Growing up, Mamunur Rahman saw how his sisters were denied school, toilets and sanitary pads. Their home was Dhaka, Bangladesh, stricken by poverty and where misogyny runs deep.

Although more girls are in school now, two out of three women report experiencing some form of partner violence. Rahman saw first-hand how his mother and sisters were discriminated against in family life and in society.

At the University of Sussex, under a Chevening Scholarship, he found out why. “I found out why my sisters could not pass their middle schools because there weren’t toilets to manage their menstrual hygiene,” he says. “My sister didn’t have access to sanitary napkins and because of this girls are dropping out of school every year — up to 41% in my country.”

He vowed for his nieces to never have to go through the same. His initiative ELLA Pad, run by poor working women, makes low-cost sanitary napkins made of garment waste. “About four million women work in 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh. Most factories have inadequate toilets and many women have menstrual hygiene problems, even losing days at work because of this,” Rahman told The Guardian.

“I realised that the garment factories were throwing away so many textile scraps, and that these could be used to make eco-friendly sanitary towels. We persuaded the factories to let a group of women make their own towels, the Ella Pad, to improve health, and reduce waste.”

Rahman saw first-hand how his mother and sisters were discriminated against in family life and in society. Source: Mamunur Rahman

The cost? Almost zero but the innovation is priceless. After his Chevening Scholarship, Rahman would go on to win two more scholarships — to Hungary’s Central European University and to the US’s University of Montana and Michigan State University — for his social entrepreneurship.

We caught up with Rahman to learn more about he won all those scholarships, ELLA Pad and his future plans:

What spurred your passion for social sciences and in particular women’s studies?

My personal background. I grew up in an extremely poverty-ridden community. I saw the struggles of my mother and sisters for our livelihoods.

At my primary and secondary schools (I was in a religious school), I grew up with underprivileged students including many orphans. In fact, by default I was already in social sciences.

At tertiary level, I was selected for economics and was also a top student in science at the best uni in my country. While the teacher from economics class was narrating the GDP and GNP, I noticed women’s contributions were not calculated in the traditional economy.

This was touchy for me. It reminded me of my childhood memory of how my mother and sisters’ contribution in the family and agriculture were not recognised by society. I did my dissertation on this then proceeded to do my master’s in gender and development.

I was very interested in the subject and encountered a lot of problems during the course. During my master’s at the University of Sussex, I was oriented on how developing country issues were connected with access to toilets.

His initiative ELLA Pad, run by poor working women, makes low-cost sanitary napkins made of garment waste. “About four million women work in 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh. Source: Mamunur Rahman

I found out why my sisters could not pass their middle schools because there weren’t toilets to manage their menstrual hygiene. My sister didn’t have access to sanitary napkins and because of this girls are dropping out of school every year — up to 41% in my country.

I felt like I needed to concentrate to solve these problems so at least the daughters of my sisters don’t need to go through the same.

Walk us through your social sciences studies abroad and your scholarships.

I had the opportunity to study at world-leading unis but the Chevening Scholarship opened the doors to the international world for me. Before this programme, I didn’t even have a passport.

I did my first international degree at the University of Sussex in the UK then came back to Bangladesh. Within three months, I got an invitation from the United Nations and USAID to give a talk with UN officials and the Kabul University faculty.

I became the University of Sussex alumni coordinator and the following year I was invited to give a talk to the students. Since then, I just kept on getting connected to all the right people.

“Most factories have inadequate toilets and many women have menstrual hygiene problems, even losing days at work because of this,” Rahman told The Guardian. Source: Munir Uz zaman/AFP

The people from the Chevening Scholarship programme insisted I pursue my own project so I designed the women empowerment one and kept sharing it at different forums. The University of Bern invited me to an international conference to share my concept.

In addition to gender and development, I was interested in green economy-related courses. I got scholarships from UNIDO and UNITAR to do a certificate course from the Central European University in Hungary.

This gave me further confidence to redesign my project with a green concept. Then during the Fulbright/Humphrey selection process, I shared my project and was selected for the fellowship which is a flagship programme of the US State Department.

I was then connected with leading US institutes related to my work. I did two semesters at the University of Montana, then moved to Michigan State University for three more semesters.

I also got the opportunity to work with MIT as a research affiliate. During my time there, I shared my idea with Harvard University and Boston University. This led me to be invited by OECD to the Green Growth Knowledge Platform in Paris. I’ve also been able to share my experience of working with underprivileged women in South Korea, the Philippines and India.

Do you feel your life has changed now?

My career took a u-turn since my international degree. I was widely connected with international communities.

This boosted my confidence and gave me the courage to jump even further. Alumni across the world support each other and the Chevening Scholarship was the launching pad for my international career. This paved the way for more opportunities.

Ironically, the organisation that earlier refused to give me a job is now approaching me to work together as partners. All of these have happened since developing my own project. My international education has greatly impacted my life.

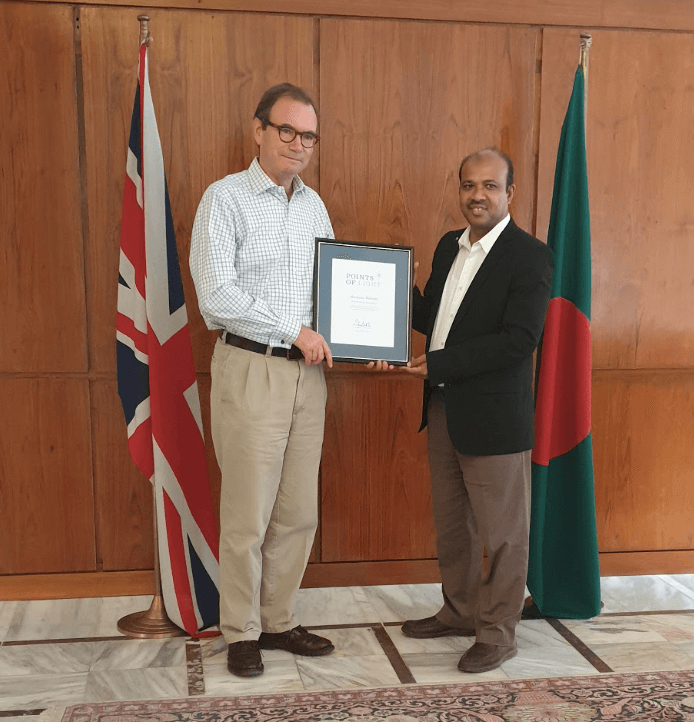

Walk us through winning the British Council’s Entrepreneurial Award for your innovation with sanitary pads.

My work was recognised by high-profile people. Winning this award widened my connections with UK policy makers including a number of British MPs.

Although it has been easy to work in my country, it also encouraged me to be more devoted. People now consider ELLA Pad as an important organisation. The team and I are inspired to expand our work at a wider level from national to international.

How do you use the knowledge and skills from uni now?

My uni courses strengthened my theoretical understanding of my current work. The idea basically came during my time at uni and getting familiar with many other practices across the world. It’s been easy to push my project further now.

What skills or knowledge do you wish you had learned more during uni?

I wish I used my time more effectively. Such as spending time networking, participating more in entrepreneurship development programmes and innovation centres. I wish I devoted myself to gaining more knowledge and spending time with the local community to get involved with social activities to expand my network.

Where do you envision yourself in 10 years?

I want to live with my own community physically but serve globally. I want to scale up the ELLA green entrepreneurship development programme.

This will not only continue the supply of biodegradable sanitary napkins but also provide a complete solution to period poverty. I intend to consider digitalisation and climate change issues as well. In the coming 10 years, we’ll focus more on policy issues to get involved in national and international policies and programmes.

What did you miss from home and how did you replace it?

I missed local foods (like rice and lentils) initially but once I discovered pasta and tuna, I got very used to this healthy and affordable substitute. I still enjoy this now.

What would you do with US$1 million?

If I was given this amount, I would use it to transform the lives of my community. This community struggles to live decent lives like not having menstrual hygiene materials.