The eastern Indian state of Bihar is one of India’s poorest.

A person here earns 69,321 Indian rupees (US$ 790.56) in a year or 5,776.75 rupees (US$65.88) monthly.

PhD in Anthropology candidate Nikhit Agrawal was born and raised in one of its villages, Trivenigani.

On paper, it looked like he’d follow the obvious path: a degree in agriculture, perhaps?

Agrawal’s dissertation-based book project is tentatively titled “Speculating sustainability: Start-Ups and the ethnographic life of climate futures.” Source: Nikhit Agrawal

Instead, like many bright students in India, he followed the route into computer science.

“In India, good grades usually mean engineering or medicine,” Agrawal explains. “I had the grades, so I studied computer science at IIT Delhi, one of the top engineering institutes in the country.”

But everything changed when he stumbled into a humanities and social sciences class.

“The Indian legislation allowed us to take electives outside of engineering,” he says. “I took a class in Indian agriculture and was shocked by how much I didn’t know, especially about the lives of rural communities.”

Agrawal has had his research published in the Economic Anthropology, Economic & Political Weekly, Scroll.in, Wire.in, The Indian Express, and India in Transition. Source: Nikhit Agrawal

Inspired, Agrawal went on to pursue a Master’s in Sociology at the University of Delhi, a sharp turn from coding and algorithms. But far from abandoning his technical background, he found a unique intersection: how technology affects the people it claims to serve.

“Techies are often focused on building the next big thing. But few stop to ask how these innovations impact real people, especially in rural areas,” he shares.

Determined to explore this further, Agrawal made the leap to the US in 2019 to begin a PhD in Sociocultural Anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

Agrawal spent 18 months on ethnographic fieldwork for his PhD in Sociocultural Anthropology, across two agtech start-ups, rural farms, industry events, and bureaucratic workshops. Source: Nikhit Agrawal

Sociocultural anthropology: What farmers have in common with start-ups

India now has more than 159,000 recognised tech startups, according to the Press Information Bureau of Delhi.

Start-ups are promising “climate-smart” solutions to farming – often backed by venture capitalists and government initiatives. Some have produced impressive results.

For example, a pilot project by the Baramati Agriculture Development Trust resulted in a 40% increase in crop yield, a 30% reduction in chemical usage, and a 40% decrease in water usage.

Other initiatives don’t do so well.

“I wrote a paper on a start-up that promised to eliminate field burning through a microbial product,” Agrawal says. “In year one, they claimed success. In year two, it failed, and the leadership team switched jobs.”

Field burning, common in rice cultivation, is a major source of air pollution. The start-up’s product was supposed to help decompose leftover crop residue, reducing the need to burn fields. But when the product failed, farmers were left high and dry, some facing huge financial losses.

There was no apology. No accountability.

“Yes, burning was prevented. But at what cost?” Agrawal asks. “We can’t ignore the power imbalance here.”

Agrawal also serves as a contributing editor for the Society of Cultural Anthropology, American Anthropological Association. Source: Nikhit Agrawal

This is precisely what his PhD in Sociocultural Anthropology aims to unpack.

Since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, agriculture has become a hot topic in environmental policy. As governments push to reduce emissions, rural farmers are increasingly in the spotlight — and in the crosshairs of Silicon Valley-style innovation.

Agrawal is investigating the big questions:

- Who are the people behind these agri-tech start-ups?

- What promises are they making?

- How are those promises turning into digital infrastructure?

- How are they actually being implemented – and at what cost to rural communities?

“Start-ups are fashionable,” he says. “Policymakers love them because they create jobs. But what happens when a start-up, backed by powerful investors, walks into a poor village and asks farmers to give up their carbon credits? That’s a very different kind of story.”

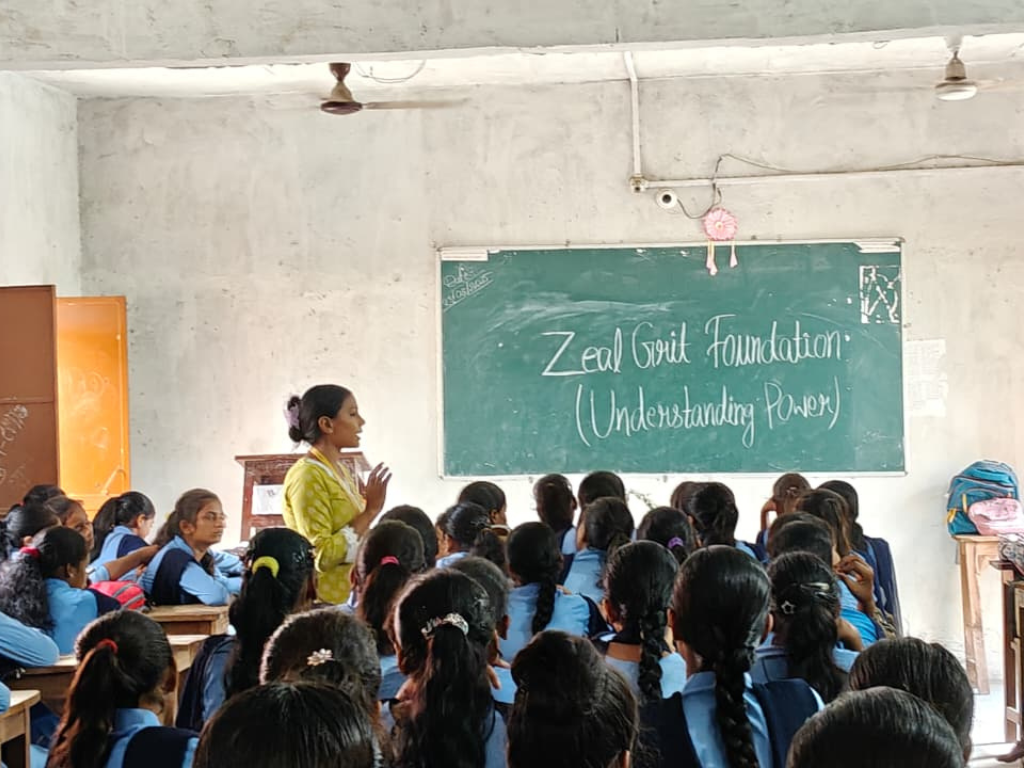

Agrawal co-founded ZealGrit Foundation, a nonprofit in rural Bihar, India. Source: Nikhit Agrawal

ZealGrit Foundation: Breaking the cycle of poor health and empowering young women in rural Bihar, India

Now in the final year of his PhD, Agrawal is back in Bihar.

He’s splitting his time between writing his thesis and working on something even closer to his heart: the ZealGrit Foundation — an initiative he co-founded to tackle the critical health challenges faced by young women in his home village.

Look out his window and you’ll see the open skies of rural India – beautiful, yes, but also misleading. Below that calm surface lies poverty, and a shocking lack of basic infrastructure.

“We don’t even have a functioning hospital,” he says. “I travel 200 kilometres for treatment. Most people here can’t afford to do that.”

ZealGrit Foundation’s session with female students about understanding power. Source: Nikhit Agrawal

That realisation sparked a question: How can we reduce the number of health cases in the first place?

Agrawal and his partner launched ZealGrit with a goal: to break the cycle of poor health through education and empowerment, starting with the most neglected group — young women.

The foundation works with schools and government-run Anganwadi Centres to run health awareness sessions focused on menstrual hygiene, UTIs, PCOS, and nutrition.

“We train girls and women how to take care of themselves, starting from puberty, through pregnancy, and into motherhood,” says Agrawal. “We’re trying to give them the tools their mothers and grandmothers never had.”