When Yee I-Van describes the Malaysian game industry, he doesn’t mince words: “Malaysia is booming currently.”

After more than a decade working in game education — including stints founding programmes, working at MDEC (the Malaysian Digital Economy Corporation, Malaysia’s government digital economy agency), and now serving as Ecosystem Manager for Games at Asia Pacific University — Yee has a front-row seat to the industry’s evolution. And the view is increasingly promising.

Game creators can make up to US$3 million

While Yee is careful to note that “not all games launch and then become successful” and “a lot of them do crash and burn,” the success stories emerging from Malaysia are substantial.

He points to TCG (Trading Card Game) Shop Simulator as a standout example. “That guy has, I believe he’s made about 15 million ringgit (around US$3,690,039 at the time of writing),” Yee estimates, based on industry calculation methods using Steam reviews. Of course, this is entirely speculation.

In any case, it’s important to note that games like these aren’t backed by massive studios — it’s often just one or two developers working on a project.

For Yee, these stories illustrate something unique about the games industry. “Most careers can give you a much clearer pathway — for example, you join accountancy, you do your exams, you get your papers, get your qualifications to slowly rise up the ranks,” he explains.

“Games, you can work for someone and rise up the ranks, but there’s also the option to be a little bit more entrepreneurial and then go for the route of making products itself.”

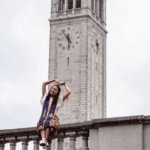

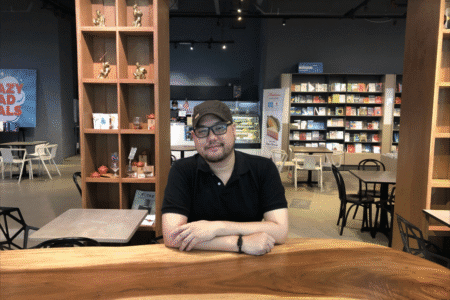

I-Van Yee is a pioneer in the Malaysian game industry and education scene. Source: I-Van Yee

Having government support for games is a rarity

One advantage Malaysia has over many countries is institutional support. It’s one of the few countries with a public agency dedicated to boosting the field.

MDEC provides funding for game startups, offering grants ranging from RM100,000 to RM2 million (US$25,387 to US$507,743 approximately) depending on the studio’s scale and growth stage.

While that’s helpful, Yee acknowledges a potential pitfall: developers becoming “grantrepreneurs.”

These are developers who produce products that don’t generate revenue, instead moving from one grant to the next, becoming dependent on government funding rather than building sustainable businesses.

Still, he believes the support is essential. “Without them, a lot of us wouldn’t even have a chance to actually attempt it,” he says.

A gathering of game developers hosted by the International Game Developers Association in Malaysia. Source: I-Van Yee

But here’s a reality check on the Malaysian game industry

Despite big wins by creators, Yee is realistic about the challenges. “Typically, most of the studios are juggling day jobs and also at night they work on something until it becomes more sustainable and then they go full into that,” he explains.

His advice is unambiguous: “I would always advise having a day job first. Don’t starve to death trying to make that indie game, because we never know how successful it will be, either negative or positively.”

Grants can help some independent studios jump straight into full-time development, but Yee counsels aspirants to hedge their bets.

The industry also demands a specific type of person. “It is also a hard industry, and it requires people who really dig in and then we have to be like super nuts,” Yee notes.

Fostering the games education and the wider ecosystem

To help make sense of Malaysia’s growing games scene, Yee runs Games HQ, a community group that tracks studios, released games, jobs, and even programmes. They maintain a website, mygamedev.info, which serves as a comprehensive resource.

Aside from that, he has also pioneered lots of the games education in Malaysia.

When tasked with designing game programmes, Yee employs a simple guiding principle: create the course he would have wanted as a student. “I would have loved to have more networking connections, more opportunities to make cool stuff, less exams,” je says.

That’s why he pushes for vocational skill set-based education. The move made MQA (Malaysia’s quality assurance agency) uncomfortable, but the team held firm, replacing exams with assessments, project work, and real-life applied knowledge.

His approach is rooted in outcome-based education. “We start from the outcomes and then we work backwards to figure out how to get to that point,” he explains.

If the goal is to produce a competent game artist, the team identifies what the industry wants, what gets graduates hired, and reverse-engineers the curriculum from there.

But one of the Malaysian game industry’s challenges is finding qualified educators. “People in my field, as we graduate, we jump straight into work and money. No one’s really thinking about taking their postgraduate,” Yee explains.

This creates a small pool of people eligible to teach at universities, which often requires master’s degrees or higher.

APU’s solution is to launch a master’s programme specifically for games. Industry experts who are interested in teaching can now get trained there, which is great as there aren’t many pathways for it in Malaysia.

Staying relevant is another ongoing issue. His solution is encouraging lecturers to work on projects, take consultancies, and maintain strong industry connections. Thankfully, the universities often also benefit from their alumni network. Graduates who are already working are often happy to share what the latest developments are in the industry.

Despite building his career in Malaysia, Yee remains a strong advocate for international education, as it widens one’s horizons.

The experience provides perspective, showing students both what their home country does well and where it can improve. His own year abroad opened his eyes while reinforcing his belief in Malaysia’s potential, particularly for aspiring entrepreneurs in the games industry.

Yee has also helped organise Global Game Jam events in Malaysia, with Global Game Jam being the world’s largest annual game creation event. Source: I-Van Yee

Is studying games worth it?

Despite being “honour-bound to say diploma education is important” as an educator, Yee is refreshingly honest about alternatives. “The truth is, most of the stuff that universities teach nowadays is available online. There’s something out there, whether it’s a Udemy or Coursera or some online programme.”

So why should anyone attend university still? Yee identifies several advantages:

First is networking. You meet not just the lecturers and mentors, but also students who one day will be your peers in the industry. Yee has seen students who attend industry events easily get internships, jobs, opportunities, and projects.

Next is mentorship. Having someone who has gone through the problem before actually helps speed up the process. His generation “did everything wrongly basically,” and that experience can help students avoid the same mistakes.

And of course, the infrastructure in universities is much better than your home studio.

Yee also believes that it’s critical to visit schools and ask questions — not of marketing staff, but of lecturers and current students.

While the marketing guy obviously has to promote the school (and downplay downsides), talking to lecturers and finding out the kind of stuff they’ve been doing and teaching might give deeper perspective.

Most importantly, talk to current students. “If students are miserable, then I would say you might want to check somewhere else,” he says.

For students entering the Malaysian game industry, Yee is clear about what employers prioritise: “Your portfolio, your attitude, and your paper.”

The certification matters — it can affect pay grade— but in a creative industry, demonstrated ability comes first.

“Your cert is actually just a license for you. It’s a key that opens more doors,” he explains.