“Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history.”

These powerful words were first uttered by famed Harvard scholar Carter G. Woodson, an American historian and civil rights leader who dedicated most of his life to the field of Black Studies.

As racism continues to shape the lives of many Black people in the US, understanding Black History Month is necessary.

For Black international students, doubly so. It matters that they have all the facets of what life is like to be Black — the good, the bad and everything in between — so far away from home and in what’s exhalted around the world as the “land of the free.” It’s important that they see America clearly.

There are close to one million international students at US colleges and universities in 2021/22 — 14,438 are from Nigeria and 42,518 come from Sub-Saharan Africa.

They’re striving to become tomorrow’s doctors, innovators, lawyers, professors or scientists.

They have hopes and dreams — and a US degree can realise them. Black History Month, for all its reminders of painful histories, is also a story of exemplars — and what it takes for Black international students to join them.

Black History Month: An introduction

Woodson was focused on showcasing the efforts and struggles of Black individuals. Most of his work delved into the community’s history of slavery, years of repression and the subsequent civil rights movement. Crucially, he wished to highlight their long and arduous battle, all for the simple purpose of ensuring their equal and fair treatment.

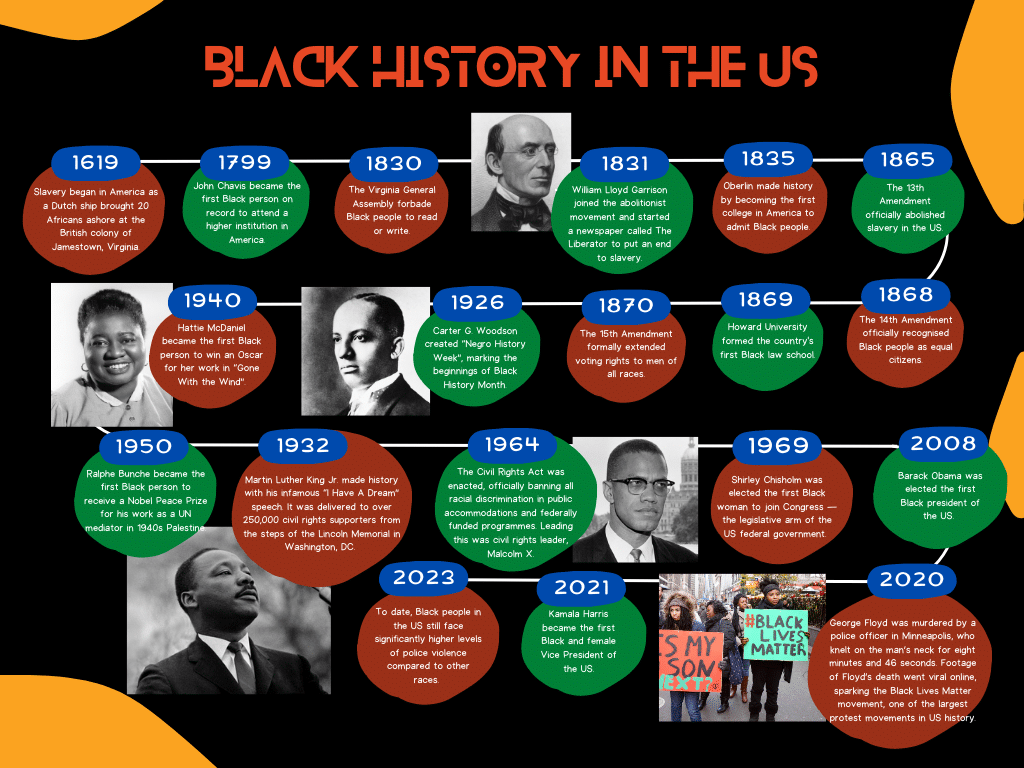

For this purpose, he created “Negro History Week” in 1926 to honour Black accomplishments and contributions to US civilisation. It’s now called “Black History Month” — and is one of the most significant events for Black people today.

Black History Month is celebrated in February every year. Whilst it initially began in the US, this month-long celebration is now recognised in the UK, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands.

Each year, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), founded by Woodson, establishes a new theme. This year, “Black Resistance,” was chosen to commemorate how African Americans have resisted oppression since their arrival upon these shores in 1619.

To be young, Black and studying in the US

Being a minority in a foreign country is difficult. Whether it is the colour of your skin or how you speak, they can affect your experience as an international student.

To better understand what it’s like to be a Black international student in the US, we reached out to two students for their experience, insights, and advice.

Hailing from Nigeria, Oluwasegun Fabiyi is currently pursuing his Master of Arts in African Studies at Indiana University Bloomington. Before this, he secured a Fulbright scholarship to study Linguistics and African-American and Diaspora Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Oluwasegun Fabiyi

Whether it’s teaching English in Northern Nigeria or studying in the US, Oluwasegun Fabiyi has found a way to adapt to different cultures, traditions, and practices. Today, the Nigerian is pursuing a Master in African Studies at Indiana University Bloomington. Source: Oluwasegun Fabiyi

Fabiyi has never experienced racism on campus. “I’d say I am really fortunate not to have people come into my face and say ‘Oh, who the hell are you’.”

Still, Fabiyi knows he is different. Most times, he is the only Black person in his class — or one of the few. Eight out of 10 of the population in Bloomington city, Indiana, is white, according to data from the US Census Bureau. While grocery shopping, the master’s student can “see the disposition of people.”

In his words, actions speak louder than voices. “You go to the grocery store and you just see people looking at you. Maybe they find you beautiful — or strange,” says Fabiyi.

Your social standing can also affect the way people treat you. In Fabiyi’s case, he is the President of Graduate Students in African Studies (GSAS). “Most of the time, I tend to represent the voices of Black people [on campus],” he says. “If anyone tries to be racist towards me, [that] is a way of trying to say you are being racist towards every other Black person.”

Click here to read the full transcript of this interview.

Hortense Minishi

Before pursuing a Master of Human Rights at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Hortense Minishi (pictured on the right) was a human rights lawyer from Kenya. Source: Hortense Minishi

Like Fabiyi, Hortense Minishi — a human rights lawyer and a single mother from Kenya — describes how lucky she was to enjoy a pleasant time while studying for a Master of Human Rights at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities (UMTC).

She had arrived in the US shortly after George Floyd’s death. “One of the things I was asking myself was: ‘Am I crazy to go to Minnesota when this has just happened?’” she says.

She was resolute that Minnesota was the right place to enhance her knowledge about human rights.

“If I am afraid, what about everyone else?” Minishi shares.

“Look back at the stories about how we fought for independence back home — how we fought for anti-slavery, the civil rights movement — it was people who had the courage and those who thought they could make a difference. I believe in making positive change.”

Minishi’s Minnesota experience is largely shaped by her campus community, a small cohort and her academic supervisor. UMTC has worked over the years to build an inclusive culture. Her cohort only consisted of 15 students — making it easy for the master’s students to develop a robust support system.

On campus, Minishi served as the Secretary for the Humphrey International Students Association. She also participated in an Equity and Inclusion Council. Her contributions in these groups were geared towards cultivating a welcoming culture at the University and a sense of belonging for all people, particularly uplifting voices of underrepresented groups including international students, Black students and women.

In 2022, UMTC’s School of Public Affairs chose Nisha Botchwey as its new dean. She is the first Black woman and immigrant to serve in that position. “That was a big deal for the school because it was the first time it happened, and it happened when I was here. So it was one of those things [that] I was super proud [of]”, enthuses Minishi.

Her friends, though, had a different experience. “I have had other friends exposed to police surveillance,” says the master’s student. “There’s always the fear that you don’t know what will happen to you or who you will meet on the street. In some instances. there are aspects of micro aggressions (even if unintended) that might occur in the ways that you are spoken as a Black person.”

Minishi (pictured on the left) with Angela Rose Myers, former President of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and a passionate Black Lives Matter activist, who has experienced first hand issues around police surveillance and discrimination. Source: Hortense Minishi

What experts have to say

It’s clear that US campuses building more inclusive and accepting communities where international students are all welcome, regardless of the colour of their skin.

Indiana University, for example, has set up a number of anti-racism measures. One is an initiative called the Racial Healing Project, which seeks to educate and inform students about historical and current manifestations of racism in the US.

At the same time, it has a White Racial Literacy Project to increase racial literacy among White students. Both work together to create a “welcoming, inclusive and equitable campus climate”.

What’s also apparent, though, is the underlying thread of otherness — as highlighted by our two interviewees. Being Black already marginalises them in the same way faced by African Americans. Then there’s the additional layer to work through: that of being a foreign student with significant differences in culture, ethnicity and language.

Despite this, there’s a sense that Black international students are not as prioritised in campus internationalisation.

For example, a Nigerian student told researchers: “For us if you go to the dining [hall] you get Asian food and everything, but no African food. No African food. So that is why I think they care more about the Asians, the Indians but …Not seeing [at] all African no, so to me that’s even indicative of the fact that they don’t care much about people from Africa.”

Herein lies a different issue entirely: there’s a lack of attention being paid to Black international students. Researchers themselves have admitted that the experiences of Black international students are “not extensively acknowledged.” More than that, there’s a sense that Black international students are commonly placed under the same broad “international” umbrella, one that ignores the cultural nuances in the category.

So, how can Black international students navigate this space? Fabiyi and Minishi have some insights to share:

“Life is about risk. We can’t say because racism is common in places, then it is evil. As a matter of fact, I think people tend to feel like because they hear [about] racism and the Black Lives Matter movement, they might think everywhere is about racism,” Fabiyi shares.

Minishi echoes similar sentiments. “I researched a lot about Minnesota, way before I came in. There’s actually a documentary about the history of Black people in the University of Minnesota called the Free North.

She adds: “I was also very aware that because of my identity, I might, in certain instances, be the only one in the room who is different, or be the only one out in the street who might receive a negative comment.”