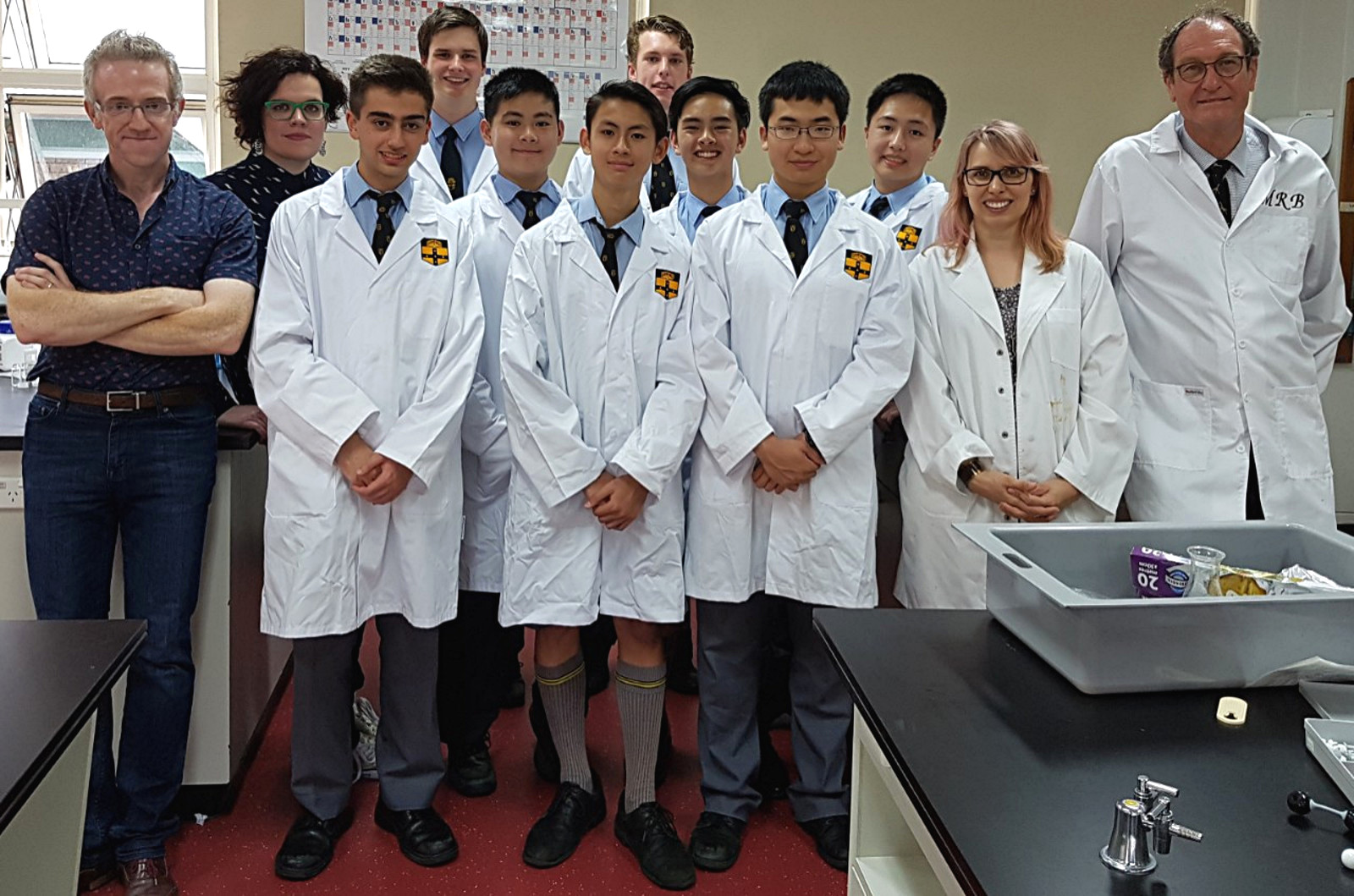

A team of high schoolers in Australia have managed to reproduce Daraprim, a life-saving anti-parasitic drug, for a mere fraction of its US$750 sticker price.

In a bid to highlight the drug’s inflated cost, the Sydney Grammar students, aged 16 to 17, were able to synthesize 3.7 grams of the drug, also known as pyrimethamine, in their school laboratory for just US$20, amounting to around US$2 per pill, while the same quantity would cost up to US$110,000 in the U.S.

One of the students, James Wood, told the BBC: “It seems totally unjustified and ethically wrong. It’s a life-saving drug and so many people can’t afford it.”

Another student, Charles Jameson, commented: “It wasn’t terribly hard [to synthesize the drug], but that’s really the point, I think, because we’re high school students.”

Martin Shkreli: Australian boys recreate life-saving drug https://t.co/TekCG1gK9Y

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) December 1, 2016

Last year, pharmaceutical company Turing Pharmaceuticals made headlines around the world when it acquired the exclusive rights to Daraprim and hiked its price up by over 5,000 percent overnight.

The drug – used to treat a common parasitic disease called toxoplasmosis in people with compromised immune systems, such as those with HIV – had originally cost US$13.50, but after the price hike, it went up to US$750.

In other countries, such as the UK and Australia, the drug retails for less than $1.50 per pill.

Martin Shkreli, the company’s CEO at the time, was widely criticized for the move, with the media dubbing him “Pharma Bro”.

Shkreli defended the price hike, saying that the drug was highly specialized and cited the need to fund further research into toxoplasmosis, but eventually decided to halve the initial price hike for hospitals, bringing it down to US$375 per 25mg pill.

In response to the news of the students’ achievement, Shkreli posted a video statement congratulating them.

In the video, he said: “We should congratulate these students for their interest in chemistry and all be excited about what is to come in the STEM-focused 21st century.”

He added that he was an “enterprising young scientist student” not long ago, and was “delighted to hear about more and more students entering the STEM field”.

However, on Twitter, Shkreli sounded less than impressed, saying “learning synthesis isn’t innovation” and that “anyone can make any drug, it is pretty easy”.

@Scottyt2Hottie uh learning synthesis isn’t innovation

— Martin Shkreli (@MartinShkreli) December 1, 2016

@Scottyt2Hottie yea uh anyone can make any drug it is pretty ez

— Martin Shkreli (@MartinShkreli) December 1, 2016

When a tweet reporting the story asked whether the students would be competition to him, he replied with a simple “no”.

@TwitterMoments ….no

— Martin Shkreli (@MartinShkreli) December 1, 2016

He also tweeted: “Labor and equipment costs? Didn’t know you could get physical chemists to work for free? I should use high school kids to make my medicines!”

Labor and equipment costs? Didn’t know you could get physical chemists to work for free? I should use high school kids to make my medicines!

— Martin Shkreli (@MartinShkreli) December 1, 2016

Hitting back at Shkreli’s comments, one of the students, Leonard Milan, told Guardian Australia: “If you follow his overpriced method using toxic chemicals in an industrial lab, it’s easy, but the fact that we were able to substitute some really toxic gasses with simple school-available chemicals and do it so cheaply demonstrates the absurdity of some of his justifications for the price.”

Speaking to the BBC, Dr Alice Williamson, a University of Sydney research chemist who supported the students’ project through online platform Open Source Malaria, said: “They’ve transformed starter material that’s worth pennies into something that has a real monetary value in the States.

“If you can obtain it cheaply in schools, then there’s no excuse for charging that much money for a drug. Especially from people that really need it and probably can’t afford to pay for it.”

However, Matthew Todd, an associate professor at the same university, who also mentored the students, said that they couldn’t sell the synthesized drug in the U.S. due to several complicated legal roadblocks.

“Turing has the exclusive rights to sell it, even though the drug is no longer under patent. To take the drug to market as a generic, you need to compare it to Turing’s product. If Turing won’t allow the comparisons to take place, you’d need to fund a whole new trial,” he explained.

Image via University of Sydney

Liked this? Then you’ll love these…

Fabric of the future: University researchers invent self-healing, toxin-neutralizing fabric

Dengue epidemic: Malaysian researchers invent ‘human-scented’ street light to trap mosquitoes