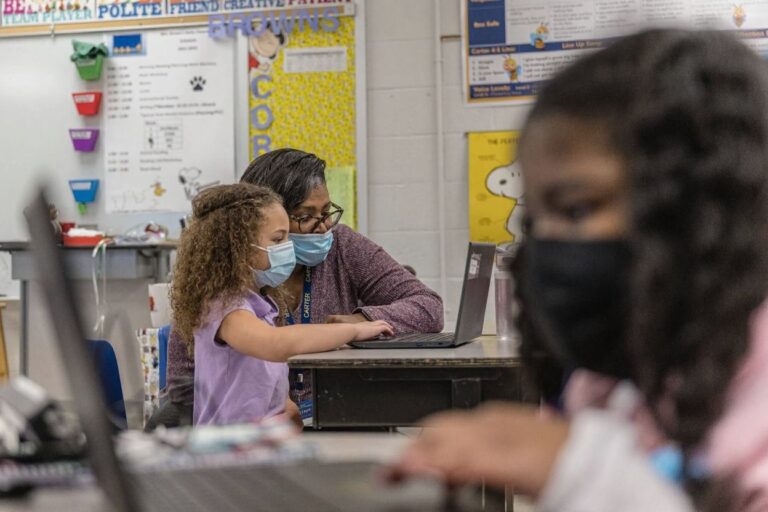

The killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, was a seismic event, a turning point that compelled many Americans to do something and do it with urgency. Many educators responded by holding mandatory workshops on institutional racism and implicit bias, reforming teaching methods and lesson plans and searching for ways to amplify undersung voices.

As a journalism professor and author of a book on race that spans more than 50 years, I’ve watched these developments with great concern. We’ve been here before, with unsettling and disturbing results.

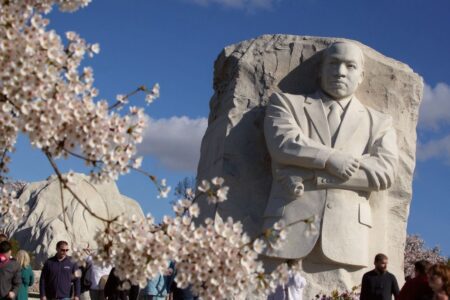

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 was also an event that spurred educators to action, motivating one teacher to try out a bold experiment touted to reduce racism.

The experiment took the nation by storm.

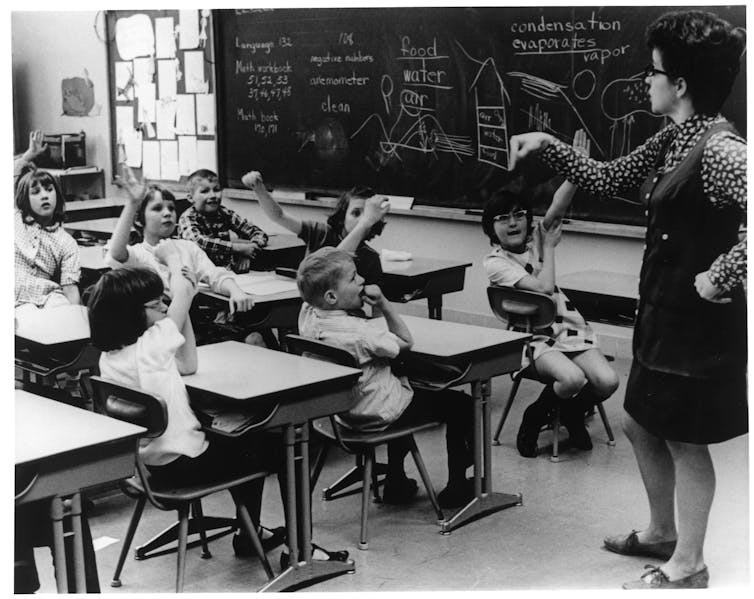

The day after King’s murder, Jane Elliott, a white third-grade teacher in rural Riceville, Iowa, sought to make her students feel the brutality of racism. Elliott separated her all-white class of students into two groups: blue-eyed children and brown-eyed children.

On the first day, the blue-eyed students were informed that they were genetically inferior to the brown-eyed students. Elliott instructed the blue-eyed kids not to play on the jungle gym or swings. They wouldn’t be allowed second helpings for lunch. They’d have to use paper cups if they drank from the water fountain.

The blue-eyed children were told not to do their homework because, even if they answered all the questions, they’d probably forget to bring the assignment back to class. That’s just the way blue-eyed kids were, Elliott told the students.

On the second day of the experiment, Elliott switched the children’s roles.

After the local newspaper published a story on Elliott and the experiment, she was flown to New York to appear on May 31, 1968, on “The Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson, where she extolled the experiment’s effectiveness in cluing in her eight-year-old white students on what it was like to be Black in America.

Charlotte Button

A darker side

But Elliott’s experiment had a more sinister impact. To most people, it seemed to suggest that racism could be reduced, even eliminated, by a one- or two-day exercise. It seemed to evince that all white people had to do to learn about racism was restrain themselves from an impulse to engage in made-up cruelty. They needed not acknowledge their privilege or reflect on it. They didn’t need to engage with a single Black person.

But in reality, I found in researching for my book “Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes” that the experiment was a sadistic exhibition of power and authority – levers controlled by Elliott. Stripping away the veneer of the experiment, what was left had nothing to do with race.

It was about cruelty and shaming.

Subsequent research designed to gauge the efficacy of Elliott’s attempt at reducing prejudice showed that many participants were shocked by the experiment, but it did nothing to address or explain the root causes of racism.

The roots of racism – and why it continues unabated in America and other nations – are complicated and gnarled. They are steeped in centuries of economic deprivation and cultural appropriation. The nonstop parade of sickening events such as the murder of George Floyd surely is not going to be abated by a quickie experiment led by a white person for the alleged benefit of other whites – as was the case with the blue-eyed, brown eyed experiment.

Sought-after diversity trainer

Nevertheless, Elliott became as famous as a teacher could become in America.

The 1970s and 1980s were ripe for diversity education in the private and public sectors, and Elliott would try out the experiment at workshops on tens of thousands of participants, not just in the U.S. and Canada, but in Europe, the Middle East and Australia. She traveled to corporations, banks, prisons, schools and military bases.

Thousands of educators across the United States folded the experiment into their curriculums. She was a standing-room-only speaker at hundreds of colleges and universities.

She appeared on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” five times.

Unsettling insults

Elliott turned into America’s mother of diversity training.

The anti-racism sessions Elliott led were intense. To get her points across, Elliott hurled insults at workshop participants, particularly those who were white and had blue eyes. For many, the experiment went horribly awry.

In doing the research for my book with scores of peoples who were participants in the experiment, I reached out to Elliott. At first, she cooperated with me. But when she discovered that I was asking pointed questions of scores of her former students, as well as others subjected to the experiment, she made an about-face and said she no longer would cooperate with me. She has since refused to answer any of my inquiries.

Charlotte Button

Scores of others did participate. I interviewed Julie Pasicznyk, who had been working for US West, a giant telecommunications company in Minneapolis. She was hesitant to enroll in Elliott’s workshop but was told that if she wanted to succeed as a manager, she’d have to attend. Pasicznyk joined 75 other employees for a training session in the company’s suburban Denver headquarters in the late 1980s.

“Right off the bat, she picked me out of the room and called me ‘Barbie,’” Pasicznyk told me. “That’s how it started, and that’s how it went all day long. She had never met me, and she accused me in front of everyone of using my sexuality to get ahead.”

“Barbie” had to have a Ken, so Elliott picked from the audience a tall, handsome man and accused him of doing the same things with his female subordinates, Pasicznyk said. Elliott went after “Ken” and “Barbie” all day long, drilling, accusing, ridiculing them, to make the point that whites make baseless judgments about Blacks all the time, Pasicznyk said.

Elliott championed the experiment as an “inoculation against racism.”

[The Conversation’s Politics + Society editors pick need-to-know stories. Sign up for Politics Weekly.]

Questioning authority

The mainstream media were complicit in advancing such a simplistic narrative. They embraced the experiment’s reductive message, as well as its promised potential, thereby keeping the implausible rationale of Elliott’s crusade alive and well for decades, however flawed and racist it really was.

Perhaps because the outcome seemed so optimistic and comforting, coverage of Elliott and the experiment’s alleged curative powers cropped up everywhere. Elliott was featured on nearly every national news show in America for decades.

Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Elliott’s bullying rejoinder to any nonbeliever was to say that however much pain a white person felt after one or two days of made-up discrimination was nothing when compared to what Blacks endure daily.

Back when she introduced the experiment to her Iowa students more than five decades ago, at least one student had the audacity to challenge Elliott’s premise, according to those who were in the classroom at the time.

When she separated the class by eye color and announced that blue-eyed children were superior, Paul Bodensteiner objected at every turn.

“It’s not true!” he challenged.

Undeterred, Elliott tried to appeal to Paul’s self-interest. “You should be happy! You have the right color eyes!”

But Paul, one of eight siblings and the son of a dairy farmer, didn’t buy Elliott’s mollification. “It’s not true and it’s not fair no matter what you say!” he responded.

I often think about Paul Bodensteiner. How can we teach kids to be more like him? Is it even possible today?![]()

Stephen G. Bloom, Professor of Journalism, University of Iowa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.