Food is everything to Malaysians. From family tables to national festivals, food is seemingly everywhere.

Except in its university curriculum.

Growing up in Penang, a state known for its legendary laksas and nasi kandar, En Min Saw discovered this gap. In 2019, when she was searching for nutrition degrees at local universities, she found few options.

So she left.

Min’s final year research project for her nutrition degree discussed how nutritionists and dietitians in Australia use social media. Source: En Min Saw

What to do when the best nutrition programmes weren’t available in Malaysia

Min’s passion for food started in her grandma’s kitchen, where she would help chop garlic and onions.

That love grew through school and later took her to the University of Leeds, where she studied food science and nutrition.

Food science focuses on the manufacturing process, for example how the food is packaged, processed and preserved.

Nutrition looks at food more directly. It breaks down what goes onto a plate and how each element contributes to health.

As Malaysia grapples with rising obesity rates, undernutrition in rural areas, and a growing interest in wellness, the need for homegrown nutritionists is greater than ever.

But without more degrees and policies to support nutrition students like Min, many have to seek knowledge and opportunities abroad.

Although COVID hit and Min had to leave Leeds, she returned home to complete the first two years of a dietetic degree at the International Medical University (IMU) before leaving once more.

“IMU had twinning programmes to Australia, so I didn’t think much into it,” she says. “I was young and still wanted to explore more.”

This time, it was to complete the rest of her programme at the University of Newcastle in New South Wales.

She’s since graduated with a Bachelor of Nutrition and Dietetics (Hons) and is now a Performance Nutrition Coach at Fueld Fwrd in Sydney and Media Dietitian for monthly magazine and website Australian Healthy Food Guide.

Australia gained another nutrition expert in Min — at the expense of Malaysia, a country many would argue is in greater need of one.

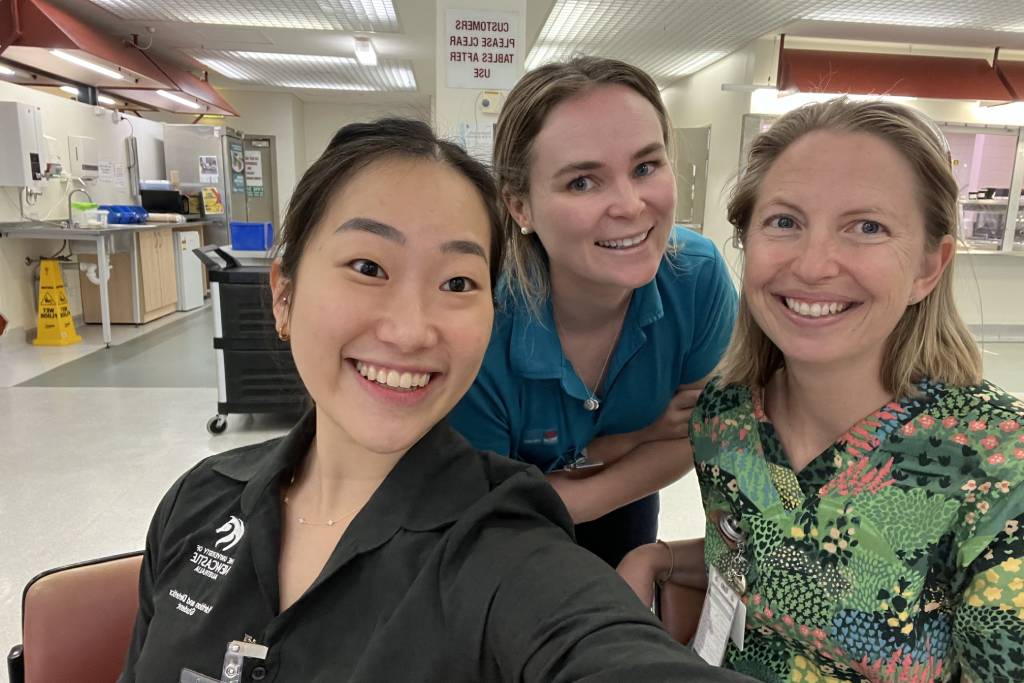

Min has worked with many professionals in nutrition, including her supervising dietitians at John Hunter Hospital. Source: En Min Saw

Heaty or healthy? A nutrition programme graduate merges Asian wisdom with science

In Australia, nutrition is already a well-established field. In Malaysia, not so much.

The National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2024: Nutrition report reveals:

- 6% of adults (aged 18 years and above) are either overweight (30.5%) or obese (23.1%)

- 59% of adults drink sugary drinks daily

- 9% of Malaysian adults consume diets high in salt

- Only 13% of adolescents and 17% of adults meet the recommended fruit intake

Compared to other Asian countries like Singapore, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, ranked the world’s healthiest, Malaysia lags behind.

Lifestyle plays a big part in that difference. Australians, for example, wake up as early as 5 am to go for a run. And sure, they enjoy food, but it doesn’t control their day-to-day routines.

In Malaysia, the relationship with food couldn’t be more different.

“Some people will tell you chee cheong fun (oily rice noodles doused in sweet and salty sauces) is their favourite breakfast, and they simply must have it,” says Min.

And with food available 24/7, it’s easy to see why late night outings to the mamak (a local fast food joint serving mostly greasy fare) are a norm.

Cultural beliefs also shape eating habits. In Chinese households, for example, older generations classify food as “heaty” or “cooling.”

“Heaty” foods like fried chicken, ginger, and durian are believed to increase body heat. Meanwhile, “cooling” foods like cucumber, watermelon, and broccoli lower body heat, which is believed to cause indigestion.

Some of these traditional beliefs don’t align with what modern nutrition teaches us.

But Min is hopeful about the future of nutrition in Malaysia, thanks to efforts to update the country’s nutritional guidelines.

Growing up, the prevailing healthy eating guideline was a food pyramid that advised for a daily intake of:

- five to seven servings of rice or other carbohydrates

- two servings of fruits and vegetables

- three servings of meat

- small amounts of fats, oils, sugar, and salt

In 2016, the Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia released the “Healthy Eating Plate” model: half the plate should be vegetables, a quarter should be carbs, and the other quarter should be protein.

“I think this is a better representation,” she explains. “When I look at the food pyramid, it doesn’t really connect with what’s actually on my plate. But the ‘Healthy Eating Plate’ model is something people can understand instantly.”

View this post on Instagram

Asian food can be as healthy as salads

There was a time when Min believed Asian food had no place in a healthy diet.

Social media was flooded with bodybuilders eating nothing but chicken breast and broccoli, and she assumed that was the only way to eat well.

“I felt like I didn’t have the qualifications to be a dietitian because my own diet didn’t follow these health principles.”

Over time, she realised that health isn’t about strictly adhering to a “gold standard” of food. It’s about making adjustments that suit your lifestyle because health is also about your mental and cultural well-being.

“I love Wan Tan Mee,” she admits. “If I cut it out of my diet just because I think it’s too carb heavy, I’d be really sad. It’s been a part of my life forever.”

So, instead of eliminating it, she focuses on finding ways to keep the dish in her life while making it more balanced and healthier.

Having seen first-hand the lack of science surrounding food among Malaysians, Min knows how easy it is believe myths and even feel like it’s impossible to be Asian and to be healthy.

She currently runs @good.food.gang, where she posts content answering today’s top fitness and wellness questions like how to not feel sore after workouts, how to find high-protein snacks that don’t suck, and how you can still eat your favourite processed food without feeling guilty.

“At first, I was sharing aesthetic café-style creations,” she recalls. “But when I moved to Australia, I didn’t have the time to prepare such elaborate meals.”

That’s when she shifted to making quick, nutritious dishes while pairing them with easy nutrition facts, and her audience loved it.

“That motivated me to keep going,” she says. “I know how challenging it can be — I struggled with my diet when I was younger. Now, I want to be the guide I wish I had back then.”

Below she helps us debunk five nutrition myths in Asian households, so we can still enjoy our food and stay healthy at the same time.

As a volunteer at a community centre, Min helped to raise awareness about good nutrition, even at events like an Aboriginal opening ceremony. Source: En Min Saw

A nutrition graduate debunks 5 common food myths

1. Salads are better

Many students think eating healthy abroad means giving up their cultural foods. Min doesn’t see it that way.

“At home, they eat rice with their meals, but once overseas, they switch to salads because they believe it’s healthier. The truth is, you don’t need to abandon your culture to eat well,” she says.

She recommends making small changes instead. This could mean having smaller portions of rice, cooking more vegetables, prioritising protein, or replacing heavy sauces with lighter, spice-based alternatives.

2. Getting takeout is unhealthy

Eating out every day while studying abroad might feel easy, but it can drain your wallet. Plus, healthy options generally cost more.

But Min believes takeout isn’t the enemy. “I’ve been there,” she says. “When you’re buried in work, cooking is the last thing you want to do.”

Her trick is to pair takeout with something from home. For example, if she gets a large portion of butter chicken, she’ll add some broccoli and portion it out to make sure she’s not overeating one thing.

3. Overnight meals are not good

The microwave might be a kitchen essential for many, but at one point, many believed that microwaving food causes cancer.

But when you’re living alone abroad, preparing fresh meals every day just isn’t practical.

“Microwaves don’t cause cancer,” Min explains. “If using one helps you stay on track with your health goals, there’s no reason to worry.”

Ready-made meals make it easier to meet daily carb, protein, and fibre requirements, keeping energy levels steady and productivity high.

The microwave simply makes it more convenient to access that nutrition.

4. Frozen vegetables are filled with preservatives

Another common misconception is that frozen vegetables are processed and filled with preservatives.

But in reality, they can be just as nutritious as fresh vegetables — if not more so.

In Australia, vegetables are flash-frozen immediately after harvest. “The farmers use flash-freezing equipment, and the factories are close to the farms,” Min explains. “Once the produce is picked, it’s immediately sent to the factory and frozen.”

This process locks in nutrients at their peak without the need for preservatives, preserving their nutritional value.

“And when you don’t have time to shop, frozen vegetables are a lifesaver,” she adds. “Frozen corn, for example, is perfect to toss into fried rice.”

5. Rice makes you fat

If you’ve ever been around Asian “aunties,” you’ve probably heard this: “I’m not eating rice anymore, I’m on a diet!”

This is because they believe that fewer carbs equal weight loss. And while it may seem effective at first, Min explains why this is misleading.

“Yes, they will lose weight,” she says, “but that’s because carbs bind with water. For every gram of carbs, you’re losing four grams of water.”

This means that when you cut carbs, you’re actually losing water weight. As soon as you bring rice back into your diet, that weight will right back.

The problem is that rice is deeply rooted in Asian food culture. You can’t just cut it out.

Min believes the smarter way is balance. Instead of going for extreme changes, she suggests adopting a more balanced mindset. The key is asking: Is this something I can keep doing?

From there, it becomes easier to find healthier, more realistic options that are actually sustainable over time.