Johns Hopkins students and faculty members are building the future at the Whiting School of Engineering. Two projects highlight recent innovative research aimed at building cleaner, more accessible energy grids and accelerating the discovery of new materials for renewable energy storage.

Johns Hopkins University is the nation’s leading academic institution in total research and development spending, according to the National Science Foundation. Source: Johns Hopkins University

Designing smarter microgrids

Whiting School student Raymond Gong used mathematical modelling to address a critical sustainable energy challenge: making clean, reliable, and affordable energy accessible to people in remote or underdeveloped areas.

Gong found that with the right policy incentives, localised energy networks known as hybrid microgrids can produce fewer carbon emissions, use more renewable energy, and cost less overall. His work offers a data-backed strategy to help underserved regions invest in cleaner, more reliable power systems.

“Smart policies can really make a difference in shifting toward cleaner energy,” Gong said. “You don’t have to give up reliability or affordability to go green.”

To identify the most cost-effective and sustainable microgrid setups, Gong developed a simulation-based model that tested different combinations of energy sources and policy incentives. His goal was to find configurations that balanced affordability, reliability, and clean energy use.

He found that with well-designed policy incentives, microgrids could significantly increase their reliance on renewables while lowering overall system costs, without sacrificing performance and reliability. Systems that paired moderate carbon reduction incentives (like a small fossil fuel tax) with strong renewable energy subsidies (like solar panel rebates) consistently outperformed others in cost and emissions.

To support those findings, he ran two advanced simulation models focused on solar and wind power: one predicted production using historical weather data, accounting for the ups and downs of natural variability, while the second used Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to model the performance of key microgrid components — such as solar panels and wind turbines — over time, factoring in wear, failure risk, and maintenance needs.

Next, Gong developed a tool that calculates total expenses, which considered financial factors like the costs needed to install a hybrid microgrid system and operating costs, among others. He also factored incentives for using renewable energy and for reducing carbon emissions.

He then applied a Mixed-Variable Simultaneous Perturbation Stochastic Algorithm (MSPSA), an optimisation technique designed for complex, unpredictable systems. He compared its performance to Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO), a method used in energy planning to find the most efficient solutions by mimicking the collective behaviour of birds or fish.

“What surprised me was how much better MSPSA performed compared to PSO — not just in speed, but also in its ability to identify cleaner and more cost-effective solutions,” he said.

For more than 100 years, Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland has been preparing engineers to rise to the challenges of a changing world. Source: Johns Hopkins University

Building better batteries

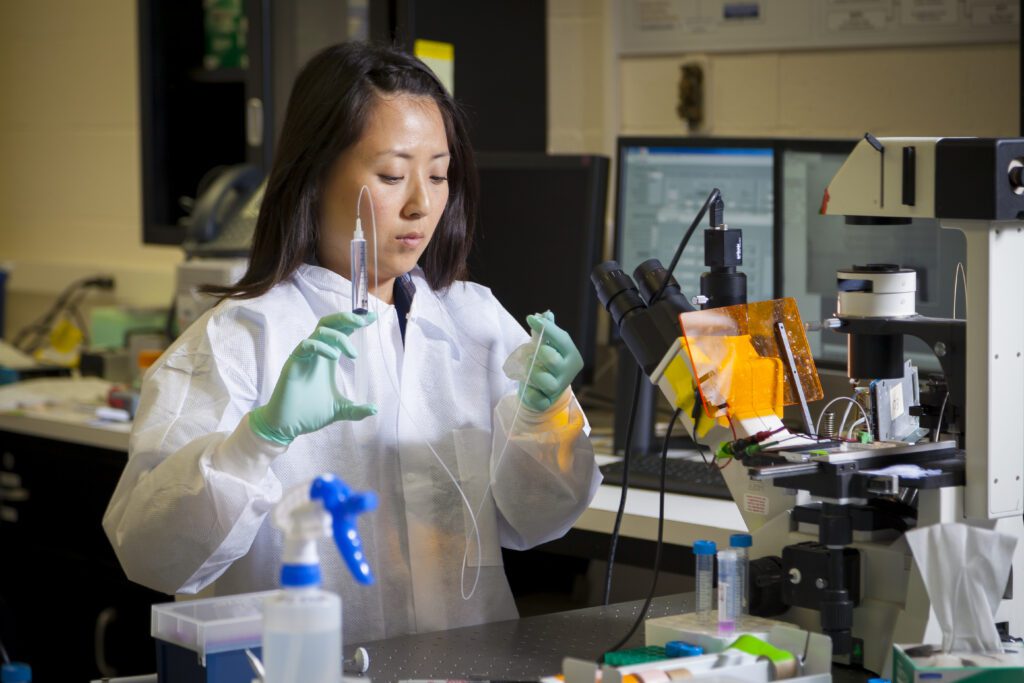

Johns Hopkins researchers, supported by the Ralph O’Connor Sustainable Energy Institute, created an automated platform that could speed up the search for better materials for renewable energy storage. The system combines electrochemistry, artificial intelligence, and robotics to rapidly test and analyse electrolytes — the liquids or gels that transport charged particles in batteries — helping scientists identify better batteries much more quickly.

Though most of the group’s work has focused on zinc metal batteries, its new approach could be applied across all types of metal batteries, said Whiting School postdoctoral fellow Dian-Zhao Lin.

“Our platform can test hundreds of formulations in days rather than months using traditional trial-and-error methods,” Lin said.

The early stages of this project focused on designing microelectrode bundles, establishing automated protocols, and validating the reliability of the system. Once the working platform was created, researchers integrated machine learning capabilities to predict zinc metal battery electrochemical performance, discover new electrolytes for high-performance batteries, and uncover property-performance correlations.

The result is an affordable and customisable high-throughput experimentation platform that dramatically accelerates electrochemical research.

“Techniques that rapidly test large numbers of samples in parallel — known as ‘high-throughput methods’ — have revolutionised fields like pharmaceutical chemistry and materials science, but their implementation in electrochemistry has been limited due to technical challenges and cost barriers,” Lin said.

He also noted the platform avoids those technical issues and uses off-the-shelf components with custom 3D-printed parts, making it more affordable.

The automation aspect of the system solves a common problem with traditional high-throughput systems — reproducing exact conditions for multiple tests at the same time.

“Because it is consistent, our new platform generates more reliable data,” Lin said. “This standardisation leads to more robust scientific conclusions and accelerates real progress rather than spending time troubleshooting inconsistent results.”

The team plans to expand their platform’s use to other areas, including fuel cells, electrolysers, and CO₂ reduction. He believes that any field relying on high-throughput experimentation can benefit.

“The possible combinations of electrolyte components are virtually infinite, and traditionally we’ve explored this space through intuition and trial-and-error,” Lin said. “By combining high-throughput experimentation with automation, we’ve created a systematic approach to navigate this vast chemical space efficiently, leading to discoveries that might otherwise have been missed.”

Follow Johns Hopkins University on X, Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube, and Instagram.