COVID-19 travel restrictions brought migration to Australia to a virtual standstill, and over the course of the pandemic about 500,000 temporary migrants have left our shores. Now many Australian businesses are screaming out for more workers.

So, who are Australia’s missing migrants, where did they work, and when might they come back?

Which migrants are missing?

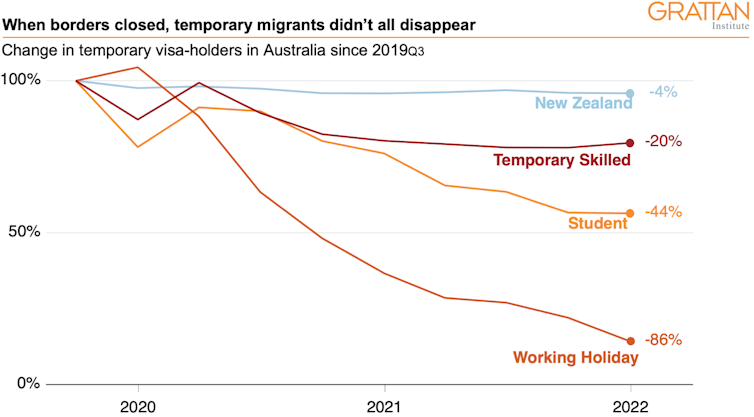

The Grattan Institute’s new report, Migrants in the workforce, shows there were about 1.5 million temporary migrants in Australia as of January 2022, compared with almost two million in 2019.

The 500,000 “missing migrants” are mainly international students and working holiday makers.

There are roughly 335,000 international students in Australia now – about half as many as in 2019 – and only 19,000 working holiday makers – about 85% fewer.

The number of temporary skilled workers is down by about 20%. Almost all of the 660,000 New Zealand citizens living in Australia on temporary visas remained throughout the pandemic.

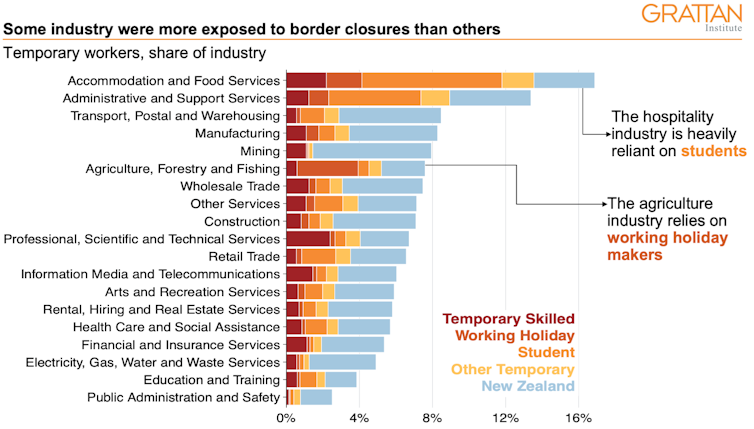

This shortfall of migrants from the uncapped temporary migration programme is hurting some businesses more than others. Before the pandemic about 17% of workers employers hospitality were here on temporary visas. These temporary migrants were overwhelmingly international students earning some money as waiters, kitchen hands and bar attendants.

Demand for these services remains high, so it’s little wonder employers in the hospitality industry are screaming out for staff. The most recent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows about 33% of hospitality businesses in February were advertising for extra staff, compared with 15% in February 2020.

Meanwhile, farmers are struggling because working holiday makers, who have made up about 4% of the agricultural workforce, are almost entirely absent.

Border closures have boosted wages where temporary migrants typically work

Some commentators, such as Australian Council of Trade Unions head Sally McManus have attributed Australia’s historically low unemployment to the border closures.

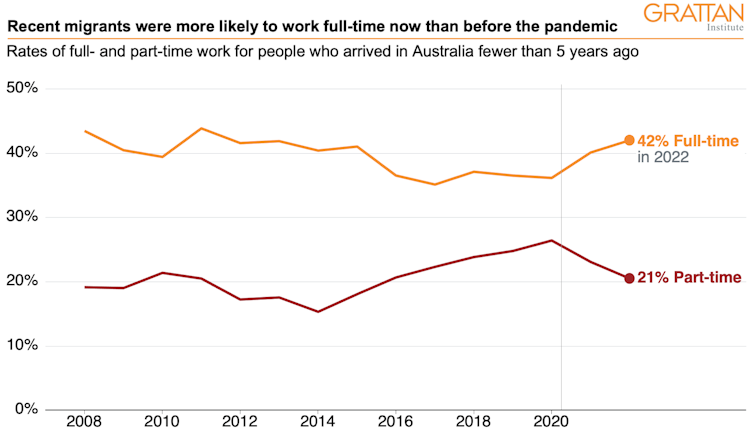

Closed borders may well have boosted the employment prospects and wages of locals in sectors where temporary migrants – especially students and working holiday makers – have made up a large share of the workforce. That’s likely to have benefited younger Australians, especially those working in hospitality.

But the fact there are fewer migrants in Australia now than before the pandemic is unlikely to have had much impact on the employment prospects and wages of Australian workers overall.

When migrants come to Australia, they spend money – on groceries, housing, transport, hospitality and so on. Fewer migrants means less of that spending, which means less demand for labour to make those goods and provide those services.

Grattan Institute research published in Febuary shows government spending and the Reserve Bank’s stimulus policies, not border closures, are the main reason for the the low unemployment rate.

Our analysis shows the effect record low interest rates and unprecedented levels of government support for businesses and households is seven to eight times larger than the effect of the border closure.

Whoever wins the federal election should resist the temptation to make permanent changes to visa policy

The federal government has implemented short-term measures to attract international students and working holiday makers back to Australia. It is refunding the application fee to those applying for such visas, and has removed the 40-hour per fortnight cap on working hours for international students.

But whichever party wins the election should avoid further changes to visa policy in response to what are short-term labour shortages.

Students and working holiday makers are likely to gradually return now that borders have reopened. Treasury expects the net overseas migration to increase from 41,000 people in 2021-22 to 180,000 in 2022-23 and 213,000 in 2023-24.

History shows expanding pathways to lower-skill, lower-wage migrants risks putting downward pressure on the wages of workers now in those roles.

As we have seen in agriculture and hospitality sectors, once an industry relies on low-wage labour, it is hard to wind the clock back.

Temporary changes to migration policy to solve short-term problems have a habit of becoming permanent.![]()

Will Mackey, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute and Brendan Coates, Program Director, Economic Policy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.