized businesses, Chinese authorities say the vast tutoring sector has to turn non-profit, effectively wiping out the business models of education companies that have spun billions from the anxieties of China’s parents.

But last weekend’s edict by the State Council has drawn scepticism from Haidian’s parents, who are normally sure-footed as they plot their child’s path to university.

“Without extra classes, it might become difficult to keep up,” lamented Zhao, a 42-year-old mother giving only her surname, of the prospects of her child who is taking extra classes in Chinese, English and mathematics.

The move to non-profit status — and a ban on teaching core subjects on weekends and during holidays — aims to ease pressure on pupils and curb high education costs, authorities said.

But parents say those fine aims do not change the wider environment facing their children. “It still involves ‘involution’,” she added, invoking a tag used to describe the race to outcompete that ends up nowhere.

For China’s middle-class kids, that race starts as early as kindergarten — which must be bilingual for those who can afford it.

Analysts offer a partial explanation of the government’s motivations for taking on tutoring, a move that saw the share prices of listed education behemoths tank while their billionaire founders shed fortunes almost overnight.

In theory, taking some air out of the sector could ease burdens on a daunting part of child-raising: the huge cost of education. Many young Chinese cite education costs as a reason they are unwilling to have children.

But for parents in competitive cities, the idea of failing to provide the best is a non-starter. “I don’t think it’ll be particularly effective… you can’t stop one-to-one classes,” said freelancer Jin Song, 45, who has a daughter starting middle school. “Those who have a little more money will find a way.”

A parent surnamed Li, 45, told AFP his family moved a few kilometres when his daughter enroled in one of the China schools in Haidian. Source: Noel Celis/AFP

‘Chicken babies’ of China schools

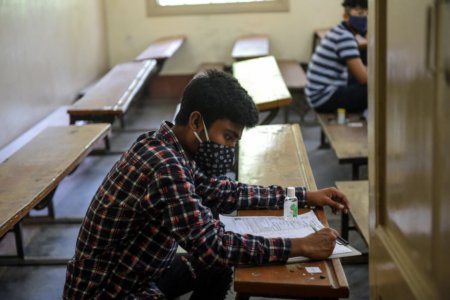

During a recent evening in Haidian — home to China’s elite Tsinghua University — teenagers shuffled to private classes over their summer break.

The pressure for both pupils and parents spikes further during “gaokao”, the notorious entrance examination for Chinese universities.

A parent surnamed Li, 45, told AFP his family moved a few kilometres within Haidian when his daughter entered junior high, renting a flat near one of the China schools so she could spend less time commuting.

Such is the state of competition that students juggling packed schedules have their own nickname — “chicken babies” — an expression that suggests stimulation into a hyperactive state after being “injected with chicken’s blood”.

But there is growing recognition that the costs of competition in China schools are preventing couples from having more kids — and thereby contributing to a demographic crisis.

School’s out? Tuition curbs pile on the anxiety for China’s parents https://t.co/xJWPreqcQE

— TOI World News (@TOIWorld) July 30, 2021

Over 90% of 4,000 parents surveyed sent their children to extracurricular classes and half spent more than 10,000 yuan ($1,540) on lessons, according to a state-backed newspaper.

President Xi Jinping dubbed disorder in the tutoring industry “a stubborn malady” in March, vowing to solve the problem.

The axe fell months later. “Policymakers have concluded that tutoring companies are a greater danger to social well-being than they are a contributor to economic growth,” said Ether Yin, a partner at consultancy Trivium China.

With companies feeding off parents’ anxiety while ramping up pressure on children to drive business, the social trade-off has become “unacceptable” to Beijing, he added. While the logic is rooted in reality, Hinrich Foundation research fellow Alex Capri believes the latest actions also fit the Communist Party’s reflexes to impose its will across all walks of life.

“The for-profit education sector is seen as a launchpad for students looking to gain admission to prestigious overseas universities,” Capri said. This “often promotes views which are at odds with the (Chinese Communist Party).”

It is likely that by providing state-sponsored supplemental learning services, “the party will achieve greater control of education content,” he added. The reforms also forbid providing overseas education courses.

Going underground?

The father surnamed Li, a software developer, said parents might source private tutors as teaching goes underground. “If the gaokao remains based on points, I’d hope my child can raise their scores with added training,” he added.

For now, private educators continue operating while digesting the consequences of the overhaul to the once cash-cow sector. A person with knowledge of the matter said education brand Xueersi, under the New York-listed TAL Education Group, is letting go of some teaching and sales staff.

While summer classes are ongoing, staff are uncertain if autumn or winter semesters will continue as planned. “Public listed companies will have to drastically pivot their current business model,” said Dave Wang of Nuvest Capital. “Profitability will be extremely unpredictable and uncertain.”