Architecture delivers social progress. We see this in Victorian era hospitals, grand civic centres of the early 20th century, post-War temples of the welfare state, and the shiny skylines of 21st century cities.

Architecture is far from being a mere service industry for the creation of buildings. In reality, buildings accommodate all of urban society’s vital functions and are instruments of change. They usher in the urban future, harbouring bold and sensitive design that shapes a more inclusive, equitable, beautiful and sustainable world. The architect has a powerful yet subtle ethical role.

Never has the clarion call for architects to embrace a social agenda in their work been more urgent than today. Data on our unique urban condition confirms this.

About 70 percent of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas by 2050. Nearly a quarter of the world’s population (except Africa) will be ageing societies by then, according to United Nations data. The Climate Change Clock estimates we only have until 2045 before the devastating effects of global warming become irreversible. For tomorrow’s architects, putting people and the environment first is more essential than ever.

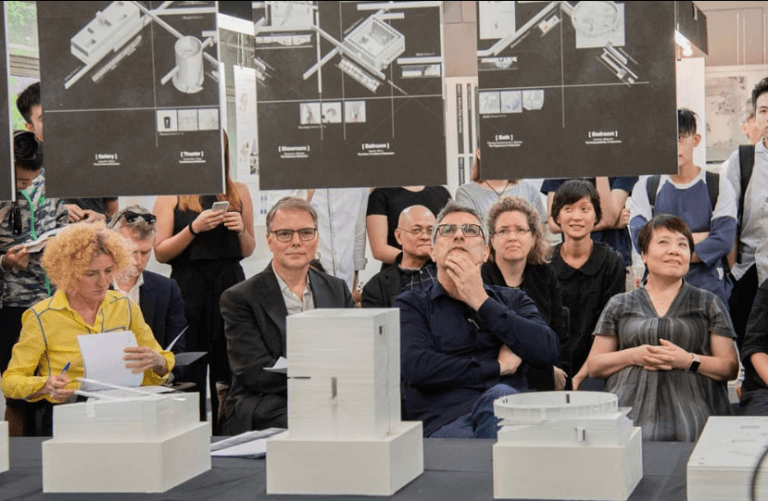

Source: University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Architecture

The Faculty of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) is located at the epicentre of high-density, ultra-rapid urbanism. Here, commitment to innovation and sustainability empowers forward-looking architects and other urban professionals currently shaping this innovative region. As Dean Chris Webster explains, the faculty is “at the forefront of tackling some of civilization’s most pressing resource allocation problems, including shaping living-working habitats for centuries to come.”

To this end, HKU takes an approach to education unlike any other architecture school.

With the world’s leading urban social scientists, architectural historians, urban theorists and sustainability scientists at its helm, education here is never a static, rigid process.

Rather, educators maintain a unique blend of subjects and methodologies that are both cutting-edge and relevant, never missing out the very best of scientific, arts and humanities scholarly tradition.

Such progressive strategy is crucial. As Associate Professor Juan Du writes, the practice and discourse of architecture will fundamentally differ from the past – a time that gave rise to unsustainable trends in urbanisation.

Source: University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Architecture

“The importance of understanding the city is more pertinent today than ever before,” writes Du.

And Hong Kong presents the perfect base for teachers, researchers and students to discover how future cities must be configured.

“HKU recognizes the complex and rapidly changing city of Hong Kong as an authoritative site of learning, providing a living classroom for the research of urbanisms, both past and emerging,” says Du.

Knowledge alone isn’t enough. HKU knows the architects of tomorrow need an ethical foundation to build on; a moral backbone from which the application of undergraduate, masters and doctoral education across built environment subjects can realise a better and more inclusive world for all.

There’s no single ideal urban future. Will city centres continue to be dominated by commerce? Will private government or residential neighbourhoods replace the public government model of the 20th century? Will cities continue to grow inexorably, breaking the 10, 20, 30 and 40 million population barriers?

Source: University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Architecture

There are daunting technical, design and ethical dilemmas ahead for those working in built environment professions. HKU’s approach to facing them teaches students to be conversant across multiple disciplines; to access the best scientific and philosophical ideas to analyse urban problems.

This starts with something as simple as encouraging a wide range of experimentation with functional, environmental and social challenges in undergraduates’ design studio sessions. Opportunities to join an International Student Exchange Program promise the chance to benefit from broader perspectives and experiences. All undergraduate architecture and landscape students spend a semester in HKU’s very own Shanghai Study Centre.

This is also driven by HKU’s investment in five new specialist labs, filled with state-of-the-art technology specifically-designed to tackle the top challenges the profession faces today (Sustainable High Density Cities; Healthy High Density Cities; Smart High Density Cities; 5D-Building Information Modelling Lab; Architectural Conservation Lab).

Then there’s HKU’s simple but effective way of teaching sustainability. Yes, it covers the big picture, holds the debates and reads the alarming science. But it also teaches skills for making a difference on the ground, offering Environmental Technology modules that give design students exposure to state-of-the-art models and visualisation software for future-proofing buildings and urban design for energy, thermal comfort, carbon footprints, building and occupant health, and more.

Source: University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Architecture

As Assistant Professor, Chad McKee explains: “What does it mean for a building to be environmentally sustainable? How do we measure, analyze and understand the environmental performance of buildings? What can we learn from well-tested indigenous ‘vernacular’ knowledge of climate and construction? And how should we combine this knowledge with contemporary technology to create new potentials for architecture that are good for both people and the environment?”

“These questions underpin the design research agenda and teaching pedagogy for the environmental technology curriculum at The University of Hong Kong,” he adds.

With innovative teaching, progressive research and a clear commitment to people-oriented environmental ethics, HKU is building a brighter future.

Follow the HKU Faculty of Architecture on Facebook and Vimeo

Liked this? Then you’ll love these…

Create the future of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong

HKU: At the intersection of architecture, education and urban living