A career in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is often considered the road less taken for women, and it’s not for lack of trying. Women in STEM face many barriers entering and staying in the field, and continue to be excluded from fully participating in the industry compared to men. Globally, only 30% of the world’s researchers are women, with less than one-third of female students choosing to study subjects like math and engineering in higher education.

While there’s still a long way to go in levelling the playing field, many women are making their own mark in the industry to ruffle the status quo. One such figure is Natalie Chapman, one of Australia’s prominent figures in STEM who has decades of experience in science and commercialisation under her belt. Her award-winning company, gemaker, aims to bridge the gap between research and industry to market brilliant innovations that improve the lives of others.

No stranger to the grit and grind required of women in a male-dominated field, Chapman is passionate about empowering women and girls to enter the STEM industry. We caught up with her in conjunction with the International Day of Women and Girls in Science to learn about her work and accomplishments:

Tell us a little bit about yourself, your background, and your current role.

My name is Natalie Chapman. I’m currently the managing director of gemaker, a science and technology commercialisation agency. I started gemaker 10 years ago after I’d spent a decade commercialising technologies and growing businesses at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO).

I have a chemistry degree, as well as a masters of marketing and MBA. For more than 20 years, I’ve helped researchers and innovative companies get their technology out of the lab and into use to help people, the planet and the industry. We cover every step of the commercialisation journey, including sourcing funding, market research, IP protection, as well as marketing and communications.

When did you first realise your passion for STEM? Did you always want to pursue a career in this industry, or was there a defining moment in your life that pulled you into science and technology?

I’ve always had a passion for STEM from when I was quite young. My stepfather was a chemist and my mother was a mathematics teacher. My stepfather had a chemistry set — not one of those child safety approved kits. It was about four times bigger, with a range of chemicals that could blow your head off! We loved doing experiments on the dining room table. My mother took my sister and I to Questacon in Canberra when it first opened, and we visited science centres frequently.

In Years 11 and 12, I did as much science as I could, studying chemistry, biology, mathematics, physics, and engineering science.

I didn’t know what I wanted to be when I went to university, but I knew I wanted to do something in science. At the end of my university studies, I decided I was best suited to helping people understand the benefits of new technologies.

Women in STEM are still very much underrepresented. From your experience, what were some of the major challenges that you faced in a male-dominated industry?

Networking and small talk. This may sound small but it’s not. Building professional relationships is important to moving up and doing business. I found that many of the men in the industries we were in were comfortable talking about sport with each other as an icebreaker and relationship builder.

Not being interested in sport has always been a struggle. I find now that I’m in my forties, my generation is also comfortable talking about their children and what they’re up to, which allows me to converse with them much easier.

“More in-school STEM traineeships and cadetships for universities specifically targeted for girls would be incredibly useful.” Source: Natalie Chapman

For women, getting a STEM degree doesn’t necessarily translate into being successful in the workforce. What are some of the changes that need to occur within the STEM industry in order to create enabling conditions for women to thrive in their careers?

Having women at board-level and senior management allows for a female perspective on things. For example, some men struggle with how to write a position description for roles in order to attract more female applicants. Often, the language used is a deterrent to women.

I think we need more male sponsors of women in the industry. Having a respected male put us forward for projects and appointments helps to level the playing field. (Yes, there’s a sporting reference there!) How many men still interview women of child-bearing age and think, “I’ll choose the male candidate because they won’t need maternity leave at some point.” I’ve been on panels where that actually came up, and I put my two cents worth in. The woman was hired on her merits.

You’re passionate about merging the research-industry gap so that scientists can better engage with industries. With many men still holding executive and board-level positions in businesses, how are women researchers affected differently than men in getting investors for their innovations?

To change this, we need more women in the pipeline and in leadership. This is finally being recognised and supported by recent government women in STEM leadership programmes. The continued support for the Superstars of STEM programme also helps women researchers with their profiles and leadership.

We also need more investment specifically targeted at female founders and entrepreneurial academics, and more training provided for women in industry engagement and commercialisation.

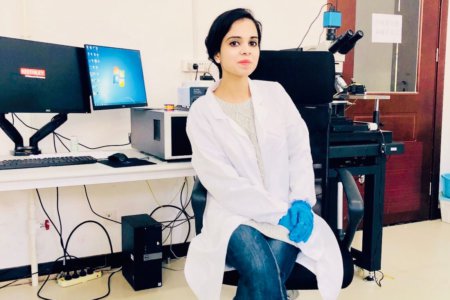

Chapman’s work at gemaker focuses on the commercialisation pathways for scientific and technological research. Source: Natalie Chapman

The team at gemaker have diverse educational and professional backgrounds. What are your thoughts on diversity (eg. nationality and educational backgrounds) in the workplace, especially in a field such as STEM?

When I started in commercialisation 20 years ago, the pathway to be a commercialisation professional was about completing a PhD in STEM and then joining a technological transfer office at a university as an associate.

Then you worked your way up, with an MBA needed for the leadership position. The rationale for this was that to help researchers commercialise, you had to have been a researcher yourself to empathise with them and have their respect.

This has been changing slowly in the last 10 years, but is still a belief held in some areas of academia. To commercialise technology you need to understand what the technology is, but not to a PhD level. You need to be able to build relationships, and you need to be able to market it, which doesn’t require an MBA either.

In 2016, gemaker conducted market research into defining what competencies were required to successfully commercialise Australian research, which requires a diverse team of people with different skills and backgrounds.

Our team at gemaker reflects that diversity and is continuously looking for more talent different to our own.

Lastly, how can STEM education be done differently at the school and university level to encourage more women into the field?

Firstly, there needs to be a bridge between STEM and Commerce subjects with innovation subjects, blending soft and hard skills together to change the world.

It’s helpful to have innovation subjects at all levels of school and university to educate students on commercialising technologies. They need to showcase more female innovators solving problems and provide the subjects as pathways to those careers.

More in-school STEM traineeships and cadetships for universities specifically targeted for girls would be incredibly useful. We need to also normalise and support parental care so that both parents can share caring responsibilities.

It’ll reassure many women to enter STEM if they know about organisations like ours, where all of us have high-impact work on incredibly important projects and getting awesome Australian innovations out to market, while working part-time or flexibly from home.