For university students in Australia living out of reach of a campus and studying online, the growing presence of Regional University Centres is proving to be a lifeline in times of COVID-19. An early evaluation shows these centres in regional and remote Australia are highly effective in supporting students who have been historically under-represented at university and are at high risk of not completing courses. As one student said:

“I probably would not have persisted with the course if I had not seen [their centre’s learning skills adviser] to help me.”

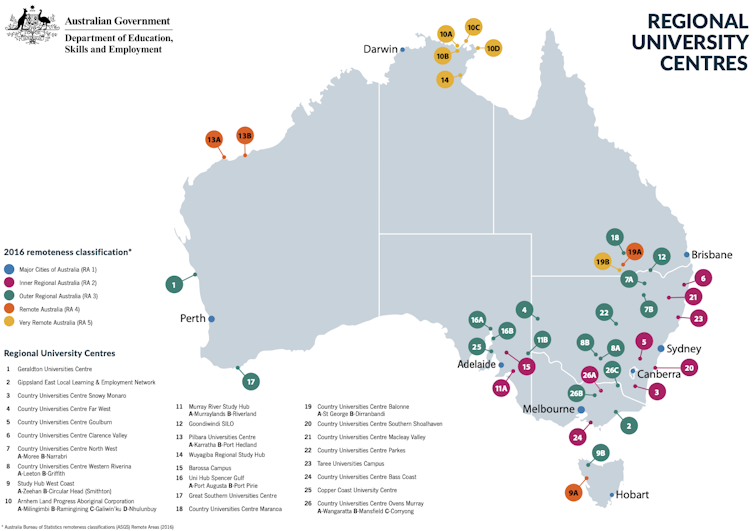

Managed locally by indepedent, not-for-profit boards formed from community members, the number of centres has grown to 26 around the country. These centres collaborate with universities to offer face-to-face learning communities for students in regional and remote areas. Within each centre are quiet study spaces, computers, internet, study support and the company of peers.

Why are these centres needed?

People in regional and remote Australia are about half as likely as those living in major cities to have a university qualification. This educational divide starts early, with high school students from these areas being about 30% less likely on average to complete year 12 than their city-based peers.

Yet research indicates this is not because these young people don’t want to go to university. Both the cost and the physical and emotional disruption of leaving home are the key barriers for students and their families.

The pandemic has led to a greater appreciation and expansion of online learning. It has given more regional and remote students of all ages the flexibility to stay and study within their local communities. Studying regionally is also more likely to lead to regional work, which boosts the local economy.

The shift to online learning has thrust the challenges of online study into the spotlight. Until recently only a minority experienced these challenges. Now there is more awareness of the need to improve support for online students, including those outside major cities.

The challenges of online learning include technology and internet connectivity problems, which are more likely in regional and remote Australia. Isolation from teachers and other students can be another barrier.

Regional University Centres are helping students in Australia to overcome these challenges. At each of the centres, they can study, link up with other students, have access to high-speed internet and information technology and get help with their study skills. Of the 26 centres across Australia, 13 are operating within the Country Universities Centre (CUC) network. A student at one these centres said:

“I have unreliable internet as I live 20km from town. Having access to CUC has helped so much. I am more motivated to continue with my studies because I love going there.”

Regional University Centres are reaching groups of students who have been under-represented in higher education. Source: Saeed Khan/AFP

Early evaluations show centres are effective

The number of Regional University Centres has steadily increased around the country since 2018. This growth has been fuelled by community willpower and funded by a combination of governments and local industry. Early evidence from CUC evaluations is starting to show the positive impact on students.

One example is the Learning Skills Advisor (LSA) program begun in 2020 to provide generic academic skills sessions across the CUC network. The first in-house evaluation provides an interesting snapshot of the students who came to LSA sessions from March 2020 to July 2021, and of the impact of the program in general.

Students from government equity categories were strongly represented. They included students from low socioeconomic status (SES) (72%) and Indigenous (9%) backgrounds. As well, 53% were the first in their families to be at university, 65.5% were aged 25 and over, and 46% were studying part-time.

Other research tells us that part-time, mature-age, low-SES, Indigenous and online students have been historically under-represented at university. If they do manage to get to university, they are more likely to withdraw without qualification. The recent snapshot tells us the centres are reaching the students most at risk.

Students wait for their turn to receive their first dose of the Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine in Sydney on August 9, 2021. Source: Dean Lewins/Pool/AFP

Students in Australia have positive feedback

The positive impacts of the LSA program are clear. The evaluation found:

- 93% of participating students reported feeling more confident about their studies

- 96% were more motivated

- 97.5% achieved higher grades

- 95% were more likely to continue with their studies.

Students in Australia said they found the practical information helpful.

“I learned about different ways to look up information. There were ideas about how to arrange information and structure essays more efficiently.”

“I learned to reference as I go, add the reference to my bibliography as I found the source.”

As students’ confidence improved, so did their grades and their motivation to continue. Their responses make this clear:

“Managed a HD/D average. I attribute this to the support I have received from [LSA].”

“Gave me the edge on exam day.”

“My confidence is up and my marks are following suit.”

Students in Australia also valued having a space to study, with the facilities they need:

“Perfect study space, away from distractions and everything that is needed right in the one place.”

These preliminary evaluation findings are highly encouraging. They show that the right type of locally available support can encourage and motivate regional and remote students. Building their confidence and skills helps them to persist and succeed.

A more formal evaluation of the CUC student experience is under way. The results are due to be published in early 2022.

The early results indicate that Regional University Centres are successfully complementing the online education universities are providing. The physical space, technology and face-to-face support the centres offer are making a difference. This is a win-win, not only for students and universities, but also for the economic, social and educational capital of regional, rural and remote communities.

The author acknowledges the help of Monica Davis, CEO, and Chris Ronan, Equity & Engagement Director, of the Country Universities Centre in the writing of this article.![]()

Cathy Stone, Conjoint Associate Professor, School of Humanities & Social Science, University of Newcastle